Did anyone believe that the United Kingdom would really vote to leave the EU? The reaction of those championing the Leave campaign on Friday morning merely reinforced the view that this was a referendum where many people voted out without thinking about the consequences. Clearly, the global financial markets were caught off guard. The shock result wiped almost $3 trillion off global shares with losses on the morning of the result exceeding those recorded during the darkest days of the US banking crisis in 2008.

While clarity has been at a premium over the past few days, Brexit has served to reinforce just how closely linked the economic fortunes of Ireland are with those of the UK. In this regard, the cautious and measured approach taken by the Irish Government is sensible.

There is little to be gained from trying to force the hand of the UK into invoking Article 50 of the Lisbon treaty. Whether inside or out of the EU, the UK is going to remain a vital trading partner with all 27 member states – none more so than Ireland – and will retain a powerful influence on the global stage.

Of course, at this stage we should not rule out the UK remaining part of the EU. Yes, it would require a second referendum – and I note the comments made by German chancellor Angela Merkel on Tuesday night that there is no way back.

But we are at the very early stages of negotiations and, in some ways, the ground has already been laid for such a move: in 1992, when the Danes voted to reject the Maastricht treaty; and in 2001 and 2008, when Ireland voted to reject the Nice and Lisbon treaties.

In all cases, a second referendum was held following increased concessions from EU members – some media reports suggest that this was part of the Boris Johnson’s strategy. Increased concessions around migration with the introduction of a ceiling on the movement of people would certainly give a newly elected government and prime minister a mandate to go back to the people.

Nevertheless, despite the desirability and logic of such an outcome, Ireland cannot afford to adopt a hope-for-the-best policy. At this point, we have little option but to hope for the best and plan for the worst.

Short-term challenges

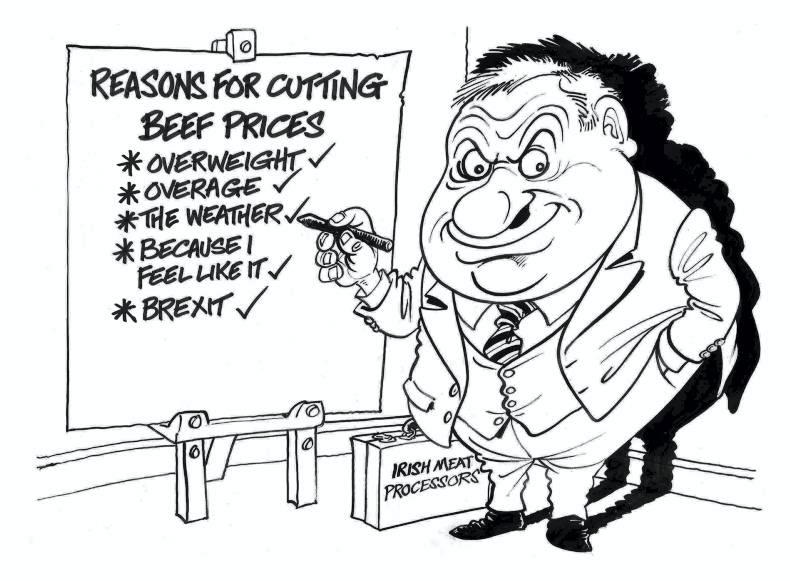

We are already seeing the short-term challenges that are created by uncertainty in the market in the form of currency volatility. In the beef sector, we have seen some opportunistic buying by processors. However, from a farmer’s perspective, there is a need for calm. The reality is that while the euro has increased in value from 76p to a high of 83p, such swings have been commonplace in recent years. In 2009, the euro reached a high of 95p and remained above 85p for four of the preceding five years. Large agri food businesses with exposure clearly have hedging mechanisms in place.

In many ways, the 9% increase in the euro against sterling in the wake of Brexit is a long way short of what many analysts had feared. The 15% swings that some had forecast have been revised on the realisation that Brexit is equally as damaging to both the EU and UK economies.

Trade

From an agricultural perspective, the real challenges created by Brexit are centred around trade. Here we detail just how reliant our agri food industry is on the UK market. With such reliance on the British consumer, the fortunes of Irish farmers are heavily exposed to even the slightest disruption to the normal flow of goods, changes in market demand or a shift in the competitor portfolio. Unfortunately, Brexit creates the ideal environment for all three: increased border controls with the potential for import tariffs; a recession leading to reduced consumer spending power; and preferential trading arrangements with non-EU competitors. The latter is without doubt the most concerning.

In keeping in line with the UK’s deep-rooted cheap food policy, there is a real risk that policymakers will look west as a means of bridging the gap between demand for key commodities and domestic production.

Unfortunately from an Irish perspective, the gaze west will extend beyond our shores with a much more intense interest in forming a strategic trade partnership with the Mercosur bloc, including the agricultural powerhouses of Brazil, Argentina and the US. While we have seen beef taken off the negotiating table in EU-Mercosur trade talks for now, there is no doubt that it will take centre stage in any UK-Mercosur negotiations. British politicians are not going to sacrifice access to the Brazilian, Argentinian and US markets to protect their farmers.

Preferential access

Much of the discussion to date has been around Ireland securing preferential access to the UK market. While likely to be challenged, even if this were to happen, it would be no silver bullet for our agri food sector. UK trade deals outside of the EU could leave Irish exports fighting for space in a UK market with competitors from South America, New Zealand and the US – competitors that have preferential market access without the compliance and regulatory costs associated with EU production standards. For example, should the UK lift the ban on the use of growth hormones or allow market access to US hormone-treated beef, the EU ban on such practices would place Ireland at an immediate €150-€250 per finished animal disadvantage.

So, how should we respond? At a political level, the potential impact of Brexit on rural Ireland needs to be put centre stage. Few have probably grasped the enormity of what lies ahead, instead focusing on the day-to-day of market prices. This has to change. And quickly. The clock is now ticking and there could be as little as 24 months on the timer.

Ireland needs to play tough with Europe. In recent days, we have seen a staunch defence of Ireland’s corporation tax rate with senior members of the Fine Gael party issuing red-line warnings. We expect a similar approach to be taken in defence of Ireland’s agri food interests.

A commitment must be secured from the EU that it will provide support to Ireland in helping reorientate the focus of food exports. This support should include:

A commitment to provide direct market intervention should prices collapse in response to a UK-Mercosur trade deal. The introduction of temporary export refunds to help develop non-EU markets for Irish exports. Flexibility on future CAP payments to allow member states link payments back to supporting active food producers and security around future budgets. Aligned to this, the Irish Government must explore all market opportunities that exist for Irish food exports. In recent years, the opening of the US and Chinese markets have been subject to great political fanfare. While we see Brazilian beef flooding into China, Ireland remains on the sidelines. Serious political work now needs to go into developing these markets to their potential.

At the same time, we should not lose sight of the importance of building ever-stronger relationships with the British consumer.

From a marketing perspective, Bord Bia has always treated the UK as a safe haven where exports remained largely steady. This is clearly no longer the case and our marketing strategy must change to reflect this. Our inability to form a strong Irish food brand in the UK could prove costly in what is set to become a much more challenging environment.

Convincing British farmers

Meanwhile, at farm politics level, the real challenge is to convince British farmers that they are in a much stronger position if imported product is sourced from a near neighbour with a similar cost production system rather than to have their markets flooded with cheap imports of beef, pigmeat, lamb and dairy. This may in fact become an easier sell when British farmers realise just how big a gamble they have taken with Brexit and as the deep-rooted commitment to a cheap food policy within the corridors of Westminster comes to the fore.

While much of the focus in recent days has been on the immediate challenges facing farmers, the reality is that nothing has changed. There is no need for a panic reaction. However, in the longer term, we should be under no illusions: Brexit presents one of the biggest threats in a generation to the future prosperity of Irish agriculture and indeed rural Ireland. In time, British farmers will also realise the extent of their exposure. While we hope that common sense will prevail, Ireland needs to prepare for what could be a ticking time bomb for our agri food sector.

Did anyone believe that the United Kingdom would really vote to leave the EU? The reaction of those championing the Leave campaign on Friday morning merely reinforced the view that this was a referendum where many people voted out without thinking about the consequences. Clearly, the global financial markets were caught off guard. The shock result wiped almost $3 trillion off global shares with losses on the morning of the result exceeding those recorded during the darkest days of the US banking crisis in 2008.

While clarity has been at a premium over the past few days, Brexit has served to reinforce just how closely linked the economic fortunes of Ireland are with those of the UK. In this regard, the cautious and measured approach taken by the Irish Government is sensible.

There is little to be gained from trying to force the hand of the UK into invoking Article 50 of the Lisbon treaty. Whether inside or out of the EU, the UK is going to remain a vital trading partner with all 27 member states – none more so than Ireland – and will retain a powerful influence on the global stage.

Of course, at this stage we should not rule out the UK remaining part of the EU. Yes, it would require a second referendum – and I note the comments made by German chancellor Angela Merkel on Tuesday night that there is no way back.

But we are at the very early stages of negotiations and, in some ways, the ground has already been laid for such a move: in 1992, when the Danes voted to reject the Maastricht treaty; and in 2001 and 2008, when Ireland voted to reject the Nice and Lisbon treaties.

In all cases, a second referendum was held following increased concessions from EU members – some media reports suggest that this was part of the Boris Johnson’s strategy. Increased concessions around migration with the introduction of a ceiling on the movement of people would certainly give a newly elected government and prime minister a mandate to go back to the people.

Nevertheless, despite the desirability and logic of such an outcome, Ireland cannot afford to adopt a hope-for-the-best policy. At this point, we have little option but to hope for the best and plan for the worst.

Short-term challenges

We are already seeing the short-term challenges that are created by uncertainty in the market in the form of currency volatility. In the beef sector, we have seen some opportunistic buying by processors. However, from a farmer’s perspective, there is a need for calm. The reality is that while the euro has increased in value from 76p to a high of 83p, such swings have been commonplace in recent years. In 2009, the euro reached a high of 95p and remained above 85p for four of the preceding five years. Large agri food businesses with exposure clearly have hedging mechanisms in place.

In many ways, the 9% increase in the euro against sterling in the wake of Brexit is a long way short of what many analysts had feared. The 15% swings that some had forecast have been revised on the realisation that Brexit is equally as damaging to both the EU and UK economies.

Trade

From an agricultural perspective, the real challenges created by Brexit are centred around trade. Here we detail just how reliant our agri food industry is on the UK market. With such reliance on the British consumer, the fortunes of Irish farmers are heavily exposed to even the slightest disruption to the normal flow of goods, changes in market demand or a shift in the competitor portfolio. Unfortunately, Brexit creates the ideal environment for all three: increased border controls with the potential for import tariffs; a recession leading to reduced consumer spending power; and preferential trading arrangements with non-EU competitors. The latter is without doubt the most concerning.

In keeping in line with the UK’s deep-rooted cheap food policy, there is a real risk that policymakers will look west as a means of bridging the gap between demand for key commodities and domestic production.

Unfortunately from an Irish perspective, the gaze west will extend beyond our shores with a much more intense interest in forming a strategic trade partnership with the Mercosur bloc, including the agricultural powerhouses of Brazil, Argentina and the US. While we have seen beef taken off the negotiating table in EU-Mercosur trade talks for now, there is no doubt that it will take centre stage in any UK-Mercosur negotiations. British politicians are not going to sacrifice access to the Brazilian, Argentinian and US markets to protect their farmers.

Preferential access

Much of the discussion to date has been around Ireland securing preferential access to the UK market. While likely to be challenged, even if this were to happen, it would be no silver bullet for our agri food sector. UK trade deals outside of the EU could leave Irish exports fighting for space in a UK market with competitors from South America, New Zealand and the US – competitors that have preferential market access without the compliance and regulatory costs associated with EU production standards. For example, should the UK lift the ban on the use of growth hormones or allow market access to US hormone-treated beef, the EU ban on such practices would place Ireland at an immediate €150-€250 per finished animal disadvantage.

So, how should we respond? At a political level, the potential impact of Brexit on rural Ireland needs to be put centre stage. Few have probably grasped the enormity of what lies ahead, instead focusing on the day-to-day of market prices. This has to change. And quickly. The clock is now ticking and there could be as little as 24 months on the timer.

Ireland needs to play tough with Europe. In recent days, we have seen a staunch defence of Ireland’s corporation tax rate with senior members of the Fine Gael party issuing red-line warnings. We expect a similar approach to be taken in defence of Ireland’s agri food interests.

A commitment must be secured from the EU that it will provide support to Ireland in helping reorientate the focus of food exports. This support should include:

A commitment to provide direct market intervention should prices collapse in response to a UK-Mercosur trade deal. The introduction of temporary export refunds to help develop non-EU markets for Irish exports. Flexibility on future CAP payments to allow member states link payments back to supporting active food producers and security around future budgets. Aligned to this, the Irish Government must explore all market opportunities that exist for Irish food exports. In recent years, the opening of the US and Chinese markets have been subject to great political fanfare. While we see Brazilian beef flooding into China, Ireland remains on the sidelines. Serious political work now needs to go into developing these markets to their potential.

At the same time, we should not lose sight of the importance of building ever-stronger relationships with the British consumer.

From a marketing perspective, Bord Bia has always treated the UK as a safe haven where exports remained largely steady. This is clearly no longer the case and our marketing strategy must change to reflect this. Our inability to form a strong Irish food brand in the UK could prove costly in what is set to become a much more challenging environment.

Convincing British farmers

Meanwhile, at farm politics level, the real challenge is to convince British farmers that they are in a much stronger position if imported product is sourced from a near neighbour with a similar cost production system rather than to have their markets flooded with cheap imports of beef, pigmeat, lamb and dairy. This may in fact become an easier sell when British farmers realise just how big a gamble they have taken with Brexit and as the deep-rooted commitment to a cheap food policy within the corridors of Westminster comes to the fore.

While much of the focus in recent days has been on the immediate challenges facing farmers, the reality is that nothing has changed. There is no need for a panic reaction. However, in the longer term, we should be under no illusions: Brexit presents one of the biggest threats in a generation to the future prosperity of Irish agriculture and indeed rural Ireland. In time, British farmers will also realise the extent of their exposure. While we hope that common sense will prevail, Ireland needs to prepare for what could be a ticking time bomb for our agri food sector.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: