Supports withdrawn in last 10 years

The Irish suckler cow has seen support payments gradually reduced in the last 10 years.

While not directly hitting the suckler cow, scheme payment reductions, for example in the Areas of Natural Constraint scheme, directly affect suckler farmers on marginal land the most.

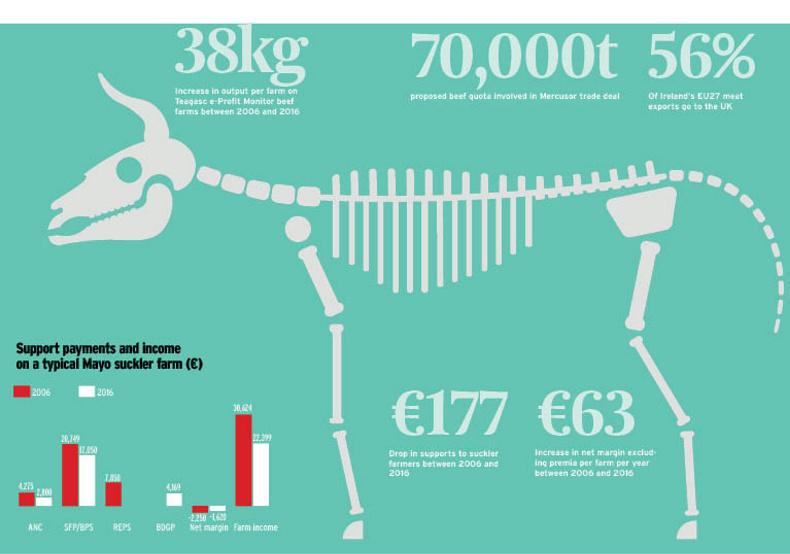

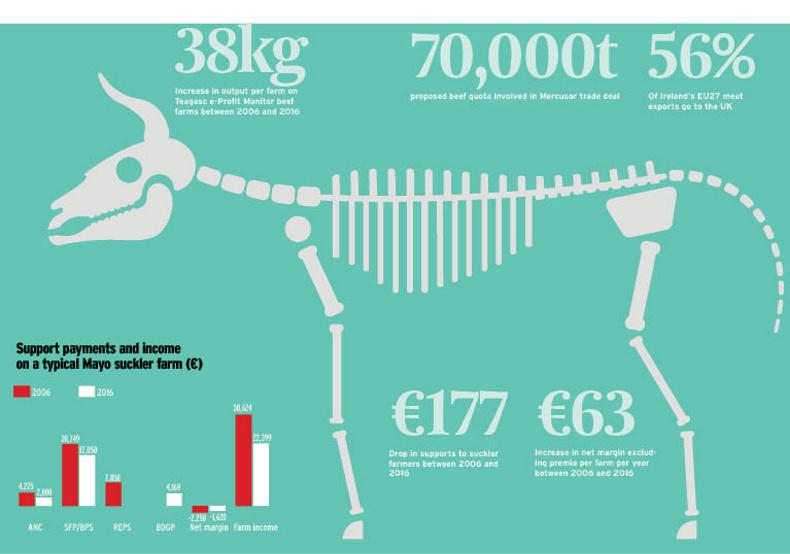

We have seen a reduction in support payments of €177/cow over the past 10 years which has been detrimental to the survival of the sector.

To look at this in detail, we took a look at a typical Co Mayo farm. Farm size is 45ha with 50 suckler cows, selling progeny as stores around 12 months of age. Stocking rate is 1.5 LU/ha. The farm is in BDGP but unable to get into GLAS. It was in REPS in the past. The graph below compares support payments in 2006 v 2016. Support payments in 2006 amounted to €32,874, while support payments in 2016 have dropped to €24,019, a drop of €8,855 or €177/cow on this 50-cow farm.

Bottom line

The cattle enterprise is contributing nothing to the bottom line and in 2016 the margin from the cattle enterprise ate into the support payments to the tune of €1,620.

This reduction in support for this struggling sector has meant margins have become tighter and in turn encouraging young people into the sector has become more difficult.

Many of our progressive young suckler farmers have moved to dairying in the east of the country while beef farms in the west find it hard to get a successor to carry on full-time farming and many have reduced stock numbers and gone part-time.

A €15,000 startup grant was available to young farmers who started farming in 2006.

This drain of youth is worrying as without young people fighting for a sector, it is greatly weakened. Young people have options.

It isn’t just a case of doing what was done on a farm. Hard figures will drive decision making in the future.

While the BDGP has helped on some farms, one has to ask the question is it directly targeted at those that need it most and why have more farmers not joined.

Brexit – the biggest threat in our lifetime

As we export 90% of what we produce, any disruptions in trade or increased tarriffs will have a huge effect on our industry. This could have huge knock-on effects for the EU beef market.

Currently Ireland exports 50% of its beef to the UK, 45% to other EU countries and 5% outside the EU.

Looking at a trade tarriff of 50% on top our beef price to get into the UK will mean our beef won’t be able to compete with other countries such as Brazil or Argentina.

A recent EU meat industry report says that the loss of trade with the UK is predicted to leave the EU considerably oversupplied with beef at 116% of consumption and that is before any further access to the EU market as a result of trade discussions.

The EU report predicts a drop in the market value of beef by 8% as a result of the loss of trade with the UK which is inevitable given an average tariff burden of 50% in the meat sector but as much as 100% in some categories.

The EU report also confirms that Ireland will be hardest hit as it exports more beef, pig meat and sheepmeat than all of the other EU26 countries combined.

Ireland currently supplies 56% of the EU27 meat exports to the UK and therefore the impact of Brexit will hit the Irish meat industry hardest of all.

Technical efficiency deficit

All of the blame cannot lie with the EU or national governments for the lack of support for the sector. In terms of technical progress, the sector has fallen behind where it needs to be.

Teagasc has said on numerous occasions that stocking rate and output are two of the main drivers of profitability on beef farms. In 2006, the stocking rate for 92 beef farms who completed a profit monitor in 2005 and 2006 was 1.82LU/ha.

In 2016, that stocking rate had risen to 1.86LU/ha. Output, a key driver of profitability, was 623kg/ha in 2006. This went to 661kg/ha in 2016, an improvement of 38kg over the 10-year period or 3.8kg per farm per year.

Bear in mind that these figures are taken from the top flight of beef farmers completing a profit monitor every year.

Calves per cow per year and calving interval, again key measures of technical efficiency, have bobbed around 0.85 calves per cow per year and 400-day interval for the past 10 years showing no real signs of progressive change.

We can blame genetics but management also has a huge role to play. I believe our aging demographic has stifled technology uptake but it’s a chicken and egg situation. If the profitability isn’t in the system, it’s hard to encourage new blood into it.

The market for the product

Unfortunately for suckler beef, some market issues tend to penalise the quality-bred animal. The first is the size of carcase.

The better the beef genetics in an animal, the bigger it is likely to grow. Large beef carcases mean large cuts which tend to get penalised in the market, particularly the steak meat.

For example, a loin from a 460kg U grade carcase could be worth up to €5/kg less in the wholesale market than a loin from a lesser quality O+ grading carcase weighing 360kg.

That alone could mean €100 on a beef carcase.

The additional issue is the increasing proportion of the carcase that is sold as mince in the retail sector or ground manufacturing beef, primarily for burgers in the food service sector and burger chains.

With this percentage of the carcase now heading towards 60%, it means the market opportunity is diminished as it doesn’t matter how plain the carcase is if it is heading for the mincer. Dairy beef ticks this box for the processor.

Mercusor

The current offer on the table to the four Mercosur nations includes an additional 70,000t preferential market access quota, involving a tariff rate of 7.5%. This includes 35,000t of fresh beef, made up of high-value Hilton beef and young grazing beef, plus 35,000t of frozen beef.

A 2016 proposal of 78,000t was withdrawn before being formally offered due to a huge outcry across several member states.

If this deal were to go through and Ireland was to lose its access to the UK, this would mean the already oversupplied EU beef market would be flooded with beef from countries within the EU and Mercosur beef.

This would have a serious negative knock-on effect on beef and cattle prices in Ireland, with processors having to turn to new emerging markets outside the EU to sell product.

These new markets will take years to develop and mature and it is questionable whether they will grow as fast as we need them to if a Mercosur trade deal is followed through on.

Opportunities

It would be easy to conclude from modern consumer trends in beef consumption that there is no place in the market for the specialist suckler beef production, particularly from larger suckler breeds.

It is too early to draw that conclusion but work has to be done to make the product market relevant and then promoted and marketed in a way that the consumer sees the added value of specialised beef production.

While there may be a problem at present, beef from breeds that were out of fashion is becoming fashionable again.

Twenty years ago, Hereford and Angus breeds were seen as a liability in the beef industry at a time when carcases couldn’t be big enough or lean enough. As this trend has diminished, traditional breeds have enjoyed a resurgence and now command a premium in the market.

New markets such as Japan are opening up and should offer real potential but we must be prepared for the long road with these emerging markets.

Conclusion

We can sit back and say the market can determine whether the suckler cow needs to survive. However, we need to be mindful of rural Ireland and its existence. A recent IFA study demonstrated that every €1 invested in suckler cow support contributed €4 to local economies.

The blame shouldn’t completely lie with support payments. Technology uptake on beef farms has been extremely low in the past 10 years.

An improvement in the net margin excluding premia of €63 per farm per year from 2006 to 2016 could hardly be called progress.

We have seen from programmes such as the Teagasc/Irish Farmers Journal BETTER farm programme that improvements can be made inside the farm gate and this can bring real change to the bottom line on many farms.

The Irish suckler cow is in for a tough few years ahead and her survival is on the line. It’s going to take a joint effort from farmers, industry and policy makers to ensure the Irish suckler remains on Irish pasture.

SHARING OPTIONS