Husk separation on barley, or skinning as we know it, was a serious issue for malting barley growers in 2016. This may not have been the first time that this problem occurred but it was serious in 2016 because, for the first time, it resulted in substantial rejection of samples for malting and, with it, the loss of the premium on a substantial proportion of the crop.

The problem is not unique to Ireland or to 2016. Scottish growers encountered the same problem in recent years and researchers there have been looking at the likely causes of the problem.

Getting to grips with its cause and likely prevalence is more difficult. It seems that it can occur any year, but it doesn’t always. Most modern varieties are prone to husk damage but some may be more susceptible to damage than others.

It seems that the characteristic is more prevalent in modern higher-yielding varieties that have been bred for improved malting, brewing or distilling characteristics.

However, given the nature of modern plant breeding, where the major focus is for malting but some do not meet all the criteria, it is hardly surprising that skinning can also occur in feed varieties.

One must ask if bigger grains and better grain fill could be a contributory factor? That aside, the problems is ultimately a result of the failure of the glue that sticks the husk onto the germ of the grain.

Review of the factors

Skinning was one of the topics discussed at the recent Teagasc malting barley seminars. A review paper was to be presented by Steve Hoad from SRUC in Scotland but unfortunately he was not able to attend. However, his presentation was ably delivered by Ciaran Collins of Teagasc.

Skinning in barley is when the husk becomes detached from the underlying caryopsis or what we might call the germ of the grain. To understand what happens it is necessary to go back to the flowering stage of the crop.

At flowering, the individual ovary in each flower or grain site is fertilised by the pollen and from that point it begins to swell, fill and expand. After it reaches full size and, somewhere around the early dough stage between 18 and 23 days post-flowering, the husk begins to adhere to the caryopsis or swollen ovary. It has been expanding up to this point so adhesion is not possible before this. This adhesion is done by a naturally produced glue-type substance technically referred to as cement and sometimes referred to as the bubbly layer.

Growth conditions appear to be important during this critical adherence phase. The presentation indicated that high humidity and low sunlight levels during this phase can affect the cementing process which adheres the germ to the husk. Some also suggest that other stress issues such as deficiencies may also impact negatively on the formation of the cement layer.

From this presentation one might form the opinion that the better the growing conditions during grain fill the better the quality of the cement produced and, possibly, the less likely skinning will be a problem. However, this was not suggested to be the situation as another major factor is also at play.

A second predisposing factor to skinning is alternating wetting and drying conditions during grain ripening. Growers will be aware of this and it basically means that the risk is increased the longer it takes to get ripe crops harvested and off the land. The cause of the deterioration of the cement layer was not given but it may be as simple as wetting and drying effectively dissolving or weakening the cement layer.

What is less certain is whether these two predisposing factors are connected. If we got really good conditions during the adhesion phase at the early dough stage might we still get significant problems with alternating wet and dry conditions during grain ripening? Or if we had poor conditions for cement formation at the early dough stage might we still not see husk detachment in the lead-up to a warm continuously dry harvest?

Predisposing factors

As stated previously, the husk is adhered to the caryopsis or germ by the cement layer using a cement/glue-type substance that binds the husk to the caryopsis or kernel or germ of the seed. Steve’s presentation indicated that the presence of grain skinning can lead to:

Loss of malting efficiency with lower malt production.The commercial failure of a variety with losses for the breeder’s investment. Rejection of loads by the maltster leading to loss of premium for growers.One can add to these the huge frustration felt by growers in having to deal with a problem that they can do nothing about. But one must also say that this was a huge problem for the maltsters who had to reject barley from growers and then import barley.

Ciaran’s presentation showed that Scottish trials were inconclusive with regard to the impact of plant growth regulator use on skinning but there seemed to be a clear trend that very high nitrogen rates appeared to result in higher skinning levels in some but not all varieties. Might this be a physiologcal consequence or might it simply relate to bigger grain fill from prolonged growth?

