Benchmarks, crowsfeet, sappers’ marks, trigmark, the devil’s mark, three-legged stool – these are the names commonly given to the mark the surveyors of Ordnance Survey Ireland chiselled into stones all over Ireland in the 19th and early 20th century.

What do they look like?

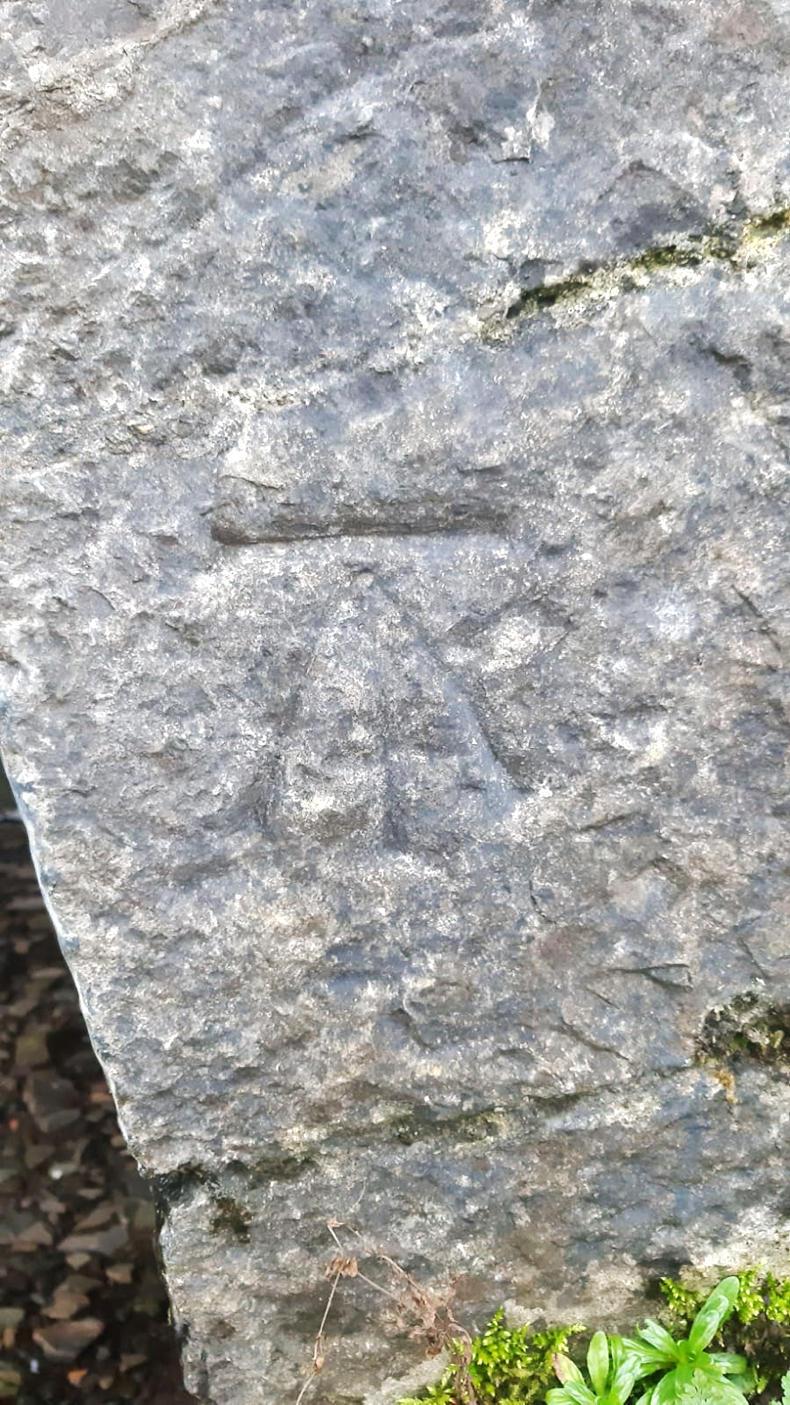

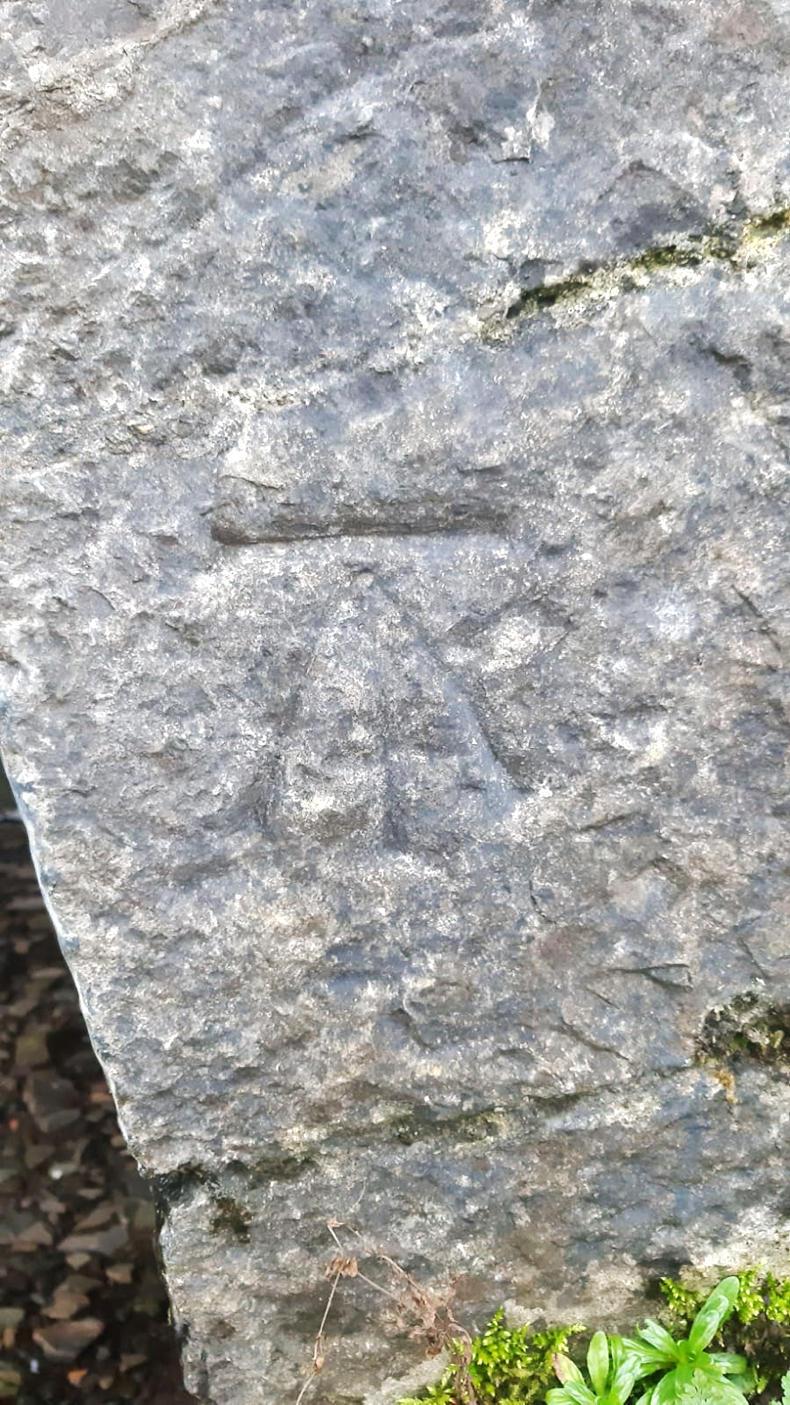

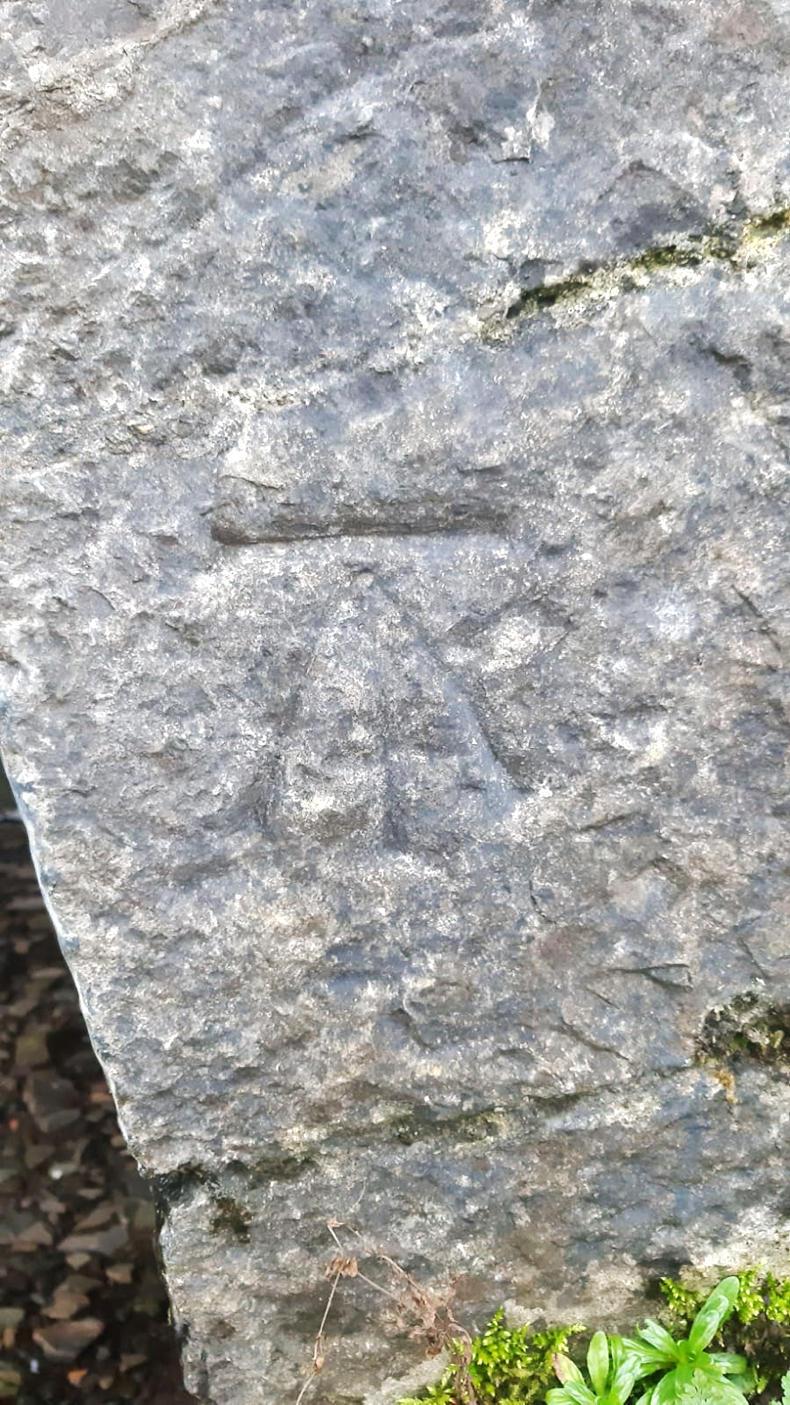

An arrow pointing at a horizontal line (Fig 1 and 2) or a dot above (Fig 3).

Figure 2: Inistiogue, opposite well.

The dot version is used on horizontal surfaces like railings of bridges or flat lying stones. When the stone has been moved during a relining of a wall, it can appear upside down (Fig 2).

Figure 3: Bishopslough.

What do they mean?

The surveyors mapping Ireland in the 19th century used benchmarks as points for measuring the height above sea level. The fundamental reference points were the low water of spring tides in Dublin Bay and the Poolbeg Lighthouse. Surveyors placed their measuring rod either in the horizontal line or the dot, took their measurements and used triangulation to determine the height of this particular point above sea level. In theory, one should be able to see two other triangulation points standing at the location of the benchmark.

The locations of the benchmark were then added to the Ordnance Survey maps using the same symbol. Before the time of GPS, this was a good way to provide the location to the next generation of surveyors to retake measurements. Oftentimes, the height above sea level differs between the several OS maps, one must presume due to mathematical and measurement errors that of course continue on in a triangulation system.

Where were the benchmarks used?

In towns, benchmarks were carved into buildings then thought to be permanent structures such as public buildings: church entrances, church gateposts, courthouses (Kilkenny, Athy, Gowran, Kilmainham), town halls (Kilkenny) and other historical buildings (Rothe House in Kilkenny, Reginald’s Tower in Waterford). They were also found on jostle stones at the entrance to laneways (Chapel Lane, Kilkenny) or house entrances. Jostle stones were used to keep the wagon wheels from scratching the walls. Sometimes, benchmarks were found on railway bridges, both at street level, but also sometimes at track level.

Figure 4: Coolbricken bridge painted.

In rural areas, benchmarks were very often carved into bridges, because it was very easy to find a bridge when the next generation surveyor came along.

Figure 5: Bennetsbridge.

There were three places to carve a benchmark into a bridge: roughly in the middle of the bridge facing the road (Fig 4), on top of the bridge (Fig 5) or – very awkward when looking for them now - facing the water (Fig 6).

Other rural spots were gateposts, especially at field entrances. Of course, church walls were also used in rural areas.

Figure 6: Castlewarren Bridge.

Some benchmarks can be found on farm buildings, but this is not very common as far as the author has ascertained. Might the reason be that farmers were not very welcoming towards British sappers?

When the terrain required it, benchmarks seem to have been left along field borders as well. Very few of these survive, so it is difficult to say now what material was used to chisel the marks into.

Where are they now?

Nowadays, surveyors can use GPS, so the benchmarks have become redundant. However, they are a part of Irish heritage and in some places folklore. They belong to whoever owns the stone structure they are on.

In urban areas, benchmarks survive, if the building has survived. Churches, court houses etc are still displaying them to this day. On private houses, they are often rendered over. However, in rare cases the plasterer left the benchmark exposed (Fig 7 and 8). Jostle stones have also fallen out of use, so many of those benchmarks are lost as well.

Figure 7: Old Sion Road.

Many of the benchmarks were lost when entrances into fields were widened to make room for bigger machinery. Nobody could foresee the size of modern combine harvesters in the 1840s. They were probably carved into the old round gateposts. Walls were often relined and the stone bearing the benchmark was either lost or re-used and is now not in the original location. Rural bridges (and remaining gateposts) are often overgrown and make it challenging to find benchmarks.

Figure 8: Cramersgrove.

There are a few people in Ireland who have made discovering benchmarks a pastime or a research topic. They can be spotted by intensely staring at old walls or trying to clear overgrown walls. The author is trying to add as many as possible to OpenStreetMap.org, the Wikipedia for mapping. A map of confirmed locations can be found at http://u.osmfr.org/m/402828/.

The farmer from whom Anne-Karoline is renting also had an interest in benchmarks, because he has one on one of his buildings. He was very interested indeed to learn that there should be two more on his property. Have you any on your farm?

If you are interested in adding benchmarks you know about, Anna-Karoline has made a YouTube tutorial to help with that, search for.

Read more

‘My cow has angle berries on her dug’ – local names for everyday issues

Reader writes: the Abbey at Holy Cross

Benchmarks, crowsfeet, sappers’ marks, trigmark, the devil’s mark, three-legged stool – these are the names commonly given to the mark the surveyors of Ordnance Survey Ireland chiselled into stones all over Ireland in the 19th and early 20th century.

What do they look like?

An arrow pointing at a horizontal line (Fig 1 and 2) or a dot above (Fig 3).

Figure 2: Inistiogue, opposite well.

The dot version is used on horizontal surfaces like railings of bridges or flat lying stones. When the stone has been moved during a relining of a wall, it can appear upside down (Fig 2).

Figure 3: Bishopslough.

What do they mean?

The surveyors mapping Ireland in the 19th century used benchmarks as points for measuring the height above sea level. The fundamental reference points were the low water of spring tides in Dublin Bay and the Poolbeg Lighthouse. Surveyors placed their measuring rod either in the horizontal line or the dot, took their measurements and used triangulation to determine the height of this particular point above sea level. In theory, one should be able to see two other triangulation points standing at the location of the benchmark.

The locations of the benchmark were then added to the Ordnance Survey maps using the same symbol. Before the time of GPS, this was a good way to provide the location to the next generation of surveyors to retake measurements. Oftentimes, the height above sea level differs between the several OS maps, one must presume due to mathematical and measurement errors that of course continue on in a triangulation system.

Where were the benchmarks used?

In towns, benchmarks were carved into buildings then thought to be permanent structures such as public buildings: church entrances, church gateposts, courthouses (Kilkenny, Athy, Gowran, Kilmainham), town halls (Kilkenny) and other historical buildings (Rothe House in Kilkenny, Reginald’s Tower in Waterford). They were also found on jostle stones at the entrance to laneways (Chapel Lane, Kilkenny) or house entrances. Jostle stones were used to keep the wagon wheels from scratching the walls. Sometimes, benchmarks were found on railway bridges, both at street level, but also sometimes at track level.

Figure 4: Coolbricken bridge painted.

In rural areas, benchmarks were very often carved into bridges, because it was very easy to find a bridge when the next generation surveyor came along.

Figure 5: Bennetsbridge.

There were three places to carve a benchmark into a bridge: roughly in the middle of the bridge facing the road (Fig 4), on top of the bridge (Fig 5) or – very awkward when looking for them now - facing the water (Fig 6).

Other rural spots were gateposts, especially at field entrances. Of course, church walls were also used in rural areas.

Figure 6: Castlewarren Bridge.

Some benchmarks can be found on farm buildings, but this is not very common as far as the author has ascertained. Might the reason be that farmers were not very welcoming towards British sappers?

When the terrain required it, benchmarks seem to have been left along field borders as well. Very few of these survive, so it is difficult to say now what material was used to chisel the marks into.

Where are they now?

Nowadays, surveyors can use GPS, so the benchmarks have become redundant. However, they are a part of Irish heritage and in some places folklore. They belong to whoever owns the stone structure they are on.

In urban areas, benchmarks survive, if the building has survived. Churches, court houses etc are still displaying them to this day. On private houses, they are often rendered over. However, in rare cases the plasterer left the benchmark exposed (Fig 7 and 8). Jostle stones have also fallen out of use, so many of those benchmarks are lost as well.

Figure 7: Old Sion Road.

Many of the benchmarks were lost when entrances into fields were widened to make room for bigger machinery. Nobody could foresee the size of modern combine harvesters in the 1840s. They were probably carved into the old round gateposts. Walls were often relined and the stone bearing the benchmark was either lost or re-used and is now not in the original location. Rural bridges (and remaining gateposts) are often overgrown and make it challenging to find benchmarks.

Figure 8: Cramersgrove.

There are a few people in Ireland who have made discovering benchmarks a pastime or a research topic. They can be spotted by intensely staring at old walls or trying to clear overgrown walls. The author is trying to add as many as possible to OpenStreetMap.org, the Wikipedia for mapping. A map of confirmed locations can be found at http://u.osmfr.org/m/402828/.

The farmer from whom Anne-Karoline is renting also had an interest in benchmarks, because he has one on one of his buildings. He was very interested indeed to learn that there should be two more on his property. Have you any on your farm?

If you are interested in adding benchmarks you know about, Anna-Karoline has made a YouTube tutorial to help with that, search for.

Read more

‘My cow has angle berries on her dug’ – local names for everyday issues

Reader writes: the Abbey at Holy Cross

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: