The Department of Agriculture released its annual liver fluke forecast on Tuesday, while AFBI released its version a few weeks ago with a similar risk predicted. Based on advice received from the liver fluke advisory group, it points to a high risk of infection across all parts of the country this winter.

This prediction is based on analysis of weather conditions and rainfall during the summer and autumn, and combining this with other information sources.

For sheep, blood samples were collected on 4,129 lambs entering abattoirs in September and October as part of a survey carried out by the Regional Veterinary Laboratories.

The samples were tested for antibodies to liver fluke to determine exposure levels.

As can be expected, preliminary data from the survey indicates the greatest exposure of lambs to liver fluke from counties on the western seaboard.

Beef HealthCheck

For cattle, data has been analysed from the Animal Health Ireland Beef HealthCheck programme.

It states: “Preliminary information indicates that nationally the frequency of fluke-damaged livers in cattle at slaughter has increased slightly over the summer months and into the autumn, with live fluke detected at low but consistent levels throughout this period.”

Similar to the case in sheep, the occurrence of liver fluke is greatest in cattle slaughtered from northwestern and western counties.

Variation

The Department advises farmers that significant variation can take place between and within individual farms, based on the soil type (heavy or free-draining) and the volume of rainfall received.

The mud snail, which is the intermediate host of the parasite that is required to complete its life cycle, is generally located in wetter acidic soils, with areas of fields with rushes a particularly common haven for mud snails to be found. Additionally, the forecast advises farmers to make use of historical farm information.

Treatment and control

Where a high risk is feared, the report advises farmers to consult with their vet to put a robust health programme in place.

“In using flukicides to control and treat liver fluke infection, particular attention should be given to dosing cattle at the time of housing, and sheep in autumn or earlier in the year if there are concerns based on faecal examination or prior history,” it states.

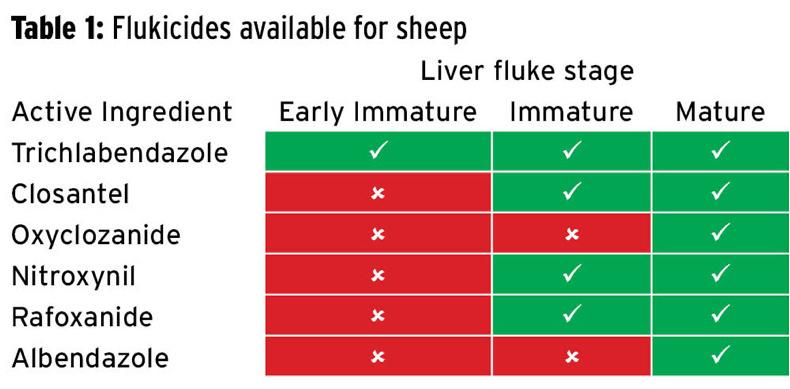

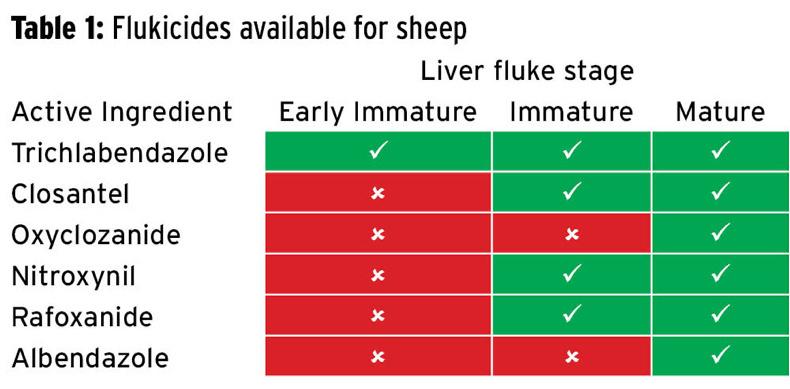

Looking closer at this recommendation for sheep, it is advised to use a flukicide that is effective against early immature as well as immature and mature flukes to protect against acute disease, which is the greatest concern at present. It also states that sheep should be removed from pasture to prevent reinfection.

Table 1 details flukicides on the market and the stage of live fluke each treats.

Previous fluke forecasts have advised treating outwintered flocks in November, January and April, with farms experiencing a very high threat advised to treat animals every four to six weeks and where possible staying clear from grazing high-risk areas. Remember also to alternate between products.

For cattle, the report advises that where the flukicide administered to cattle at housing is not effective against early immature fluke, “then faecal samples should be taken six to eight weeks after housing and tested for the presence of liver fluke eggs. This will determine whether a follow-up flukicide treatment is necessary.”

The report advises that this approach of testing faecal egg samples for the presence of liver fluke is important in determining the need for treatment, which will also help to reduce the rate of resistance developing to flukicides.

Sheep farmers should take note that faecal testing is not a reliable indicator of the presence of acute liver fluke. Therefore, all other available avenues of information should be utilised, such as following up on the health status of animals submitted for slaughter and submitting any unobvious deaths in animals for post-mortem examination.

Rumen fluke

Rumen fluke has increased in frequency in recent years, with the parasite sharing the same intermediate host to liver fluke.

Regarding the need to treat animals, the report advises: “If clinical signs such as rapid weight loss or diarrhoea are seen, or if there is a history of previous disease from rumen fluke on the farm, consult with your veterinary adviser as to whether treatment for rumen fluke is required. The finding of rumen fluke eggs in faecal samples of animals that are thriving and producing well is not reason enough to warrant treatment of these animals for rumen fluke.”

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: