There was no doubt that the shadow of Brexit loomed over Cereals 2017. The show took place less than a week after the UK general election and many realised that a proportion of the crops to be harvested in 2018 (sown this autumn) will be marketed in a post-Brexit world.

So attendees were eager to set out the priorities of the sector for the new government.

The critical importance of having some form of trade deal in place between the UK and the EU was highlighted by various speakers throughout the two days. At farm level, the message was clear. Whether one was farming 2,000ha in Lincolnshire or 200ha in Limavady, growers needed to Brexit-proof their business.

Brexit-proofing

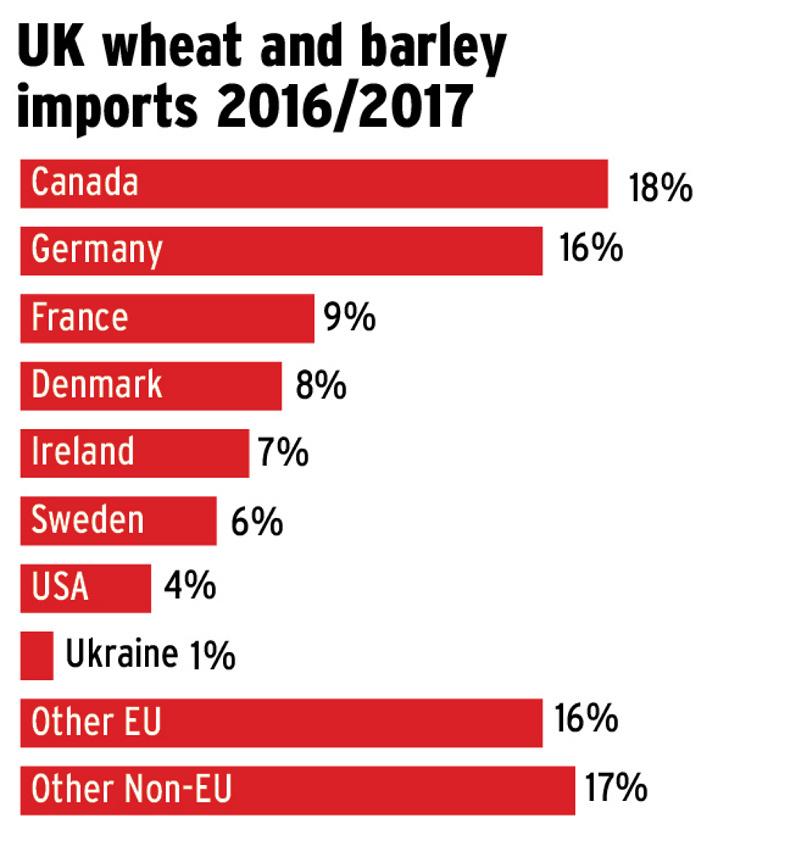

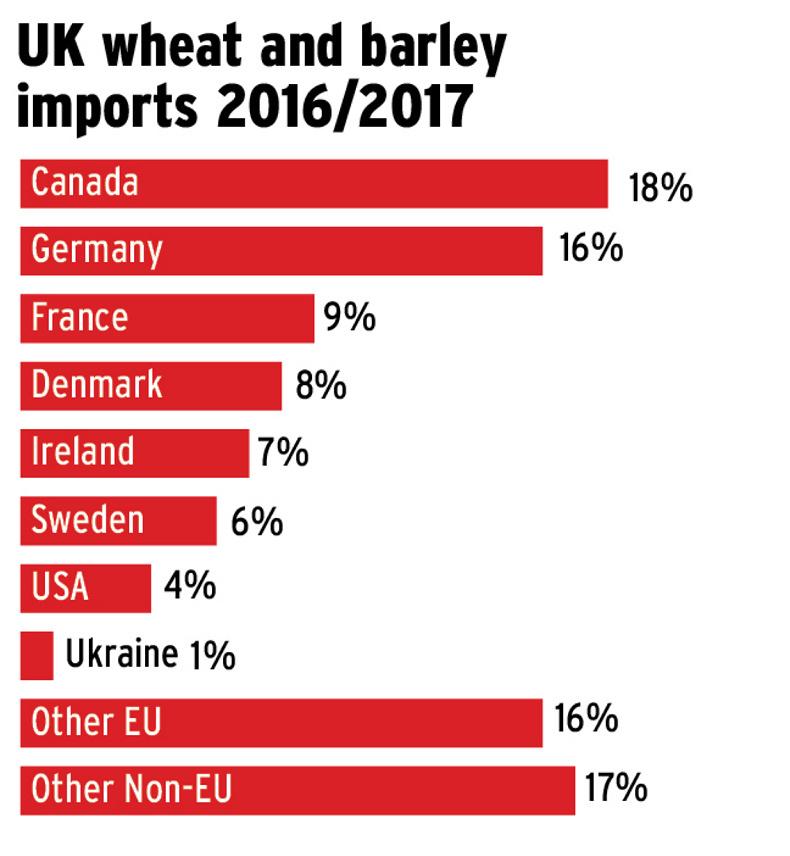

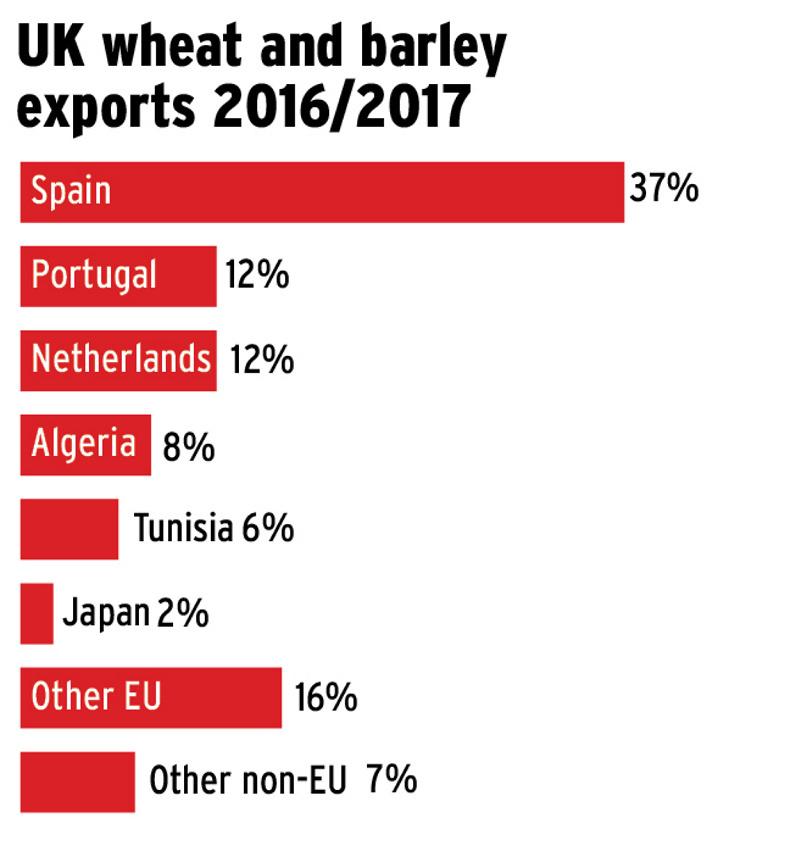

The UK typically produces a surplus of grain with the vast majority being exported to the EU (see graph). For example, in 2016 the UK exported 2.8m tonnes of wheat and over 80% of this went to EU countries; 66% of the 2m tonnes of exported barley also went to EU countries, along with 94% of the 430,000t of exported rapeseed. Around 70% of the wheat and barley imported into the UK (see graph) also came from EU countries, while around two-thirds of imported maize also originated from within the EU.

This complex interdependent trading relationship was highlighted in AHDB’s (Agricultural & Horticultural Development Board) new Horizon report, Post-Brexit Prospects for UK Grains, which was launched at Cereals 2017. The report states that due to the UK being a relatively small-scale exporter and high-cost producer, competing on the global grain market is likely to be difficult. This is essentially a numbers game driven by high volume and low margins.

The report also outlines a scenario where tougher trading conditions and reduced farm supports could put a question mark over arable production in marginal areas and eventually lead to a change in land use between agricultural sectors. With the UK outside of the EU and so potentially beyond the protectionism approach to GM imports, the UK could become a target for maize exports from the Americas.

The view of Tim Isaac, AHDB head of knowledge exchange (cereals and oilseeds), was that Brexit will bring both opportunities and threats for the UK arable sector. “While the UK arable sector will most likely be one of the least affected sectors, the threat of cuts to farm supports, reduced market access and a worst-case ‘cliff-edge’ Brexit scenario, means that growers should be preparing for Brexit.”

Tim advised growers to actively Brexit-proof their business through improving competitiveness, driving productivity, ensuring that businesses in the supply chain don’t exist in isolation, improving consistency of grain quality and getting to grips with potential grain and product niches at home and abroad.

“There will also be opportunities presented by Brexit and farmers are beginning to understand this,” he said. “We can explore new markets and there’s even potential for producers to expand their businesses. If there is a reduction in subsidies, this could actually help improve availability of land.”

Arable conferences

The arable conferences featured debates, panel sessions and seminars on a vast array of topics affecting both the UK and global arable sector. The panel session on Brexit discussed what might be in store as 2020 draws closer. The panel consisted of Meurig Raymond, National Farmers Union president; David Caffall, chief executive of the Agricultural Industries Confederation; Ruth Bailey, CEO of the Agricultural Engineers Association; Sir Peter Kendall, AHDB chair; and Paul Temple, AHDB chair (cereals and oilseeds).

There was unanimous agreement that a post-Brexit trade deal was needed which would not disadvantage UK farmers. While they all recognised the potential opportunities Brexit presents to the sector, the uncertainties surrounding their departure from the EU have already affected the sector.

Meurig said that if a trade deal is not struck, the Government will have to commit significant funds towards agriculture. “For me, the trade deal is the most important issue. If we end up with a fair trade deal we can look forward in an optimistic manner to an ambitious agricultural policy. But if we get a bad deal, the argument will be that we will need a good degree of financial support.”

David Caffall, AIC, said the effects of continued financial uncertainty created by Brexit have already forced some of the organisation’s members, which comprise mainly UK agricultural input suppliers, to delay or cancel important investment decisions.

Ruth Bailey, AEA, represents the UK farm machinery and components sector, worth over £4bn, and she stated that 60% of the sector’s exports go to the EU market, while 75% of its imports arrive from Europe. She stressed the need for a smooth policy which minimises the effects of leaving the single currency and customs union. “So we are looking for a smooth trading policy and as soft a Brexit as is possible. But there is an opportunity to become a highly efficient and highly productive leader in technology.”

UK growers’ thoughts

Shortly after one of the conferences I spoke with two Lincolnshire growers and asked them about their feelings and attitudes towards Brexit. While they didn’t tell me which way they had voted in last year’s referendum, they did state unequivocally that the uncertainties surrounding Brexit were worrying for their businesses.

The growers were very aware of the potential negative aspects which Brexit could impose on them. The potential cut in farm subsidies for UK producers was an obvious concern. They were also quite concerned about the availability of labour.

The situation demands that there needs to be joined-up thinking between government, farmers, businesses and everyone else along the supply chains. But this is not happening according to these growers and a feeling of powerlessness is prevalent.

SHARING OPTIONS