Irish exports to Britain are about to face their greatest challenge in half a century as from 1 January we will no longer share the same single market or customs union. That means a return to export documentation including customs declarations and veterinary certification for products of animal origin and possible inspections at the port of entry.

All of this increases administration costs and has also the potential to disrupt the finely honed just-in-time delivery process that is operated by all large volume users of fresh agri-food produce.

There is also the added risk of tariffs of up to €1.5bn on Ireland’s €4.5bn of exports to Britain if the EU and UK don’t agree a no-tariffs, no-quotas trade deal to replace the UK membership of the customs union and single market.

At that point, it may be tempting to give up on the UK as a market for Irish agri-food exports. However, in a recent Irish Farmers Journal webinar, Minister for Foreign Affairs Simon Coveney refused to countenance that notion, and was strongly of the view that we must defend the place of Irish food produce on British shelves. He also correctly identified that it is simply impractical to suggest that Irish exporters can flick a switch and redirect exports to other markets overnight.

If there is no deal, Irish beef imports will immediately become very expensive in Britain and with a deal there will be an increased cost of doing business, estimated by farm business consultants Andersons, in a recent Irish Farmers Journal webinar, at approximately 11c/kg.

The other challenge that Irish imports in the UK are likely to face soon is competition from Australia and New Zealand as the UK is actively pursuing trade deals with them. That will make New Zealand a very competitive alternative option for dairy, beef and to a lesser extent sheepmeat, while Australia would be competitive in beef and sheepmeat, as unlike New Zealand it does not have a meaningful quota for exporting to the EU and UK.

Irish response

Irrespective of what trading arrangement is in place on 1 January 2021, Irish exports will face greater competition in Britain and the challenge is how the Irish position can be defended. Promotion of Irish agri-food and drink is the responsibility of Bord Bia, and it has been preparing for this eventuality for the past four years. Padraig Brennan, Director of Sectors at Bord Bia explains how Ireland still has some advantages.

British market: what works in our favour?

1 Closeness: no major supplier to Britain is closer geographically and despite whatever disruption occurs with the new trading arrangement, that will remain after 1 January. This will keep Ireland in the best position to be part of a just-in-time supply chain for fresh produce, as we have been for several years, and no potential supplier from the southern hemisphere can offer that flexibility.

2

Culture: this physical closeness also means that Britain and Ireland share a very similar culture with a common language, media and sporting interests. Bord Bia has been tracking British consumer sentiment towards Irish food and drink in the UK since January 2019 through its Brexit Consumer Pulse research. The research reveals an ongoing strong positive sentiment from British consumers as they perceive Irish meat and dairy products to be local with nearly nine in 10 saying they would purchase Irish beef with similar figures for Irish cheddar. This high propensity to purchase Irish beef is aligned just behind the scores achieved for both Scottish and English beef, which demonstrates how Irish beef is considered part of “local” supply.

3

Similar systems: Ireland has a similar production and farming system, particularly in livestock farming as Britain. We have a Quality Assurance (QA) scheme, which is recognised as equivalent to the UK Red Tractor scheme. Of course, other potential global suppliers can develop QA schemes but there is an advantage in one already in place.

Recent months have seen significant media coverage in the UK around the food standards of potential new suppliers to the British market from 2021 with concerns that some suppliers may not have the same standards as the UK in relation to traceability, animal welfare and the environmental impact potential. This has led to the NFU proposing a petition on future food standards which achieved over one million signatures.

Irish meat and dairy is in a position to positively navigate this trend due to the high standards of Irish agriculture thanks to 25 years of farm assurance and an understanding of these high standards from UK trade customers. However, it is important that we continue to further promote the high standards of Irish agriculture and look for alternative ways to differentiate Irish beef from other imports in the market.

4

Relationships: Ireland has been a supplier of agri-food to Britain for centuries and, in recent decades, many parts of the agri-food processing sector operate in both Britain and Ireland. A major UK supermarket group sitting down with its supplier to discuss a beef promotion is likely to find that supplier offering a mix of both Red Tractor UK beef and Bord Bia QA Irish beef. The strength of these relationships puts Ireland in a strong position to defend against external suppliers.

Key points

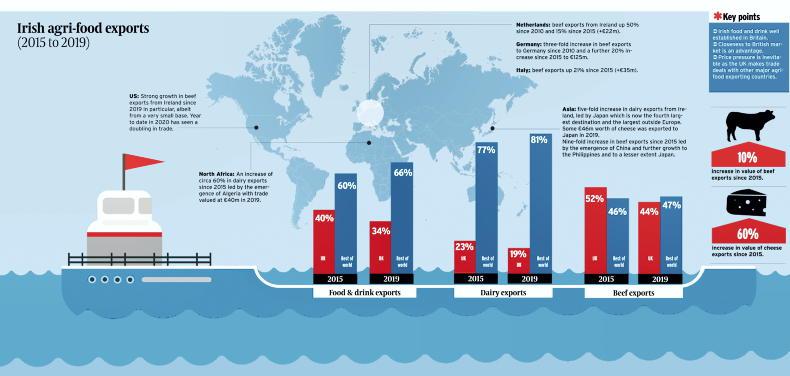

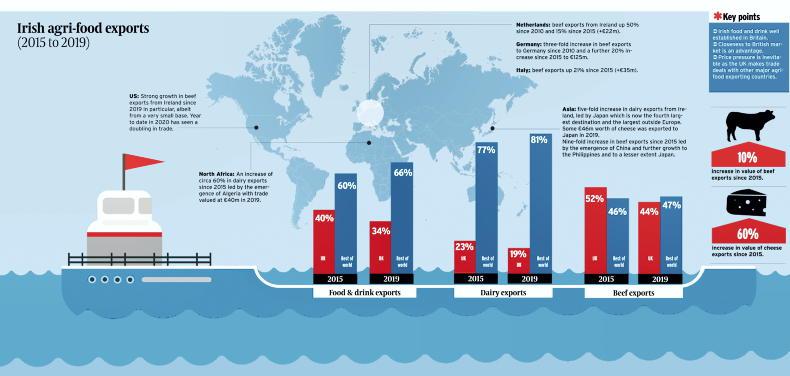

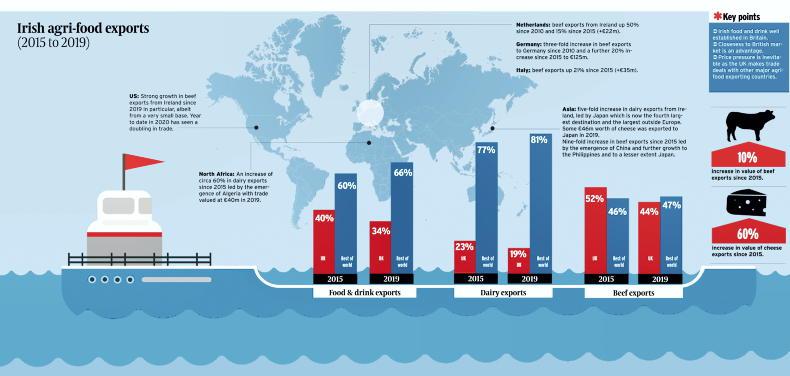

Irish food and drink well established in Britain.Closeness to British market is an advantage.Price pressure is inevitable as the UK makes trade deals with other major agri-food exporting countries.Competition: facing the challenges ahead

The most immediate challenge is likely to come from New Zealand and Australia. New Zealand beef is competitive at present, trading around the equivalent of €3.10/kg. Australia is much less so because of reduced supply due to restocking after a prolonged period of drought. Its current farmgate price is the equivalent of €4.02/kg for MSA grading steers, well ahead of Irish prices.

Ireland competes globally with New Zealand on dairy, so that should be manageable, and as New Zealand has not filled its quota of sheepmeat to the EU in recent years and it has an opposite season for lamb, we have a chance of being OK there too. Australia is not a large dairy exporter but it will have an interest in developing a lamb market in the UK as it has not had a meaningful quota unlike New Zealand.

Brazil and Argentina have in recent years had the cheapest cattle available, very much driven by a weak currency in the case of Brazil and a collapsing currency in the case of Argentina.

Their price this year has been in the region of €2.50/kg or less and poses a real threat to Irish beef.

Again, they are not significant dairy or sheepmeat exporters but Brazil in particular is a huge global exporter of both poultry and pigmeat. Overall, it is the Irish meat sector that is most exposed to global competition.

