I had the opportunity, along with colleagues, to visit Brazil and Uruguay in recent weeks to examine their agricultural development plans and their research and advisory systems. Anyone who visits Brazil must be gobsmacked by the scale of the country in every aspect.

On another occasion, I hope to set out their most impressive research infrastructure. Suffice it to say here that there seems to be no shortage of money for research. Embrapa, the state agriculture research body, spends about US$1bn per annum and employs around 10,000 — about 10 times that of Teagasc and over 16 times our research staff.

There seems to be no let-up in investment and government commitment to the public research sector. We saw a newly completed agro-energy complex at Embrapa’s HQ which must have cost €15m to €20m to complete.

Everyone is aware of Brazil’s beef sector but what was really impressive were the strides made by its dairy industry. They are not exporting yet but self-sufficiency has risen to 97% in milk products and it is only a matter of time before they enter the export market. Production has been growing at over 9% per year over the last 15 years. Cow numbers are driving production at a rate of about 6.4% per year and yields are growing at 2.8%.

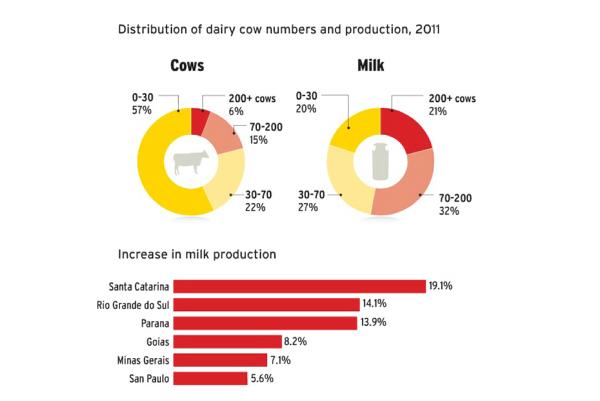

Brazil has about 1.1 million dairy farms. This number has declined from over 1.8 million in 1996 or a rate of decline of over 3% per year. The country has a staggering 23 million plus dairy cows which is up about seven million on the 1996 level. The estimated distribution of cow numbers and production is shown in the graphic (right).

A little over 50% of the milk comes from about 20% of the cows and these are on about 10% of farms. Around 6,000 farms with over 200 cows account for more than 20% of production. Herds are definitely getting bigger and concentrated on fewer farms but there are few big factory operations.

||PIC2||

We were surprised that the farming system which is being advocated is clearly grass-based. The pre-dominant grass is the tropical Bracharia variety, which grows very rapidly but has a low digestbility. They don’t practise rotational grazing but they’re very attentive to the persistence of the crop.

Everywhere in Brazil, we heard concerns expressed about the problem of degraded pastures. A sophisticated crop rotation system is recommended by Embrapa, together with reseeding every five years, or so. But it is difficult to get farmers to adopt these recommendations.

They’re also pushing the use of crossbred cows involving a cross between the Gir of Indian origin and the Holstein. This is a sturdy animal capable of withstanding the stresses of a very demanding climate and environment.

||PIC3||

The emphasis on low cost grass and breed of animal clearly mirrors our own preferred system. It was clear from talking to Embrapa researchers that they were committed to this system as their preferred model. This preference was also influenced by growing concerns about sustainability. We found little support for the stall-fed Holstein system.

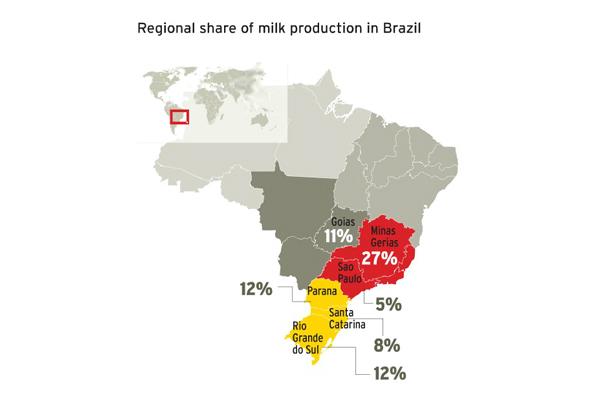

The accompanying map shows the main milk producing regions of Brazil. The south, comprising the states Santa Catarina, Rio Grande do Sul and Parana, accounts for 32% of overall production of milk and each state contributes a roughly equal share. The south east, comprising the states of Minas Gerais and Goias, accounts over 43% of the total milk with Minas Gerais contributing over 27% of this total.

||PIC4||

What’s really notable, however, is the growth of production across the states. The growth rate is impressive for all states but especially in the south which enjoys a more temperate climate better suited to pasture systems.

What about the economics of production? We were surprised in both Brazil and Uruguay to find such little emphasis placed on, or in-depth knowledge of, the economics of production. We put this down to the relative absence in both countries of an advisory service.

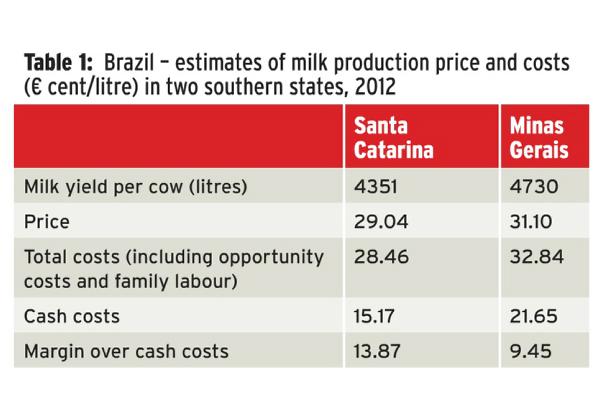

I did, however, manage to get some production costs and returns for typical dairy farms for two of the states in the south, namely, Santa Catarina and Minas Gerais (Table 1).

If you compare these results with the middle band of milk producers from last year’s (an admittedly poor year) Teagasc e-Profit Monitor, some interesting features emerge. Milk prices on the ePM farms were over 3.5c higher in Ireland than in the state of Santa Catarina but only about 1.5c higher than in Minas Gerais. It’s not really possible to compare total costs from the ePM and the Brazilian data but cash costs should be roughly comparable.

||PIC5||

Cash costs in Ireland were nearly 5.5c higher for the middle band of Irish dairy farmers compared with Santa Cartarina but over 1c/litre lower relative to the state of Minas Gerais. The margin over cash costs for Irish middle-ranking producers was about 2c/litre behind Santa Catarina but well over 2.5c greater than Minas Gerais. Yields were about 700 and 300 litres greater in Ireland than in Santa Carina and Minas Gerais, respectively.

Of course, the top ePM farms enjoyed higher margins than Santa Catarina but cash costs were also higher.

||PIC6||

Of course, neither Brazilian or Uruguayan dairy farmers, unlike their Irish counterparts, have to comply with expensive environmental restrictions. There is no requirement for effluent storage for instance and we saw plenty of evidence of severe poaching in paddocks around the milking parlours. It is only a matter of time before these countries will have to ‘catch up’ with European practices as far as environmental controls are concerned.

Nonetheless, it’s apparent that milk production in the southern state of Santa Catarina is quite competitive with Ireland. It’s probably not surprising therefore that overall production in the state has been growing at an annual rate of close to 20%.

||PIC7||

There is no doubt that technology, good milk production conditions and good farmers are driving the rapid expansion in milk production in the southern states and especially in Santa Catarina. Farmers are increasingly using crossbred animals (Holstein x Gir) to improve yields. Yields were also growing due to the deployment of more sophisticated crop rotations and much higher yielding maize feed.

The stamp of the massive public investment in research is clearly beginning to pay off in milk production as well as in cropping.

Milk production in Brazil is worth keeping in our sights.

* I’d like to thank Tom Kelly and Frank O’Mara, who accompanied me on the trip, for their comments.

SHARING OPTIONS