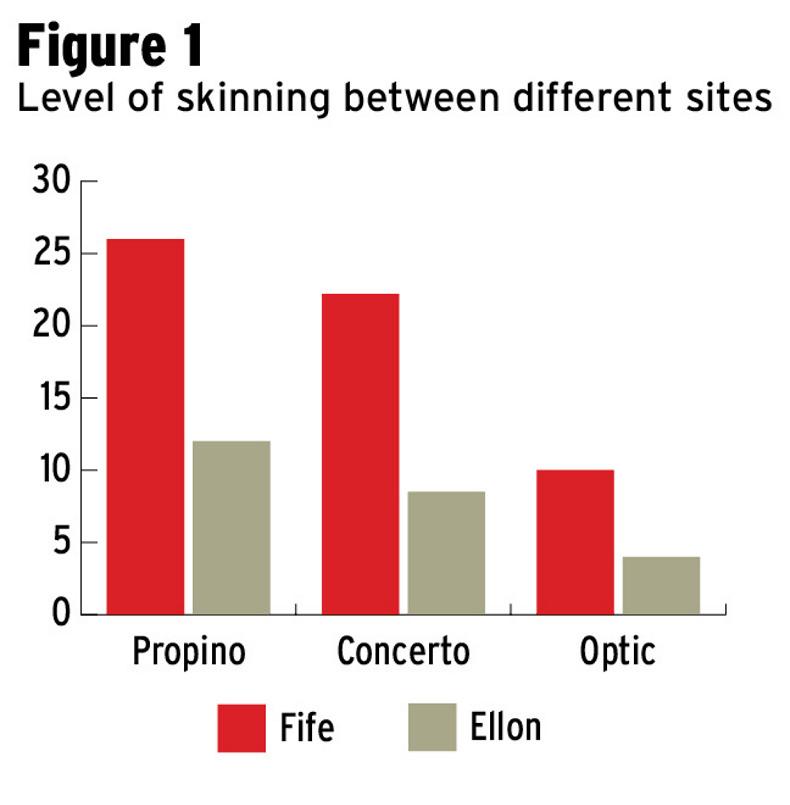

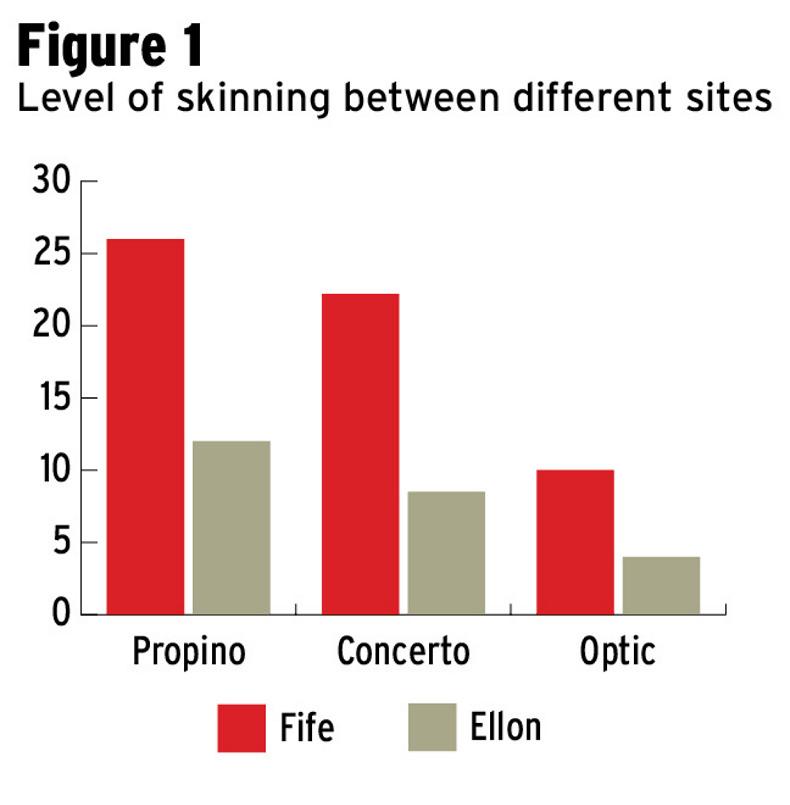

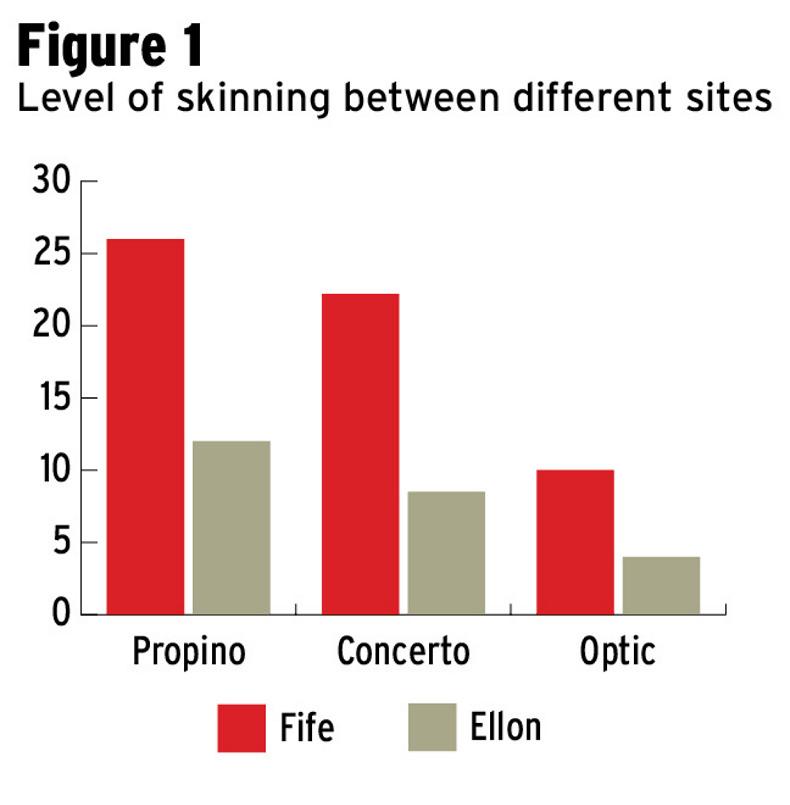

Scottish work showed a variety effect but this might not always be sufficient to prevent rejection. Trials showed variety differences to be similar at different sites (best was best and worst was worst) but the level of skinning could still be significantly different between sites (see Figure 1).

In other trials in 2012 and 2013, the year effect was very evident with regard to the level of skinning found. In these two years, there was a visible but less than conclusive effect of early and late planting and harvesting on the level of skinning found.

The problem was that individual varieties responded differently in different years. But the advice will rightly point to planting as early as is practically possible as an effort to to help reduce the risk of skinning.

The effect of concave clearance and drum speed setting were also clearly shown in Scottish research. However, the level of damage encountered depended significantly on whether a variety was regarded as susceptible or resistant to skinning. The ones that were less prone showed less damage regardless of concave setting or drum speed compared with the varieties regarded as being more susceptible to skinning damage.

Reduced malting efficiency

Research that examined the consequence of skinning on malting efficiency showed that when the level of skinning went above 50% the hot water extract levels fell. The presence of skinned grains allows for differential uptake of water into individual grains during the malting process and this can therefore affect the efficiency of the malting process.

The next problem arises during the alcohol formation stages. Many processors operate a system which uses the husk of the grain to create a natural filter bed through which the alcohol/liquid is drained. This is especially important in processing plants that use a Lauter tun.

When this natural filter is changed in any way it can either speed up or slow down the filtration process and the filtering period. So having insufficient husk could mean insufficient filtration as the husk actually creates the filter for the liquid that drains off the mash in systems that use this technique. And insufficient filtration could mean that compounds get through into the distilling process that can give rise to undesirable flavours or consequences.