The US has been identified as a likely competitor but a trade deal between the US and UK isn’t a foregone conclusion and there remains the issue of standards on use of hormones in beef and chlorine in the washing process to be addressed. In any case, its farmgate price on beef is often on par with Ireland in recent years though it is particularly competitive on pigmeat.

Huge challenge

Notwithstanding these advantages that Ireland has, the reality is that our position as the preferred supplier of imported beef will be challenged after 1 January. Our share of British beef imports never drops below 70% and in 2020 it is running at 80%.

Meanwhile, Irish cheddar accounts for 90% of their cheddar imports so far this year and 60% of butter imports.

The plan

Bord Bia is focused on defending Ireland’s food and drink position on UK shelves and has already been active in the trade press with consumer advertising ahead of 1 January and this will be increased further throughout next year.

As well as working at trade level, Bord Bia will increase its engagement with consumers through advertising to reinforce already high awareness of the quality and reliability offered by Irish produce. A successful PGI application for beef would be a considerable asset in building a strong consumer campaign. British consumers are already familiar with PGIs in beef and lamb. Scotland and Wales have had them for 15 years and West Country Beef and Lamb from the southwest of England has had a PGI since 2014.

If Ireland secures a PGI, it enables Bord Bia to more forcefully promote the Irish in our grass-fed beef range and also enables us pitch for EU funding to finance an enhanced campaign.

Alongside all of this, Bord Bia will continue to develop other international markets inside and outside the EU as we have successfully done over the past decade. However, these will be to complement, and be an alternative, to the UK market, not to replace it.

Irish exports to Britain are about to face their greatest challenge in half a century as from 1 January we will no longer share the same single market or customs union. That means a return to export documentation including customs declarations and veterinary certification for products of animal origin and possible inspections at the port of entry.

All of this increases administration costs and has also the potential to disrupt the finely honed just-in-time delivery process that is operated by all large volume users of fresh agri-food produce.

There is also the added risk of tariffs of up to €1.5bn on Ireland’s €4.5bn of exports to Britain if the EU and UK don’t agree a no-tariffs, no-quotas trade deal to replace the UK membership of the customs union and single market.

At that point, it may be tempting to give up on the UK as a market for Irish agri-food exports. However, in a recent Irish Farmers Journal webinar, Minister for Foreign Affairs Simon Coveney refused to countenance that notion, and was strongly of the view that we must defend the place of Irish food produce on British shelves. He also correctly identified that it is simply impractical to suggest that Irish exporters can flick a switch and redirect exports to other markets overnight.

If there is no deal, Irish beef imports will immediately become very expensive in Britain and with a deal there will be an increased cost of doing business, estimated by farm business consultants Andersons, in a recent Irish Farmers Journal webinar, at approximately 11c/kg.

The other challenge that Irish imports in the UK are likely to face soon is competition from Australia and New Zealand as the UK is actively pursuing trade deals with them. That will make New Zealand a very competitive alternative option for dairy, beef and to a lesser extent sheepmeat, while Australia would be competitive in beef and sheepmeat, as unlike New Zealand it does not have a meaningful quota for exporting to the EU and UK.

Irish response

Irrespective of what trading arrangement is in place on 1 January 2021, Irish exports will face greater competition in Britain and the challenge is how the Irish position can be defended. Promotion of Irish agri-food and drink is the responsibility of Bord Bia, and it has been preparing for this eventuality for the past four years. Padraig Brennan, Director of Sectors at Bord Bia explains how Ireland still has some advantages.

British market: what works in our favour?

1 Closeness: no major supplier to Britain is closer geographically and despite whatever disruption occurs with the new trading arrangement, that will remain after 1 January. This will keep Ireland in the best position to be part of a just-in-time supply chain for fresh produce, as we have been for several years, and no potential supplier from the southern hemisphere can offer that flexibility.

2

Culture: this physical closeness also means that Britain and Ireland share a very similar culture with a common language, media and sporting interests. Bord Bia has been tracking British consumer sentiment towards Irish food and drink in the UK since January 2019 through its Brexit Consumer Pulse research. The research reveals an ongoing strong positive sentiment from British consumers as they perceive Irish meat and dairy products to be local with nearly nine in 10 saying they would purchase Irish beef with similar figures for Irish cheddar. This high propensity to purchase Irish beef is aligned just behind the scores achieved for both Scottish and English beef, which demonstrates how Irish beef is considered part of “local” supply.

3

Similar systems: Ireland has a similar production and farming system, particularly in livestock farming as Britain. We have a Quality Assurance (QA) scheme, which is recognised as equivalent to the UK Red Tractor scheme. Of course, other potential global suppliers can develop QA schemes but there is an advantage in one already in place.

Recent months have seen significant media coverage in the UK around the food standards of potential new suppliers to the British market from 2021 with concerns that some suppliers may not have the same standards as the UK in relation to traceability, animal welfare and the environmental impact potential. This has led to the NFU proposing a petition on future food standards which achieved over one million signatures.

Irish meat and dairy is in a position to positively navigate this trend due to the high standards of Irish agriculture thanks to 25 years of farm assurance and an understanding of these high standards from UK trade customers. However, it is important that we continue to further promote the high standards of Irish agriculture and look for alternative ways to differentiate Irish beef from other imports in the market.

4

Relationships: Ireland has been a supplier of agri-food to Britain for centuries and, in recent decades, many parts of the agri-food processing sector operate in both Britain and Ireland. A major UK supermarket group sitting down with its supplier to discuss a beef promotion is likely to find that supplier offering a mix of both Red Tractor UK beef and Bord Bia QA Irish beef. The strength of these relationships puts Ireland in a strong position to defend against external suppliers.

Key points

Irish food and drink well established in Britain.Closeness to British market is an advantage.Price pressure is inevitable as the UK makes trade deals with other major agri-food exporting countries.Competition: facing the challenges ahead

The most immediate challenge is likely to come from New Zealand and Australia. New Zealand beef is competitive at present, trading around the equivalent of €3.10/kg. Australia is much less so because of reduced supply due to restocking after a prolonged period of drought. Its current farmgate price is the equivalent of €4.02/kg for MSA grading steers, well ahead of Irish prices.

Ireland competes globally with New Zealand on dairy, so that should be manageable, and as New Zealand has not filled its quota of sheepmeat to the EU in recent years and it has an opposite season for lamb, we have a chance of being OK there too. Australia is not a large dairy exporter but it will have an interest in developing a lamb market in the UK as it has not had a meaningful quota unlike New Zealand.

Brazil and Argentina have in recent years had the cheapest cattle available, very much driven by a weak currency in the case of Brazil and a collapsing currency in the case of Argentina.

Their price this year has been in the region of €2.50/kg or less and poses a real threat to Irish beef.

Again, they are not significant dairy or sheepmeat exporters but Brazil in particular is a huge global exporter of both poultry and pigmeat. Overall, it is the Irish meat sector that is most exposed to global competition.

The US has been identified as a likely competitor but a trade deal between the US and UK isn’t a foregone conclusion and there remains the issue of standards on use of hormones in beef and chlorine in the washing process to be addressed. In any case, its farmgate price on beef is often on par with Ireland in recent years though it is particularly competitive on pigmeat.

Huge challenge

Notwithstanding these advantages that Ireland has, the reality is that our position as the preferred supplier of imported beef will be challenged after 1 January. Our share of British beef imports never drops below 70% and in 2020 it is running at 80%.

Meanwhile, Irish cheddar accounts for 90% of their cheddar imports so far this year and 60% of butter imports.

The plan

Bord Bia is focused on defending Ireland’s food and drink position on UK shelves and has already been active in the trade press with consumer advertising ahead of 1 January and this will be increased further throughout next year.

As well as working at trade level, Bord Bia will increase its engagement with consumers through advertising to reinforce already high awareness of the quality and reliability offered by Irish produce. A successful PGI application for beef would be a considerable asset in building a strong consumer campaign. British consumers are already familiar with PGIs in beef and lamb. Scotland and Wales have had them for 15 years and West Country Beef and Lamb from the southwest of England has had a PGI since 2014.

If Ireland secures a PGI, it enables Bord Bia to more forcefully promote the Irish in our grass-fed beef range and also enables us pitch for EU funding to finance an enhanced campaign.

Alongside all of this, Bord Bia will continue to develop other international markets inside and outside the EU as we have successfully done over the past decade. However, these will be to complement, and be an alternative, to the UK market, not to replace it.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article