In 2009, the EU adopted the Renewable Energy Directive (RED), which mandated for the first time that 10% of the transport fuel used by member states must come from biofuels by 2020. While oil companies were believed to be against it, the Renewable Energy Directive was just the opening Dublin businessman Mark Turley had been waiting for.

Mark Turley.

“I’d been looking at investing in renewables since 2007,” says Turley. “Most renewable energies need to be subsidised in order to make them work but ethanol was the exception.”

With the EU’s renewables directive in place, Turley and his team started a new business called Ethanol Europe and began construction in 2010 of a new biofuels plant. Located on the edge of the river Danube in Hungary, the plant required a capital investment of €150m, with construction completed in 2012, and had an initial capacity of 200m litres of ethanol per year.

Today, the plant in Hungary is pushing out 500m litres of ethanol a year, making Turley chief executive of Europe’s largest ethanol biorefinery with a 10% share of the 5bn litre market. Ethanol Europe takes in about 1.1m tonnes of maize corn every year, with about 60% sourced of this sourced directly from local farmers.

Abundant supplies

Turley says he chose Hungary as the location to build his ethanol plant because farmers grew abundant supplies of maize corn in the country but had little market for it. In the mid-2000s, Hungary accounted for 80% of all maize stocks offered into intervention at just €100/t.

Despite the electrical revolution taking hold in the car industry, Turley remains bullish on the long-term fundamentals of ethanol. Most large countries in Europe such as Germany and France already have 10% ethanol blended into their petrol fuels. However, Ireland and the UK still have just 5% ethanol in fuels.

By next year, both governments are expected to increase the ethanol mandate to 10% to meet targets under the EU’s renewables directive. Turley believes ethanol blends in Europe need to go as high as 25% to 30%, particularly as demand for liquid fuels in Europe is growing at 3% to 4% per annum.

