One of the largest agricultural conferences in the world took place in Brussels last Tuesday, the brainchild of former European Agriculture Commissioner Franz Fischler.

With 1,500 delegates and 25 speakers and panellists, the topics covered everything from climate change to food security, with many of the world’s and Europe’s key players participating.

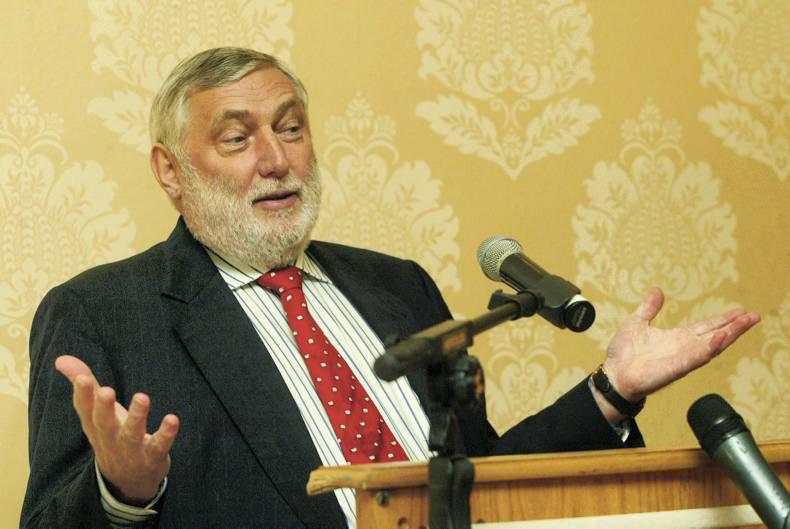

The first main speaker was the still new Commissioner for Agriculture and Rural Development Phil Hogan. He gave an assured performance, especially when compared with his predecessor Dacian Ciolos.

While noting with approval that he was speaking on the last day of the milk quotas, he was unapologetic in saying that the primary aim of the CAP was food production or, as he put it, the obligation to end food insecurity. He wants the policy to enhance overall competitiveness, to encourage innovation, to be non-trade distorting – while farmers, he said, were entitled to policy consistency from Europe.

He noted that export refunds were no longer part of normal EU policy. The EU is now both the biggest importer of agricultural products in the world and the biggest exporter – mainly of high-value-added food and drink products.

Nine billion people by 2050

Speaker after speaker referred to the nine billion people we can expect to see in the world by 2050, which they all agreed was going to need an increase in raw food production by 60% to 70% because of the move by the increasingly well-off consumers to more meat and dairy products.

The deputy head of the United Nations’ Food and Agricultural organisation (FAO) developed this theme by saying that the increased output needed was going to have to come mainly from increased yields on the existing land base. However, several drew attention to plateauing yields observed especially in Europe at the same time as extra volatility and a rundown of public stocks.

Meanwhile, the proliferation of production standards set by the processing and retailing industries is leading to unnecessary large-scale food waste.

Irish farmers’ problems are shared elsewhere with repeated calls for a fairer allocation of the money spent on food and a proper code – with teeth – to govern the relationship between farmer, processor and retailer.

The Commission was also criticised for its slowness to authorise new technologies and its readiness to reduce the availability of effective active ingredients.

Special trade session

The EU and US agricultural policies are moving in different directions and the likelihood of a trade deal has diminished. The two US speakers, former IMF deputy managing director Anne Krueger and professor Bob Young of the Farm Bureau, both agreed that agriculture would have to be an integral part of any EU-US trade deal, yet it did not look as if President Obama would be given the authority to negotiate a deal at this stage.

In effect, no progress has been made and the US has moved to a more coupled price support system under the new Farm Bill, while the EU has successfully decoupled payments from products as it moves to a farm income-based policy.

There is also a quality stalemate with full assurances from the principal European agricultural negotiator that the EU was not going to sacrifice its standards. John Clarke said hormone-treated beef was simply not going to be let into Europe in any final deal, but he could foresee guaranteed non-hormone-treated, grain-fed US beef having a valid place in a high-quality European market. Broadly, he saw beef, poultry and rice as sensitive products for Europe because of the higher quality and higher costs of European production.

European Parliament vice president Mairead McGuinness, just back from Washington, agreed with the assessment that a US-EU deal was not on the cards at this stage. Yet, she added that now was the time to build in safeguards in areas such as dispute resolution and the protection of Europe’s quality standards.

Surprises

There was widespread acceptance that incentives to reduce fossil fuel and produce renewable energy (through price increases) should help farms become carbon neutral, including from US-based Jeremy Rifkin of the Foundation on Economic Trends who probably gave the most provocative speech of the conference.

He held the audience spellbound with a mixture of unconventional viewpoints and appeals to common sense. He also drew attention to the huge potential of sensors for gathering data, for example, to tailor inputs in farming.

But Rifkin is deeply sceptical of the trend towards increasing consumption of meat and dairy products – he wants to see and recommends more grain for food, not for animal feed, and a reduction in the number of ruminant livestock because of their greenhouse gas emissions. Some of his views might not appeal to farmers, but there is little doubt that his original thoughts and recommendations should be carefully analysed before being discarded.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: