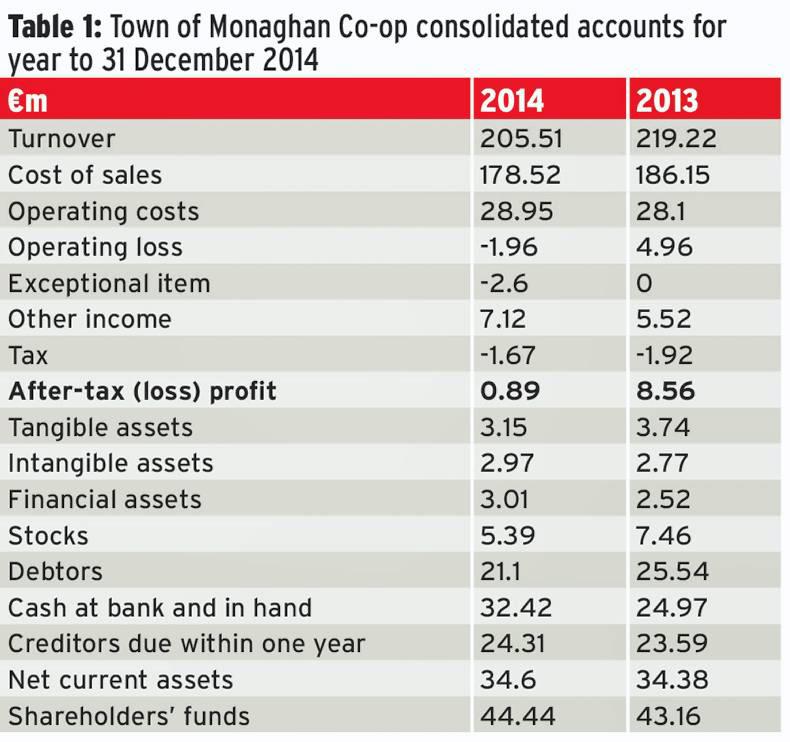

An operating loss of €1.96m on turnover of €205.5m in the year to 31 December 2014 did little to dent the balance sheet at Town of Monaghan Co-op, where the previous year saw operating profit of €4.96m on turnover of €219.2m. Gross profit at €27m was down by over 18%. The reduced margin and the operating loss indicates that the Monaghan co-op passed a bigger portion of its 2014 revenue on in milk prices paid to producers.

Sale of shares meant that the group declared a profit of €0.89m after tax of €1.67m. That was after provision for an exceptional additional cost of €2.6m.

According to chief executive Gabriel D’Arcy, the exceptional item includes ‘‘significant provisions’’ associated with business restructuring and milk pricing.

The €7m gain from the sale of shares in Aryzta plc follows the sale of around €5m worth of Aryzta shares in 2013, when the Monaghan operating profit was a record €4.96m and after-tax profit reached almost €9m.

The quoted value of shares held at the end of 2013 was €26.3m, and these were in the balance sheet at a cost of €0.49m. There is potentially a lot more cash gain available from that source.

The group balance sheet indicates €32.4m cash in the bank at the end of 2014, with positive cashflow of over €7m in 2014 added on top of €16.8m in 2013.

This could go a large part of the way to fund investment in the proposed state-of-the-art drying plant at the Artigarvan factory of the newly born LacPatrick Co-op, formed from the recent merger of Monaghan and Ballyrashane co-ops.

Decisions

Going ahead with that investment will be one of the first big decisions for the board of LacPatrick.

According to D’Arcy, there is a need for additional capacity. The co-op had to sacrifice some milk in 2014 and was processing sub-optimally (producing butter and skim powder instead of branded whole milk powder) during the peak supply period in 2015 just to deal with the high volumes of milk.

Investment by Ornua (formerly the Irish Dairy Board) in butter manufacturing is a threat, given that approximately 40% of Town of Monaghan’s packet butter business was for the Kerrygold brand. D’Arcy sees this as ‘‘a challenge and an opportunity’’.

Milk supply stabilised

In his report to the AGM last week, Town of Monaghan chair Hugo Maguire said that the co-op’s milk supply had stabilised and was “beginning to grow strongly again following a difficult few years of predatory actions by other processors”.

This is a reference to the open competition that came into the market when Fane Valley Co-op started to purchase milk directly from farms in April 2012, instead of buying milk through United Dairy Farmers.

D’Arcy paid tribute to former chief executive, Vincent Gilhawley, who served for 27 years “during which the co-operative had doubled in size and generated as strong a balance sheet as exists in the Irish dairy sector”.

Gilhawley has taken on the role of company secretary with the group.

Apart from its cash pile, tangible fixed assets within the Monaghan group at December 2014 were considerably depreciated at just over €3m, with a further €2.97m of intangible assets and just over €3m listed as financial assets.

Lobbying continues over milk prices

The lobbying effort designed to get the European Commission to step in and increase the intervention safety net on milk prices continued on Tuesday of this week, with Agriculture Minister Michelle O’Neill leading a delegation to meet DEFRA secretary Liz Truss.

A separate NI delegation involving local farmers and processors and led by Upper Bann MP David Simpson also lobbied Secretary Truss on Wednesday.

At the meeting involving Minister O’Neill, she was joined by Ulster Farmers’ Union (UFU) president Ian Marshall and Dr Mike Johnston from Dairy UK.

Speaking after the meeting, the minister said that there had been a “frank and constructive discussion” with Secretary Truss.

“Liz Truss acknowledged that we have a unique and extreme set of circumstances facing dairy farmers in the North. She said that she was committed to taking action and I will meet her again next week, along with Scottish and Welsh ministers, to continue to press her to take that action,” said Minister O’Neill.

With the British government keen to cut European spending and supporters of the free market, it is a problem for the local industry when they lobby in Europe for increased safety net prices, only to find that their own government is against the idea.

Despite the political efforts to solve the crisis in the dairy industry, and the call from the UFU for local protests to end, a group of around 60 farmers blocked heavy goods vehicles entering or leaving the Lidl distribution centre at Nutt’s Corner in Antrim on Tuesday night.

They were joined by Farmers For Action (FFA) UK Northern Ireland co-ordinator William Taylor. He said: “With everything that is going on in farming, Farmers For Action across the UK wants to let everyone know how bad things are, not just for milk producers but across the board in all sectors.”

Targeting the protests

Media coverage of ongoing protests about milk prices has made the non-farming public aware of the current plight of dairy farmers. Many of the protesters are committed young dairy farmers and they’ve been joined by others who aren’t in dairying but are suffering just the same.

Where will it lead? It’s more than ironic when the protests are occurring at the premises of the retailers who are paying the best prices available for processed milk in NI. How will they react?

Morrisons, which has no stores in NI, has been under attack as the only large multiple retailer in the UK that doesn’t have a special pricing arrangement for farmers supplying milk for sale on its shelves.

Morrisons has now come up with a proposal to sell a premium-priced milk and pass back extra payment to the suppliers of that milk.

The other large retailers have been trying to point out that they operate various special pricing schemes for their milk, linked to specific suppliers. Some of these payment schemes are linked to cost of production, which is assessed by independent consultants every six months or more often, with the price adjusted in line with costs.

Tesco operates such a scheme, but announced recently that it is going to be reviewed.

Division

Supermarkets selling liquid milk in NI account for less than 5% of the milk output from local farms and they pay a premium for it. If that premium is directed only to the small number of farmers who supply that milk in NI – as occurs in England – it threatens to create a great division among producers here and it will undermine the co-operative principle, whereby all members of the co-op have a share of the premium that is paid on liquid milk. In England, this has certainly given some farmers a much better milk price than others.

Such an outcome here is not going to solve the pricing problem for the majority. The pressure needs to be targeted at our political masters and the European Commission in Brussels, who are the only ones with power to do something to put a realistic floor in the market.

The farming unions of EU member states are staging a protest demonstration in Brussels on 7 September to coincide with a special meeting of the EU Council of Ministers of Agriculture. That’s where farmers from Northern Ireland can join others from all over the EU to press the political buttons.

Intervention base prices

On inquiry, a spokesperson for EU Commissioner for Agriculture Phil Hogan has confirmed to the Irish Farmers Journal that it would take up to 18 months to get a change in intervention base prices.

According to the spokesperson, full co-decision is required with the European Parliament.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: