Historically, seed treatments were developed as a way of controlling seed-borne diseases in cereals and enhancing the quality of the seed. Seed-borne diseases such as Bunt and Fusarium had a major effect on cereal production, so the control of these diseases was a fundamental challenge.

Primitive treatments such as salt water and copper sulphate were used up until the discovery of compounds in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that were more effective and less troublesome to apply.

Seed treatments have been developing continuously since then to reflect disease pressure and, more recently, health and safety concerns. The need for treatments evolved in response to changing disease and insect pressure imposed by nature, evolving producing systems and the intensification of production.

In the 1970s and 80s, the predominant seed treatment used was a combination of a mercury compound and the insecticide, Lindane.

Brand names such as Panogen and Kotol might be familiar to older readers. Mercury was a very effective fungicide controlling a broad range of the common traditional seed borne diseases. Lindane was an insecticide that was primarily used to control wireworm attack, which was common when cereals and other crops were rotated with old grassland. Lindane also had the hugely useful side effect of being a serious bird repellent.

This combination of products gave excellent seed-borne disease control and the Lindane allowed growers to sow crops at the extremities of the season without having to worry about crow attacks.

Later in this period, there was a level of usage of specific fungicide treatments which were used for the control of specific diseases such as loose smut and also seedling mildew. Products such as Ferrax, Sapron, and Baytan were among those used.

The mercury vacuum

The use of mercury-based treatments was discontinued when concern developed over their toxicity to man and animals within the environment. Systemic fungicides used for plant protection were developed into commercial formulations for use as seed dressings. Products such as Guazatine, Flutriafol and Imazalil were marketed.

Brand names such as Panoctine, Panoctine plus, Rappor, Rappor plus, Raxil, Fungazil and Vincit will be familiar to growers from the 1990s. These products had varying degrees of efficacy on the different seed-borne diseases and were not as effective across the board as the old mercury based products.

A particularly wet season in 1991 led to high levels of Fusarium infection in the seed. This resulted in subsequent problems in crops where the dressings which were applied had varying levels of success in controlling this disease.

These problems brought about the realisation that treatments applied had to be appropriate for the pathology requirements of the seed.

Seed treatment application technology is improving with newer machines capable of giving better coverage of the pesticides on the seed and increasing the efficacy of the treatments

The day of one general dressing controlling all seed problems has gone. Best practice now involves the sampling of individual seed lots for disease followed by the application of the most appropriate treatment for the infections at the level present.

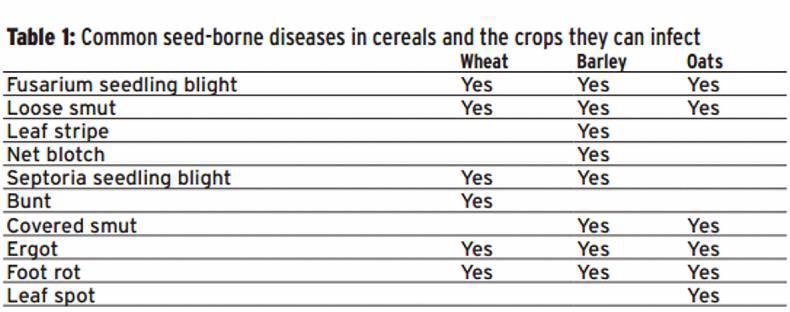

Likely soil-borne infections and disease control in seedling plants are also catered for by various dressings. Common seed-borne diseases are shown in Table 1.

In the year 2000, the EU took a decision to ban Lindane use because of health concerns. This decision had a major impact in Ireland. Lindane was used for wireworm control but it is hard to claim that wireworm damage was a significant problem in older tillage rotations. However, Lindane was very effective at repelling bird feeding in hungry times and its use allowed us to extend the cereal-sowing season despite our high population of hungry crows.

In Ireland, crops sown late in the autumn or early in the spring, especially in isolation, were particularly prone to bird attack and there were significant establishment losses where birds could not be controlled. The ban on Lindane effectively curtailed the late planting of winter wheat and early sowing of spring cereals.

Current actives

The most common single purpose dressings in use currently are Anchor (Thiram and Carboxin) and Kinto (Triticonazole and Prochloraz).

A significant breakthrough occurred when Bayer developed the addition of an insecticide to the fungicide treatment. Their product, Redigo Deter, not only controls seed-borne diseases, but it also mitigates against aphid attack which helps to prevent barley yellow dwarf virus (BYDV) in winter crops. A significant number of growers now use this treatment as an aid in the control of BYDV, especially in early-planted crops and in high risk areas. A list of the products registered for use on cereals in Ireland is shown in Table 2.

Many of these products contain actives that are or were used widely as fungicides for foliar disease control. The contents of all of the products registered for use on the three main cereals in Ireland are shown in Table 3, but many of these are not used commercially, as indicated in Tables 2 and 3.

It is worth noting that other products and actives can be used on seed. However, this is providing they are registered elsewhere in the EU and that they are already applied to the seed at the point of seed import.

Other dressings

Seed treatments are also being used to overcome rotational and nutritional constraints for cereal crops. Take-all is a disease that can have a significant effect on cereal crops, especially wheat. It is usually associated with the rotation but it can be exacerbated by soil type and by wet winter weather in particular. Latitude, a seed applied treatment marketed by Monsanto, helps to overcome this disease allowing the crop to be grown where it would otherwise be vulnerable to Take-all attack.

Various combinations of trace and major elements are also available as seed dressings to ensure that germinating seeds get essential nutrition, especially where there is the possibility of deficiency. Products containing manganese, zinc, magnesium and phosphate are available and used. Complex treatments are not unusual either, with up to three products being applied.

However, I would suggest some basic pointers when considering what treatments to apply because we require them to perform key functions and they add a significant additional cost.

Test seed to identify the infections present.Be aware of potential soil deficiencies.Ensure products are applied accurately.Ensure manufacturers label recommendations are adhered to.Be aware that different treatments can affect flow rate of seed in the drill. Calibrate drill for different treatments.Be aware that some treatments can delay germination and emergence.If you require additional seed treatments over and above the basic, it is important that such specific seed orders are placed well in advance of intended use so as to give the processor time to get the seed dressed and avoid unnecessary planting delays.

Developments in seed treatment

As legislation on health and safety becomes more stringent and consumer perceptions about pesticides become even more acute, it is likely that seed treatments will become more important as a vehicle to enhance the health of seeds and ensure viable and economically successful crops.

In the future, we are likely to see the development of more persistent and effective seed treatments, as the use of foliar-applied pesticides becomes more regulated with many active substances already removed from the EU market. The concept of applying minute volumes of pesticides to the seed, instead of applying litres of active ingredients to the crop, makes absolute sense from an environmental perspective.

Seed treatment application technology is also improving with the newer machines capable of giving better coverage of the pesticides on the seed and, thus, increasing the efficacy of the treatments.

Seed coatings are common on other seed species and these are likely to be used on cereal seed in the future. The big advantage will be better persistence of the chemical and a consistent size of seed, which will also improve the accuracy of seeding.

Key points

Seed-borne diseases were a problem in the past and could again become a serious problem unless seed is treated with the necessary care. Diseases such as loose smut on barley or bunt on wheat can silently devastate a crop and only become evident during grain fill.Diseases such as leaf stripe can completely devastate a barley crop at the grass-corn stage.Seed dressings should be applied that are appropriate to the needs of each individual seed lot. Read more

To read the full Certified Seed Focus Supplement, click here.

Historically, seed treatments were developed as a way of controlling seed-borne diseases in cereals and enhancing the quality of the seed. Seed-borne diseases such as Bunt and Fusarium had a major effect on cereal production, so the control of these diseases was a fundamental challenge.

Primitive treatments such as salt water and copper sulphate were used up until the discovery of compounds in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that were more effective and less troublesome to apply.

Seed treatments have been developing continuously since then to reflect disease pressure and, more recently, health and safety concerns. The need for treatments evolved in response to changing disease and insect pressure imposed by nature, evolving producing systems and the intensification of production.

In the 1970s and 80s, the predominant seed treatment used was a combination of a mercury compound and the insecticide, Lindane.

Brand names such as Panogen and Kotol might be familiar to older readers. Mercury was a very effective fungicide controlling a broad range of the common traditional seed borne diseases. Lindane was an insecticide that was primarily used to control wireworm attack, which was common when cereals and other crops were rotated with old grassland. Lindane also had the hugely useful side effect of being a serious bird repellent.

This combination of products gave excellent seed-borne disease control and the Lindane allowed growers to sow crops at the extremities of the season without having to worry about crow attacks.

Later in this period, there was a level of usage of specific fungicide treatments which were used for the control of specific diseases such as loose smut and also seedling mildew. Products such as Ferrax, Sapron, and Baytan were among those used.

The mercury vacuum

The use of mercury-based treatments was discontinued when concern developed over their toxicity to man and animals within the environment. Systemic fungicides used for plant protection were developed into commercial formulations for use as seed dressings. Products such as Guazatine, Flutriafol and Imazalil were marketed.

Brand names such as Panoctine, Panoctine plus, Rappor, Rappor plus, Raxil, Fungazil and Vincit will be familiar to growers from the 1990s. These products had varying degrees of efficacy on the different seed-borne diseases and were not as effective across the board as the old mercury based products.

A particularly wet season in 1991 led to high levels of Fusarium infection in the seed. This resulted in subsequent problems in crops where the dressings which were applied had varying levels of success in controlling this disease.

These problems brought about the realisation that treatments applied had to be appropriate for the pathology requirements of the seed.

Seed treatment application technology is improving with newer machines capable of giving better coverage of the pesticides on the seed and increasing the efficacy of the treatments

The day of one general dressing controlling all seed problems has gone. Best practice now involves the sampling of individual seed lots for disease followed by the application of the most appropriate treatment for the infections at the level present.

Likely soil-borne infections and disease control in seedling plants are also catered for by various dressings. Common seed-borne diseases are shown in Table 1.

In the year 2000, the EU took a decision to ban Lindane use because of health concerns. This decision had a major impact in Ireland. Lindane was used for wireworm control but it is hard to claim that wireworm damage was a significant problem in older tillage rotations. However, Lindane was very effective at repelling bird feeding in hungry times and its use allowed us to extend the cereal-sowing season despite our high population of hungry crows.

In Ireland, crops sown late in the autumn or early in the spring, especially in isolation, were particularly prone to bird attack and there were significant establishment losses where birds could not be controlled. The ban on Lindane effectively curtailed the late planting of winter wheat and early sowing of spring cereals.

Current actives

The most common single purpose dressings in use currently are Anchor (Thiram and Carboxin) and Kinto (Triticonazole and Prochloraz).

A significant breakthrough occurred when Bayer developed the addition of an insecticide to the fungicide treatment. Their product, Redigo Deter, not only controls seed-borne diseases, but it also mitigates against aphid attack which helps to prevent barley yellow dwarf virus (BYDV) in winter crops. A significant number of growers now use this treatment as an aid in the control of BYDV, especially in early-planted crops and in high risk areas. A list of the products registered for use on cereals in Ireland is shown in Table 2.

Many of these products contain actives that are or were used widely as fungicides for foliar disease control. The contents of all of the products registered for use on the three main cereals in Ireland are shown in Table 3, but many of these are not used commercially, as indicated in Tables 2 and 3.

It is worth noting that other products and actives can be used on seed. However, this is providing they are registered elsewhere in the EU and that they are already applied to the seed at the point of seed import.

Other dressings

Seed treatments are also being used to overcome rotational and nutritional constraints for cereal crops. Take-all is a disease that can have a significant effect on cereal crops, especially wheat. It is usually associated with the rotation but it can be exacerbated by soil type and by wet winter weather in particular. Latitude, a seed applied treatment marketed by Monsanto, helps to overcome this disease allowing the crop to be grown where it would otherwise be vulnerable to Take-all attack.

Various combinations of trace and major elements are also available as seed dressings to ensure that germinating seeds get essential nutrition, especially where there is the possibility of deficiency. Products containing manganese, zinc, magnesium and phosphate are available and used. Complex treatments are not unusual either, with up to three products being applied.

However, I would suggest some basic pointers when considering what treatments to apply because we require them to perform key functions and they add a significant additional cost.

Test seed to identify the infections present.Be aware of potential soil deficiencies.Ensure products are applied accurately.Ensure manufacturers label recommendations are adhered to.Be aware that different treatments can affect flow rate of seed in the drill. Calibrate drill for different treatments.Be aware that some treatments can delay germination and emergence.If you require additional seed treatments over and above the basic, it is important that such specific seed orders are placed well in advance of intended use so as to give the processor time to get the seed dressed and avoid unnecessary planting delays.

Developments in seed treatment

As legislation on health and safety becomes more stringent and consumer perceptions about pesticides become even more acute, it is likely that seed treatments will become more important as a vehicle to enhance the health of seeds and ensure viable and economically successful crops.

In the future, we are likely to see the development of more persistent and effective seed treatments, as the use of foliar-applied pesticides becomes more regulated with many active substances already removed from the EU market. The concept of applying minute volumes of pesticides to the seed, instead of applying litres of active ingredients to the crop, makes absolute sense from an environmental perspective.

Seed treatment application technology is also improving with the newer machines capable of giving better coverage of the pesticides on the seed and, thus, increasing the efficacy of the treatments.

Seed coatings are common on other seed species and these are likely to be used on cereal seed in the future. The big advantage will be better persistence of the chemical and a consistent size of seed, which will also improve the accuracy of seeding.

Key points

Seed-borne diseases were a problem in the past and could again become a serious problem unless seed is treated with the necessary care. Diseases such as loose smut on barley or bunt on wheat can silently devastate a crop and only become evident during grain fill.Diseases such as leaf stripe can completely devastate a barley crop at the grass-corn stage.Seed dressings should be applied that are appropriate to the needs of each individual seed lot. Read more

To read the full Certified Seed Focus Supplement, click here.

SHARING OPTIONS