Last week’s arable conference in Greenmount expounded the theme ‘max yield from the field’. It focused on matters pertaining to yield, its generation and its maximisation at field level. The conference was organised jointly by CAFRE, the Ulster Arable Society and the Ulster Farmers Union. While many different topics were addressed, soil health and quality was a common thread in the presentations.

Yield is the driver of profit

The challenge in tillage is to be at the right end of the ranges of cost, yield and price. Robin Bolton of CAFRE outlined the results of the 2014 benchmarking survey, which included 55 farms with 5,582 acres of combinable crops. Farm size ranged from 30 to 700 acres, with an average of 96 acres.

The average crop yield was 2.5t/ac, which is a mix of all crops including oilseed rape. The average price achieved was £123/t (from £100/t to £139/t) and oilseed rape was present in the prices at the higher end of this range.

The average production cost per tonne was £141 and this ranged from £56 to £224/t. Production cost included hired labour, but not family or own labour.

The individual combinations of yield, cost and price then left an average profit level of -£18/t before support payments. Profit per tonne ranged from -£138/t to £72/t, depending on the farm.

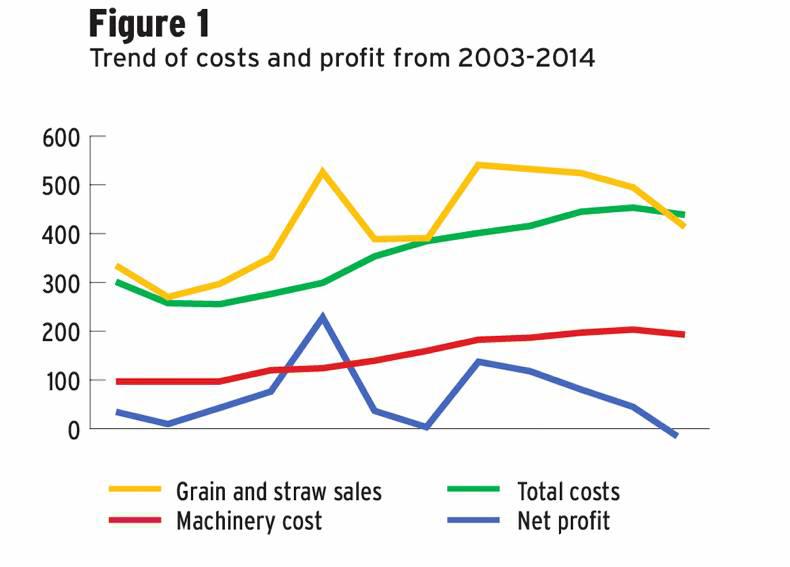

In Figure 1 above, Robin showed that machinery costs have doubled on farms since 2003, from £100 to £200/ac, and there has also been an increase in other costs during this same period. When the trend in profit was graphed, it was obvious that it followed the exact same shape as the value of total crop sales – grain plus straw.

Of the three components of profit – price, costs and yield – growers must challenge each one all the time, but there is a limit as to what one can do. Expressed on a per-acre basis, Robin showed that the top 25% of growers tended to have slightly lower expenditure on seed and fertiliser, but they were similar on most other costs.

However, when costs were expressed on a per-tonne basis, differences became more obvious, because the better performers had higher yields. Now the top 25% had spent about £8/t less on seed and fertiliser than the bottom 25% and they were also lower on every other cost category. The average total production cost per acre was £440 and this was categorised as one-third variable and two-thirds fixed costs.

Yield remains a very important factor in terms of retained margin. Based on the findings of the study, a yield increase of 0.1t/ac decreased the cost by £5/t. So a grower who could achieve a yield level of 0.25t/ac above the average would decrease production cost by £12.50/t.

Robin emphasised the need for growers to get better before they get bigger, as yield remains the main driver of profitability. That said, cost level and selling price are also important.

Drive biomass and tillers

Spring barley remains the main crop on the island and also in Northern Ireland.

John Spink of Teagasc spoke about the pathway to maximising yield potential in spring barley and stated that grains per unit area drives yield potential.

And these research findings, which provided the background information for the Teagasc Spring Barley Growth Guide, were confirmed by AFBI research in 2013 and 2015.

John said that barley is different to wheat in this regard, in that wheat yield is more impacted by grain fill and, because of this, prolonged grain fill is more important in this crop.

Temperature drives crop development (the transition from stage to stage), but solar radiation or heat drives crop growth.

These two then interact to impact on crop performance each season.

John showed how cooler weather in Carlow in 2011 had prolonged the growing season and how longer grain fill resulted in better fill and quality.

Large biomass

In barley, the generation of large biomass (bulk of growth) early in the season will generally carry through to high yield potential.

However, crops can recover from a slower start, but the extent of any recovery depends much more on a favourable period for grain fill.

Big early season biomass production in barley produces reserves which are stored in the canopy in leaves and stems.

These reserves can be used to support grain fill later in the season if growth is limited by either poor radiation or foliar disease.

For this reason, early disease control is very important to enable maximum biomass production and to prevent the loss of leaves and stems which are used to store these reserves.

Early season crop development is crucial to generate the optimum final ear number of around 1,000 ears per square metre.

John said that high-yield spring barley crops must start with an adequate plant stand.

He advised growers to plant around 350 seeds/m2, prevent early nutrient stress, keep crops free of disease early on and to control weeds early to avoid competition for nutrients and light.

Prolonging the grain filling periods is generally unlikely to result in yield increase in spring barley, he concluded.

Attention to detail essential for yield

Colin McGregor runs a core family farm business on 304ha in Coldstream Mains on the Scottish-English border. He also contract farms a further 3,169ha in 14 separate business transactions. These are all within 17 miles of the home base and farmed on the basis of winter cropping plus spring break crops. “This is not about ranching,” Colin insisted, “it’s about yield and making economies of scale work.

“When we first entered contract farming, such arrangements were scorned upon. Now it has become socially acceptable to have someone else farm your land and such arrangements are seen as sensible, even clever,” Colin stated.

He said that these are all real arrangements where risk is taken on by both parties and are all quite individual to suit the needs of both parties.

With yield at the core of the success of these operations, rotation is key to delivering success, Colin stated. Depending on the land, he operates either a six- or an eight-year rotation. The crops include winter wheat, winter barley, oilseed rape, vining peas, spring beans, and potatoes.

He said that his bean area is decreasing and that winter barley yields have improved in recent years. But winter wheat is his main crop with almost 1,600ha, followed by oilseed rape (553ha) and winter barley (330ha).

Precision farming

He has invested heavily in recent years and this has facilitated the growth in his business. He now has 8,500t of storage capacity on the home farm, plus access to an additional 25,000t on the other farms. Colin has also invested heavily in technology to make the whole system work better. This includes many precision farming technologies based on RTK precision.

He uses conductivity-based soil testing and variable rate fertiliser application. He also uses variable rate seed drilling. He estimates that these technologies are worth £27/ha to his business. He also uses yield mapping and machine telematics.

“Big acres mean big kit and big cost,” he commented. Colin tries to balance age with acres in terms of machinery investment. In 2009, he had three tracked combines, with a combined header width of 27m (90 feet). In 2014, he still had three combines, but the combined header width was increased to 36m (120 feet).

Colin stated that 2015 was his best ever yield year. Yields of all crops have been increasing over time, but there have been occasional dips due to poor years.

Average farm wheat yield in 2015 was 11.8 t/ha, with winter barley at 10.44t/ha. And his average yield of spring beans was 8.27t/ha.

Converting solar radiation into yield

The Yield Enhancement Network (YEN for short) sets about trying to quantify both the capability of yield level and the efficiency with which it is delivered.

The network is headed up by Roger Sylvester-Bradley from ADAS and it attempts to gather information about the factors that affect yield in the fields.

Yield potential may be set to some degree by weather, but we must be able to manage our crops within the weather we get, Roger stated.

Photosynthesis is critical for food production as it is the mechanism by which solar radiation energy is converted to food energy.

And yet, despite its importance, we do not measure solar energy in our everyday lives. Basically, light makes sugars from carbon dioxide and water. Put simply, solar energy capture equates to crop growth potential.

Roger suggested that the majority of southern Ireland receives an average of 40TJ (terrajoules) of solar energy per hectare per annum.

This figure is put at 36TJ across northern and western Ireland. And we can produce 1t of biomass per hectare for every 1.4TJ of solar energy.

Put in context, Roger said that on a bright summer’s day, one square metre of wheat crop produces one slice of bread, but that this falls to one-third on a dull summer’s day.

The YEN process is attempting to produce a new dashboard to measure and monitor growth in wheat. It is working to understand the variables encountered in normal crop life. This requires a big number of samples to measure the structure of each specific crop.

There is some work involved in being a YEN participant, but it is not that big relative to the benefits that can be achieved.

Participation requires the assembly of background information to support the research. Growth is about the capture of water and light and management requires that we structure a wheat crop to intercept light efficiently and keep it alive for as long as possible for grain fill. YEN is not about maximum yield – it is about the efficient delivery of yield potential from any site.

Research to date from 2013, 2014 and 2015 crops has shown that total biomass production is the most important factor identified as associated with high yield delivery.

Nutrition involves 13 nutrients

Crop nutrition is critical for the generation of maximum yield, but legislative compliance has put an upper limit on nitrogen and phosphorous use.

Mark Tucker of Yara told the conference that nutrition is no less important today, but that growers need to focus on many other factors also to get a balance in overall nutrition on worn tillage ground.

Mark pointed out that three different world record yield attempts in 2011, 2012 and 2013 produced wheat yields of 14.1t, 6.3t and 13.2t/ha respectively. All these crops received 320kg N/ha, but they did not convert the nutrient to yield for different reasons. And in 2015, new world records were established for winter wheat and oilseed rape of 16.52t/ha and 6.7t/ha respectively.

Both records focused heavily on crop nutrition, plus the use of organic manures, which tend to create an environment where the soil and crop can make better use of the applied artificial fertilisers.

Mark pointed to the need for nutrition in the context of risk management. A grower needs to produce a big crop for economic reasons, but this must be balanced against any increased costs for fertiliser, growth regulation and pest control. Crops need balanced nutrition and Mark pointed out that plants need 13 different nutrients. Any deficiency limits the use efficiency of all others. “Nutrients must be managed for optimum performance, but to manage, you need to measure,” Mark insisted.

He pointed to the fact that many soils do not have the optimum fertility to produce high yields. Lime status or pH is critical, but sub-clinical or non-visible deficiencies can be the biggest yield robber. Identification of problems requires both soil and foliar analysis and he pointed to the need to prevent deficiency symptoms from establishing.

Phosphorous fertilisation is very important and many soils are sub-optimum. Cold and wet pose additional availability challenges. He stated that foliar-applied phosphate is a good source of P and that this should not be confused with foliar phosphite.

Potassium is also very important, especially during peak growth periods in spring. Daily requirement can be as high as 6kg to 11kg K/ha during peak uptake between March and May.

Sulphur is important to help nitrogen use efficiency. Zinc plays an important role in the plant’s natural defence mechanisms and so might even be considered in the autumn on some crops. Zinc also improves nitrogen use efficiency.

Breaking out of the yield plateau

Faced with the challenge of flat yields for many years, Jake Freestone from Overbury Farms, located on the border of Worcestershire and Gloucestershire in England, dedicated his Nuffield travel scholarship to learning the fundamentals of soil care in other parts of the world.

Zero tillage, cover crops, rotation and livestock have since become part of his farming system.

Given the challenges of increasing world population and the yield expectancy of 20t/ha 20 years from now, yield improvement on his farm needed to increase.

Soil improvement

His Nuffield experiences brought him to many farms which have been addressing these challenges for some time and they shared one common focus – soil improvement.

Improving the organic matter content of worn soils helps appearance, structure, nutrient availability and moisture retention.

All these things are beneficial for productivity and Jake brought home many changes, the first being zero till to keep residue on the surface.

With zero till came cover cropping to have something growing in the ground almost all of the time to help protect the soil.

If he can get a six-week window between winter crops, he will plant a cover crop immediately behind the combine to help hold moisture and minerals.

Minimal soil disturbance helps minimise weed germination and reduces the risk that soil will move in water that flows over the top.

Rotation is also part of the farm response. A good mixed rotation provides more marketing opportunities, coupled with decreased reliance on specific chemical families.

1,000 sheep

The final piece of the jigsaw is the use of livestock. He already had 1,000 sheep and he is now set to double this number. He aims to use the sheep to graze the cover crops.

Jake sees zero tillage as bringing the greatest benefit to his soil, followed by rotation. Then the cover crops and sheep combine to bring additional benefit.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: