Digestion in itself is not rocket science. Insulate a tank, heat it up to over 20oC and you produce biogas, of which over 40% will be methane. However, when deciding on the viability of such an undertaking, the following criteria need to be given the utmost consideration.

You need a constant supply of fresh feed stock and the right feed type for animals.

Constant supply of fresh feed stock

On Irish farms, this would be slurry, fresh grass or energy crops such as maize.

Slurry can be extremely variable when it comes to energy production due to seasonality – the availability of fresh slurry throughout the year.

Animals tend to be housed for approximately four months of the year, so the remaining eight months can be a problem. This could be overcome if we were to consider feeding fresh grass to the digester. The grass would have to be macerated prior to feeding the digester, so an additional energy requirement to run such a machine needs to be accounted for and also you would have to evaluate issues such as the time required to undertake cutting and transporting, carbon footprint, etc.

Feed type fed to animals

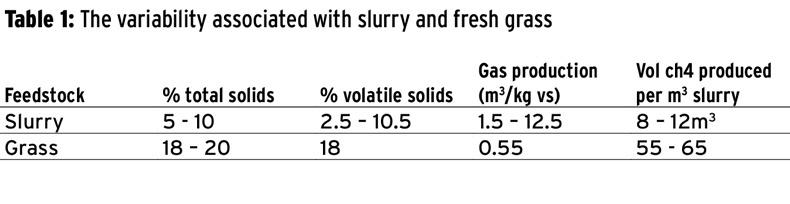

Rations with high protein content tend to contribute to a more rapid breakdown or degradation in the slurry and ammonia production in the digester, which would affect the pH of the digester – not good for gas production.Fibre content of the main diet would influence the retention time of the slurry in the digester. Table 1 demonstrates the variability associated with slurry and fresh grass.What to consider when building

a digester

Sizing the digester: as a rule of thumb, a digester will produce approximately 2.5 to three times its capacity in gas. Careful consideration must be given to availability of feedstock 365 days of the year. It would be necessary for such on-farm digesters to require additional feedstock such as waste food, dairy waste, belly grass, etc, to supplement the on-farm-produced feedstock .What to do with the gas produced: access to the grid can be expensive. Generally, it would require the installation of a CHP unit, which tends to be expensive to buy and has a high maintenance cost because the gas itself tends to have H2S and NH3 in it, which are extremely corrosive. Nobody ever talks about the cost of installing gas scrubbers to protect these CHPs. Sale of the gas to companies such as Calor requires the installation of a gas upgrading unit.Education: this is an area which tends to be given very little consideration when an individual is deciding on putting up a digester. It is strongly recommended that such a person gets hands-on experience working on an existing digester plant and attending specially arranged courses, ideally in Germany but also in the UK. It is indeed a complex business when dealing with gas production in large volumes.On-farm digestion in Ireland – is

there a future?

Certainly digestion can tick a lot of boxes when you look at its potential contribution towards carbon dioxide emissions. Remember, one unit of methane equals 25 carbon units.

The digestate tends to make nutrients more readily available (particularly N) when applied to land, due to the fact that it has been digested.

It is a good story all round, but, in my opinion, average farm sizes and stock numbers per farm here would have difficulty in sustaining both the running costs and capital expenditure of such an undertaking without gate fees for taking in other wastes. The electrical network throughout the country is inadequate to accommodate additional electrical supplies. The refit tariff is indeed nothing to shout about – circa 13c/kWh.

Not a total gloom and doom story

I would say that there is potential for Irish agriculture to contribute to emission reduction, but on a community basis. Consider the following: supposing that there was a centralised digester located near a town, village, with a number of farmers (co-ops) supplying slurry to it.

The heat produced here would be supplied to that community (district heating). Farmers would be paid via a percentage of the energy used in these households.

There is EU funding available per household to embrace something like this. Electrical energy produced at such a site could be sold to some local small industry. One transport truck (run on gas supplied from such a plant) would pick up and deliver the digestate back to the farms.

Such an undertaking would significantly reduce Co2 emissions on farms, reduce the amount of emissions from households, heated swimming pools, offices, factories, etc.

The versatility of such a plant would also be a great benefit because when heat demand is at its highest, more methane could be allocated to the gas burners and when less heat is required, methane could be redirected to electrical production. We need to be careful how we sell such a package to individuals.

It can be a very easy to show positive returns from a digester. Anyone can talk about the production of certain volumes of methane gas from various feedstocks and the energy returns from the same (Buswell Formula).

My advice when costing such a project is to discuss gas quality, the installation of gas scrubbers, labour requirement for a 365-day 24/7 job, automation and the costs associated with the CHP maintenance requirement.

Digestion has a role to play in Ireland but in a communal role, as mentioned, with both urban and rural working together to their mutual benefit.

With careful planning and strategic development, it is likely that this can be achieved.

Read more from our special focus on renewables

Ireland’s struggling renewables sector at a crossroads

Renewables: take tax and legal advice

Solar frenzy almost grinds to a halt

Digestion in itself is not rocket science. Insulate a tank, heat it up to over 20oC and you produce biogas, of which over 40% will be methane. However, when deciding on the viability of such an undertaking, the following criteria need to be given the utmost consideration.

You need a constant supply of fresh feed stock and the right feed type for animals.

Constant supply of fresh feed stock

On Irish farms, this would be slurry, fresh grass or energy crops such as maize.

Slurry can be extremely variable when it comes to energy production due to seasonality – the availability of fresh slurry throughout the year.

Animals tend to be housed for approximately four months of the year, so the remaining eight months can be a problem. This could be overcome if we were to consider feeding fresh grass to the digester. The grass would have to be macerated prior to feeding the digester, so an additional energy requirement to run such a machine needs to be accounted for and also you would have to evaluate issues such as the time required to undertake cutting and transporting, carbon footprint, etc.

Feed type fed to animals

Rations with high protein content tend to contribute to a more rapid breakdown or degradation in the slurry and ammonia production in the digester, which would affect the pH of the digester – not good for gas production.Fibre content of the main diet would influence the retention time of the slurry in the digester. Table 1 demonstrates the variability associated with slurry and fresh grass.What to consider when building

a digester

Sizing the digester: as a rule of thumb, a digester will produce approximately 2.5 to three times its capacity in gas. Careful consideration must be given to availability of feedstock 365 days of the year. It would be necessary for such on-farm digesters to require additional feedstock such as waste food, dairy waste, belly grass, etc, to supplement the on-farm-produced feedstock .What to do with the gas produced: access to the grid can be expensive. Generally, it would require the installation of a CHP unit, which tends to be expensive to buy and has a high maintenance cost because the gas itself tends to have H2S and NH3 in it, which are extremely corrosive. Nobody ever talks about the cost of installing gas scrubbers to protect these CHPs. Sale of the gas to companies such as Calor requires the installation of a gas upgrading unit.Education: this is an area which tends to be given very little consideration when an individual is deciding on putting up a digester. It is strongly recommended that such a person gets hands-on experience working on an existing digester plant and attending specially arranged courses, ideally in Germany but also in the UK. It is indeed a complex business when dealing with gas production in large volumes.On-farm digestion in Ireland – is

there a future?

Certainly digestion can tick a lot of boxes when you look at its potential contribution towards carbon dioxide emissions. Remember, one unit of methane equals 25 carbon units.

The digestate tends to make nutrients more readily available (particularly N) when applied to land, due to the fact that it has been digested.

It is a good story all round, but, in my opinion, average farm sizes and stock numbers per farm here would have difficulty in sustaining both the running costs and capital expenditure of such an undertaking without gate fees for taking in other wastes. The electrical network throughout the country is inadequate to accommodate additional electrical supplies. The refit tariff is indeed nothing to shout about – circa 13c/kWh.

Not a total gloom and doom story

I would say that there is potential for Irish agriculture to contribute to emission reduction, but on a community basis. Consider the following: supposing that there was a centralised digester located near a town, village, with a number of farmers (co-ops) supplying slurry to it.

The heat produced here would be supplied to that community (district heating). Farmers would be paid via a percentage of the energy used in these households.

There is EU funding available per household to embrace something like this. Electrical energy produced at such a site could be sold to some local small industry. One transport truck (run on gas supplied from such a plant) would pick up and deliver the digestate back to the farms.

Such an undertaking would significantly reduce Co2 emissions on farms, reduce the amount of emissions from households, heated swimming pools, offices, factories, etc.

The versatility of such a plant would also be a great benefit because when heat demand is at its highest, more methane could be allocated to the gas burners and when less heat is required, methane could be redirected to electrical production. We need to be careful how we sell such a package to individuals.

It can be a very easy to show positive returns from a digester. Anyone can talk about the production of certain volumes of methane gas from various feedstocks and the energy returns from the same (Buswell Formula).

My advice when costing such a project is to discuss gas quality, the installation of gas scrubbers, labour requirement for a 365-day 24/7 job, automation and the costs associated with the CHP maintenance requirement.

Digestion has a role to play in Ireland but in a communal role, as mentioned, with both urban and rural working together to their mutual benefit.

With careful planning and strategic development, it is likely that this can be achieved.

Read more from our special focus on renewables

Ireland’s struggling renewables sector at a crossroads

Renewables: take tax and legal advice

Solar frenzy almost grinds to a halt

SHARING OPTIONS