At the time of the Great Famine in the mid-1800s, Irish people were very dependent on potatoes as their staple diet. However, by 1916 the number of acres of the crop had almost halved. There was a significant move from crop growing to animal farming. Ploughed land decreased from 4.4m acres in 1849 to 2.4m in 1916. At the same time, land in pasture doubled. This increase in pasture was linked to an increase in livestock numbers, especially grazing animals.

Livestock farming

From 1848 to 1916 livestock numbers rose dramatically. Due to their importance from a labour and status point of view, there was a significant increase in the number of horses, mules and asses. However, the main increase came in the numbers of cattle and sheep.

Cattle

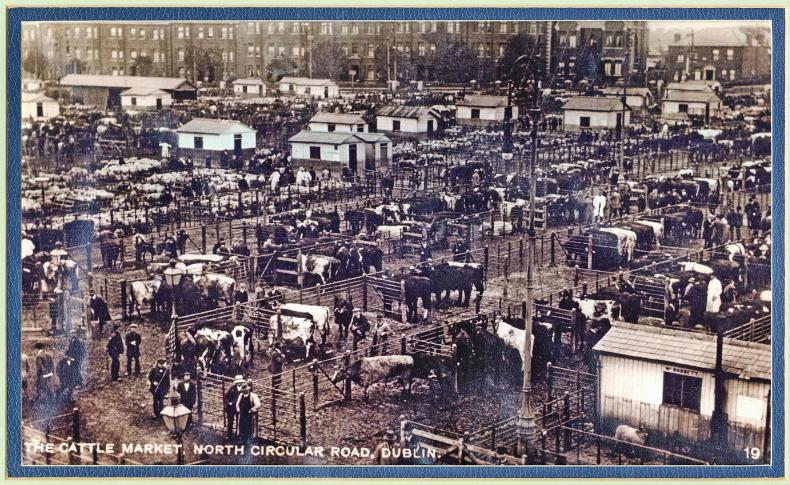

Cattle numbers rose from 2.7m in 1848 to 5m in 1914 throughout the island. In the period from 1910 and 1914, cattle numbers rose by 20%. With an emphasis on dairy, this led to the growth of creameries to over 1,000 throughout Ireland.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Shorthorn was the dominant breed of cattle. While this was predominantly a beef breed, efforts were being made to select Shorthorns for their milking ability, thus giving them a dual purpose role.

In 1900, the Department of Agriculture began registering pure-bred bulls, with Shorthorns accounting for 65% of the total.

The next largest group was the Aberdeen Angus with 6%, followed by the Hereford with 2.5%. The Galloway also featured at that time.

Over a quarter of the bulls registered were described as crossbred. Only two native Irish breeds survived: the Kerry and the Dexter. The Kerry was prominently used for milk and the Dexter for beef. Together they accounted for 2.5% of the Department of Agriculture’s approved bulls in 1900.

Sheep

Sheep numbers also grew significantly from 2m in 1848 to 3.6m in 1914. Interestingly, this is a very similar number as at the end of 2014, a century later.

One major advantage of sheep was that they could be kept on poor-quality pasture at very little cost. They were kept for two products: mutton (sheep meat) and wool. Both were exported to Britain as well as large numbers of live sheep. However, large volumes of wool were being imported from the Southern Hemisphere, reducing the value of wool at home.

Furthermore, in the late 19th and early 20th century, frozen mutton was also being imported from the Southern Hemisphere. These issues forced farmers to place a greater emphasis on the value of producing fat lambs efficiently.

The main sheep breeds included the Roscommon, a long-wool breed. This was a large, white-faced sheep, somewhat similar to the Galway breed but larger.

While the Galway breed was prominent in the early 20th century, the breed association was not established until 1923.

Today, nearly 100 years later, it is reportedly Ireland’s only native sheep breed. Other prominent breeds included the Border Leicester, the Wicklow sheep and the Down breeds (most likely the Oxford Down), which were commonly crossed with other breeds to produce fast-growing lambs with good meat quality.

On the hills, the Blackface Mountain and Cheviot were prominent, being hardy and able to withstand difficult conditions. The Kerry Hill also featured, which originated in Kerry, Wales rather than in Co Kerry, Ireland.

Pigs

Pigs were very popular on most farms during this time, as they could be fed cheaply on foods like potatoes, fodder crops and left-overs from cooking. The main breeds included Large White Yorkshire and Large White Ulster.

While pigs were commonly grazed on grassland, skim milk and buttermilk with barley, and potatoes were commonly used to fatten them.

Therefore, finishing pigs for slaughter was popular in strong dairy areas, such as Munster and in the East of the country. This resulted in many pig factories being set up, with 19 bacon factories throughout the country in 1900.

Pigs were part of an important daily diet throughout Ireland and were regularly slaughtered on the farm for home consumption. The lard from pigs was used for cooking cabbage, with bacon and potatoes, a very popular dinner in most households – as it remains today.

Pigs were also reared for sale and most farms tried to rear some pigs for the market each year. This provided additional income, which was particularly important, with the income from pigs on many small farms being almost as great as that from cattle.

Poultry

There was significant growth in the export of eggs and poultry products in the 20th century. Eggs were commonly sold in markets, being brought there by the woman of the house and sold by the dozen or score.

Traders known as “higlers” also bought eggs from farms and sold them on, usually for export.

While overall poultry numbers and value increased, the industry remained small-scale, largely operated by the women on the farm.

While turkeys, ducks and geese were significant, hens were the dominant bird, with nearly 19m hens throughout the island of Ireland in 1902.

In 1909 the dominant breeds of hens were White Leghorn, Brown Leghorn, Buff Orpington and White Wyandotte. By 1915 additional breeds included Black Orpington, Blue Orpington, Ancona and Andalusian.

Generally, hens roamed throughout the yard but by 1919, people realised that if they were confined to smaller yards they would lay more eggs and fatten quicker than if roaming over a larger area. By confining them to the smaller areas, they could lay up to 200 eggs in a year, as opposed to the average of 100.

Furthermore, hens were regularly kept in the dwelling house for heat, encouraging them to lay eggs throughout the winter when otherwise they might not.

In 1913 the value of eggs exported was £3m, but this rose sharply to £15m by 1919, with a further £3 million in exports of poultry meat and feathers, bringing the total value of the poultry industry to £18m, which was almost equal to the value of exports of cattle.

Agriculture: a thriving industry

While many believe that Irish agriculture was going through difficult times in 1916, it actually experienced a boom 100 years ago.

The period 1914 to 1918 saw incomes rise in absolute terms, due to increases in commodity prices. There was very strong demand for food from Britain.

Prices rose sharply from 1914, with cattle and butter up 50% and the doubling of barley prices. By 1916, nearly 80% of the average farmer’s income came directly from livestock, with only 20% from crops. CL

SHARING OPTIONS