Byproducts

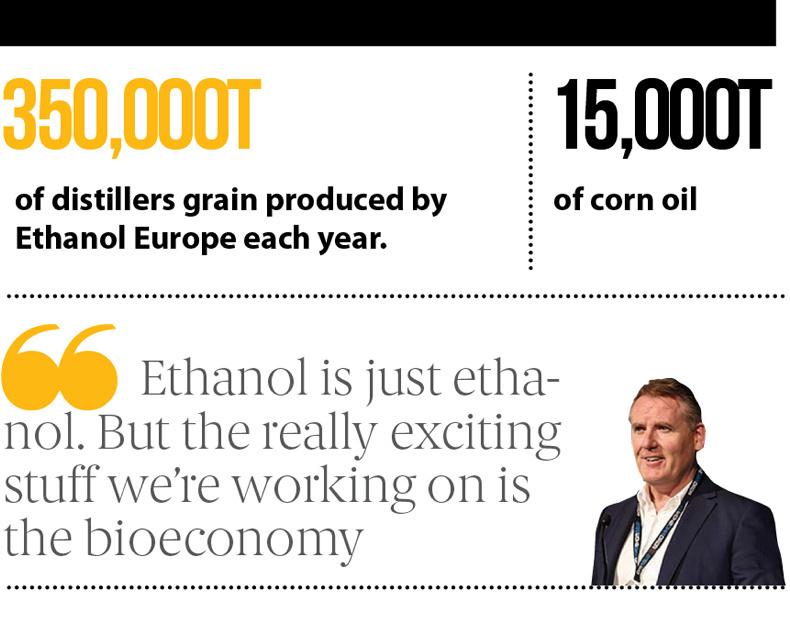

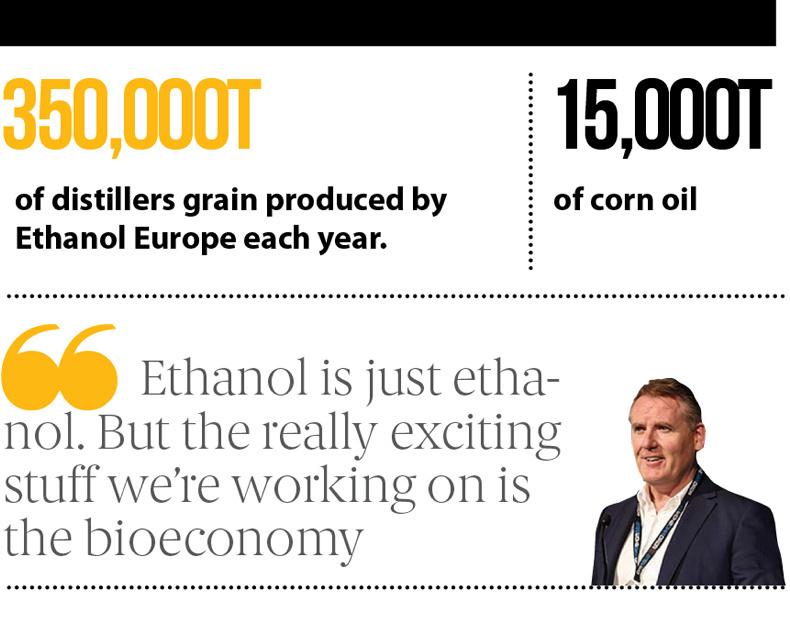

Ethanol Europe also produces 350,000t of dried distiller’s grain per year and 15,000t of corn oil, which are both byproducts of the ethanol distilling process. The distiller’s grain is sold for animal feed, typically at €150/t to €200/t, while the self-emulsifying corn oil can be used to feed heat-stressed animals through their water supply.

Ethanol Europe produces 350,000t of distiller’s grains.

For a man with no previous experience in the renewables sector, the scale of the business that Turley has built in Ethanol Europe over such a short space is impressive. However, he is not happy to stand still.

Over the next 12 months, Turley plans to transform his business from playing solely in the commodity ethanol sector and associated byproducts to a much more added-value and science-led business by focusing on what is known as the bioeconomy.

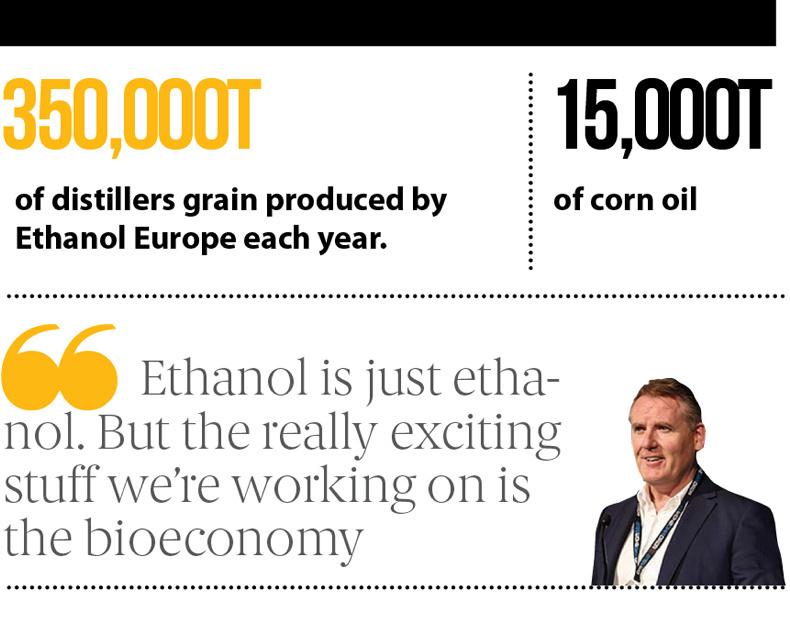

“Ethanol is just ethanol. But the really exciting stuff we’re working on is the bioeconomy,” says Turley. “Over the last three years we’ve spent €5m to €6m on novel bioeconomy projects. In 2018, we will spend €30m on new facilities at the ethanol plant in Hungary that will allow us to start extracting fibre from the maize corn.”

In the current process, what’s left from the ethanol process is used in animal feed. However, by extracting fibre from the maize corn, the company will have a new raw material that is extremely versatile in its applications.

Fibre can be used to make products such as cellulose and chitin. Cellulose is a natural polymer substance that can be used to make plastics and paper. Cellulose can also be used as a coating on paper cups or plates, which Turley believes will be in higher demand in the years ahead with countries in Europe like the UK and France moving to ban plastic straws and cups for environmental reasons.

Chitin is also a natural polymer and can be further processed into chitosan, which has a variety of uses, including in water treatment, biological plant protection, cosmetics or biomedical applications.

Because these products are found naturally in the environment they are biodegradable, unlike synthetic polymers.

Turley says his company aims to manufacture 3,000t of chitin by 2020. Another positive effect removing fibre from the maize corn is that it raises the percentage protein in the byproduct distiller’s grains.

In the normal process, the leftover distiller’s grains from making ethanol has a typical protein level of 30%. However, when the fibre is removed, the protein rate in the distiller’s grains will increase to over 40%, which Turley says could be a game-changer for Europe’s animal feed industry.

Soya replacer

“From next January, when we start taking the fibre out of the corn, our animal feed is going to go to over 40% protein. This immediately makes it a replacement protein source to the soya Europe is currently importing from the US and South America, which is genetically modified (GMO) and has antibiotics,” says Turley.

“I think this will be very interesting for the Irish dairy companies, particularly for making Kerrygold butter because GMO-free is becoming increasingly important for German consumers.”

However, the real point of differentiation for Turley’s company moving forward could be based much further up the value chain. The fibre extracted from the maize corn can be purified into a prebiotic, which are increasingly seen as good for maintaining gut and microbiome health.

“We have acquired the intellectual property rights (IP) for extracting a prebiotic from fibre from a Swedish company called Carbiotix,” says Turley. “We hope to supply Carbiotix with their fibre needs to make probiotics, which they sell to human consumers.”

Ethanol Europe.

Turley adds that the company plans to manufacture 5,000t of purified prebiotics from fibre in 2019 and has set up a company based in Dublin called PureFiber to commercialise prebiotic products made from fibre material for the animal feed, human health and nutraceutical sectors.

James Cogan is general manager with PureFiber and says the company is becoming more and more science-focused as it explores new applications for the fibre raw material.

“We’re heavily involved with University College Cork (UCC) at the moment. One of the world’s leading microbiome research facilities is in UCC and they are acting as scientific advisers for PureFiber,” says Cogan. “The research team in UCC will help carry out the clinical trials for the prebiotics we make for infants, elderly people and also animals.”

Cogan says the company will also benefit from the development of the national bioeconomy campus at Lisheen, Co Tipperary, on the site of the former Lisheen zinc mines.

The anchor project of this bioeconomy campus is the recently announced AgriChemWhey project, which will be led by Glanbia. The project was awarded €22m in EU funding and will take low-value dairy byproducts such as whey permeate and delactosed whey permeate and convert them into bio-based products such as biodegradable plastics and fertilisers.“We’re pushing the Government to bring the European bioeconomy summit to Ireland next year,” says Cogan. “We want to bring all the players in this sector together in one place.”

For Turley, the shift in focus towards the bioeconomy will become a greater part of the business in the coming years. Today, almost 80% of Ethanol Europe’s €24.1m in operating profits are generated from ethanol, with the remaining 20% derived from selling corn oil and distiller’s grains as animal feed. However, Turley believes the transitioning of the business towards the bioeconomy will transform his company and move it out of the commodity space. He forecasts that less than half of profits will come from ethanol by 2020 with new products such as prebiotics and chitin delivering new higher-margin profit streams for the business.

Read more

When is a meat company not a meat company?

How the kiwi fruit became New Zealand's main squeeze

In 2009, the EU adopted the Renewable Energy Directive (RED), which mandated for the first time that 10% of the transport fuel used by member states must come from biofuels by 2020. While oil companies were believed to be against it, the Renewable Energy Directive was just the opening Dublin businessman Mark Turley had been waiting for.

Mark Turley.

“I’d been looking at investing in renewables since 2007,” says Turley. “Most renewable energies need to be subsidised in order to make them work but ethanol was the exception.”

With the EU’s renewables directive in place, Turley and his team started a new business called Ethanol Europe and began construction in 2010 of a new biofuels plant. Located on the edge of the river Danube in Hungary, the plant required a capital investment of €150m, with construction completed in 2012, and had an initial capacity of 200m litres of ethanol per year.

Today, the plant in Hungary is pushing out 500m litres of ethanol a year, making Turley chief executive of Europe’s largest ethanol biorefinery with a 10% share of the 5bn litre market. Ethanol Europe takes in about 1.1m tonnes of maize corn every year, with about 60% sourced of this sourced directly from local farmers.

Abundant supplies

Turley says he chose Hungary as the location to build his ethanol plant because farmers grew abundant supplies of maize corn in the country but had little market for it. In the mid-2000s, Hungary accounted for 80% of all maize stocks offered into intervention at just €100/t.

Despite the electrical revolution taking hold in the car industry, Turley remains bullish on the long-term fundamentals of ethanol. Most large countries in Europe such as Germany and France already have 10% ethanol blended into their petrol fuels. However, Ireland and the UK still have just 5% ethanol in fuels.

By next year, both governments are expected to increase the ethanol mandate to 10% to meet targets under the EU’s renewables directive. Turley believes ethanol blends in Europe need to go as high as 25% to 30%, particularly as demand for liquid fuels in Europe is growing at 3% to 4% per annum.

Byproducts

Ethanol Europe also produces 350,000t of dried distiller’s grain per year and 15,000t of corn oil, which are both byproducts of the ethanol distilling process. The distiller’s grain is sold for animal feed, typically at €150/t to €200/t, while the self-emulsifying corn oil can be used to feed heat-stressed animals through their water supply.

Ethanol Europe produces 350,000t of distiller’s grains.

For a man with no previous experience in the renewables sector, the scale of the business that Turley has built in Ethanol Europe over such a short space is impressive. However, he is not happy to stand still.

Over the next 12 months, Turley plans to transform his business from playing solely in the commodity ethanol sector and associated byproducts to a much more added-value and science-led business by focusing on what is known as the bioeconomy.

“Ethanol is just ethanol. But the really exciting stuff we’re working on is the bioeconomy,” says Turley. “Over the last three years we’ve spent €5m to €6m on novel bioeconomy projects. In 2018, we will spend €30m on new facilities at the ethanol plant in Hungary that will allow us to start extracting fibre from the maize corn.”

In the current process, what’s left from the ethanol process is used in animal feed. However, by extracting fibre from the maize corn, the company will have a new raw material that is extremely versatile in its applications.

Fibre can be used to make products such as cellulose and chitin. Cellulose is a natural polymer substance that can be used to make plastics and paper. Cellulose can also be used as a coating on paper cups or plates, which Turley believes will be in higher demand in the years ahead with countries in Europe like the UK and France moving to ban plastic straws and cups for environmental reasons.

Chitin is also a natural polymer and can be further processed into chitosan, which has a variety of uses, including in water treatment, biological plant protection, cosmetics or biomedical applications.

Because these products are found naturally in the environment they are biodegradable, unlike synthetic polymers.

Turley says his company aims to manufacture 3,000t of chitin by 2020. Another positive effect removing fibre from the maize corn is that it raises the percentage protein in the byproduct distiller’s grains.

In the normal process, the leftover distiller’s grains from making ethanol has a typical protein level of 30%. However, when the fibre is removed, the protein rate in the distiller’s grains will increase to over 40%, which Turley says could be a game-changer for Europe’s animal feed industry.

Soya replacer

“From next January, when we start taking the fibre out of the corn, our animal feed is going to go to over 40% protein. This immediately makes it a replacement protein source to the soya Europe is currently importing from the US and South America, which is genetically modified (GMO) and has antibiotics,” says Turley.

“I think this will be very interesting for the Irish dairy companies, particularly for making Kerrygold butter because GMO-free is becoming increasingly important for German consumers.”

However, the real point of differentiation for Turley’s company moving forward could be based much further up the value chain. The fibre extracted from the maize corn can be purified into a prebiotic, which are increasingly seen as good for maintaining gut and microbiome health.

“We have acquired the intellectual property rights (IP) for extracting a prebiotic from fibre from a Swedish company called Carbiotix,” says Turley. “We hope to supply Carbiotix with their fibre needs to make probiotics, which they sell to human consumers.”

Ethanol Europe.

Turley adds that the company plans to manufacture 5,000t of purified prebiotics from fibre in 2019 and has set up a company based in Dublin called PureFiber to commercialise prebiotic products made from fibre material for the animal feed, human health and nutraceutical sectors.

James Cogan is general manager with PureFiber and says the company is becoming more and more science-focused as it explores new applications for the fibre raw material.

“We’re heavily involved with University College Cork (UCC) at the moment. One of the world’s leading microbiome research facilities is in UCC and they are acting as scientific advisers for PureFiber,” says Cogan. “The research team in UCC will help carry out the clinical trials for the prebiotics we make for infants, elderly people and also animals.”

Cogan says the company will also benefit from the development of the national bioeconomy campus at Lisheen, Co Tipperary, on the site of the former Lisheen zinc mines.

The anchor project of this bioeconomy campus is the recently announced AgriChemWhey project, which will be led by Glanbia. The project was awarded €22m in EU funding and will take low-value dairy byproducts such as whey permeate and delactosed whey permeate and convert them into bio-based products such as biodegradable plastics and fertilisers.“We’re pushing the Government to bring the European bioeconomy summit to Ireland next year,” says Cogan. “We want to bring all the players in this sector together in one place.”

For Turley, the shift in focus towards the bioeconomy will become a greater part of the business in the coming years. Today, almost 80% of Ethanol Europe’s €24.1m in operating profits are generated from ethanol, with the remaining 20% derived from selling corn oil and distiller’s grains as animal feed. However, Turley believes the transitioning of the business towards the bioeconomy will transform his company and move it out of the commodity space. He forecasts that less than half of profits will come from ethanol by 2020 with new products such as prebiotics and chitin delivering new higher-margin profit streams for the business.

Read more

When is a meat company not a meat company?

How the kiwi fruit became New Zealand's main squeeze

SHARING OPTIONS