Assessing damage

One of the early challenges that faced the Scottish researchers was to be able to describe and quantify different levels of skinning. Early assessments showed that different operators in differnt laboratories recorded very different levels of skinning in test samples. They developed a descriptive key, which they hoped could be a universal key, to characterise a sample relative to the amount of skinning present. This involved fixed sample sizes with a given amount of grain to be assessed per sample alongside a definite sampling protocol. This was then tested across laboratories and technicians and it ultimately proved to be quite robust in the repeatability of the results produced.

This Scottish skinning evaluation process assesses skinning on the basis of four grades of damage:

A. < 20% skinning. This is regarded as not skinned. It generally refers to the skin removed near the tip of the grain where some of the skin peeled off in the efforts to complete awn removal.

B. >=20% – <50% skinning.

C. >=50% – <100% skinning.

D. 100% skinned (This can be referred to as pearled barley.)

The researchers tested this key with a number of institutions and found that it had relatively good consistency and repeatability across users. Following this research the key was deemed fit for purpose at farm and merchant level.

Hopefully this assessment method can be used to evaluate samples quickly at the weighbridge and that it represents the real risk to the upstream processors. It would seem to offer a potentially robust assessment of the level of skinning present in a sample but we are not told about the size of sample that was used or how long it might take to carry out the test at the weighbridge.

Damage to the skin of malting barley can result in differential performance between individual grains during malting.The absence of the husk can impact on processing as it may result in inadequate filtration. Adherence of the husk can be influenced by weather during the dough stage of grain fill and wetting and drying prior to harvest. Read more

Septoria resistance threat is very real

Husk separation on barley, or skinning as we know it, was a serious issue for malting barley growers in 2016. This may not have been the first time that this problem occurred but it was serious in 2016 because, for the first time, it resulted in substantial rejection of samples for malting and, with it, the loss of the premium on a substantial proportion of the crop.

The problem is not unique to Ireland or to 2016. Scottish growers encountered the same problem in recent years and researchers there have been looking at the likely causes of the problem.

Getting to grips with its cause and likely prevalence is more difficult. It seems that it can occur any year, but it doesn’t always. Most modern varieties are prone to husk damage but some may be more susceptible to damage than others.

It seems that the characteristic is more prevalent in modern higher-yielding varieties that have been bred for improved malting, brewing or distilling characteristics.

However, given the nature of modern plant breeding, where the major focus is for malting but some do not meet all the criteria, it is hardly surprising that skinning can also occur in feed varieties.

One must ask if bigger grains and better grain fill could be a contributory factor? That aside, the problems is ultimately a result of the failure of the glue that sticks the husk onto the germ of the grain.

Review of the factors

Skinning was one of the topics discussed at the recent Teagasc malting barley seminars. A review paper was to be presented by Steve Hoad from SRUC in Scotland but unfortunately he was not able to attend. However, his presentation was ably delivered by Ciaran Collins of Teagasc.

Skinning in barley is when the husk becomes detached from the underlying caryopsis or what we might call the germ of the grain. To understand what happens it is necessary to go back to the flowering stage of the crop.

At flowering, the individual ovary in each flower or grain site is fertilised by the pollen and from that point it begins to swell, fill and expand. After it reaches full size and, somewhere around the early dough stage between 18 and 23 days post-flowering, the husk begins to adhere to the caryopsis or swollen ovary. It has been expanding up to this point so adhesion is not possible before this. This adhesion is done by a naturally produced glue-type substance technically referred to as cement and sometimes referred to as the bubbly layer.

Growth conditions appear to be important during this critical adherence phase. The presentation indicated that high humidity and low sunlight levels during this phase can affect the cementing process which adheres the germ to the husk. Some also suggest that other stress issues such as deficiencies may also impact negatively on the formation of the cement layer.

From this presentation one might form the opinion that the better the growing conditions during grain fill the better the quality of the cement produced and, possibly, the less likely skinning will be a problem. However, this was not suggested to be the situation as another major factor is also at play.

A second predisposing factor to skinning is alternating wetting and drying conditions during grain ripening. Growers will be aware of this and it basically means that the risk is increased the longer it takes to get ripe crops harvested and off the land. The cause of the deterioration of the cement layer was not given but it may be as simple as wetting and drying effectively dissolving or weakening the cement layer.

What is less certain is whether these two predisposing factors are connected. If we got really good conditions during the adhesion phase at the early dough stage might we still get significant problems with alternating wet and dry conditions during grain ripening? Or if we had poor conditions for cement formation at the early dough stage might we still not see husk detachment in the lead-up to a warm continuously dry harvest?

Predisposing factors

As stated previously, the husk is adhered to the caryopsis or germ by the cement layer using a cement/glue-type substance that binds the husk to the caryopsis or kernel or germ of the seed. Steve’s presentation indicated that the presence of grain skinning can lead to:

Loss of malting efficiency with lower malt production.The commercial failure of a variety with losses for the breeder’s investment. Rejection of loads by the maltster leading to loss of premium for growers.One can add to these the huge frustration felt by growers in having to deal with a problem that they can do nothing about. But one must also say that this was a huge problem for the maltsters who had to reject barley from growers and then import barley.

Ciaran’s presentation showed that Scottish trials were inconclusive with regard to the impact of plant growth regulator use on skinning but there seemed to be a clear trend that very high nitrogen rates appeared to result in higher skinning levels in some but not all varieties. Might this be a physiologcal consequence or might it simply relate to bigger grain fill from prolonged growth?

Scottish work showed a variety effect but this might not always be sufficient to prevent rejection. Trials showed variety differences to be similar at different sites (best was best and worst was worst) but the level of skinning could still be significantly different between sites (see Figure 1).

In other trials in 2012 and 2013, the year effect was very evident with regard to the level of skinning found. In these two years, there was a visible but less than conclusive effect of early and late planting and harvesting on the level of skinning found.

The problem was that individual varieties responded differently in different years. But the advice will rightly point to planting as early as is practically possible as an effort to to help reduce the risk of skinning.

The effect of concave clearance and drum speed setting were also clearly shown in Scottish research. However, the level of damage encountered depended significantly on whether a variety was regarded as susceptible or resistant to skinning. The ones that were less prone showed less damage regardless of concave setting or drum speed compared with the varieties regarded as being more susceptible to skinning damage.

Reduced malting efficiency

Research that examined the consequence of skinning on malting efficiency showed that when the level of skinning went above 50% the hot water extract levels fell. The presence of skinned grains allows for differential uptake of water into individual grains during the malting process and this can therefore affect the efficiency of the malting process.

The next problem arises during the alcohol formation stages. Many processors operate a system which uses the husk of the grain to create a natural filter bed through which the alcohol/liquid is drained. This is especially important in processing plants that use a Lauter tun.

When this natural filter is changed in any way it can either speed up or slow down the filtration process and the filtering period. So having insufficient husk could mean insufficient filtration as the husk actually creates the filter for the liquid that drains off the mash in systems that use this technique. And insufficient filtration could mean that compounds get through into the distilling process that can give rise to undesirable flavours or consequences.

Assessing damage

One of the early challenges that faced the Scottish researchers was to be able to describe and quantify different levels of skinning. Early assessments showed that different operators in differnt laboratories recorded very different levels of skinning in test samples. They developed a descriptive key, which they hoped could be a universal key, to characterise a sample relative to the amount of skinning present. This involved fixed sample sizes with a given amount of grain to be assessed per sample alongside a definite sampling protocol. This was then tested across laboratories and technicians and it ultimately proved to be quite robust in the repeatability of the results produced.

This Scottish skinning evaluation process assesses skinning on the basis of four grades of damage:

A. < 20% skinning. This is regarded as not skinned. It generally refers to the skin removed near the tip of the grain where some of the skin peeled off in the efforts to complete awn removal.

B. >=20% – <50% skinning.

C. >=50% – <100% skinning.

D. 100% skinned (This can be referred to as pearled barley.)

The researchers tested this key with a number of institutions and found that it had relatively good consistency and repeatability across users. Following this research the key was deemed fit for purpose at farm and merchant level.

Hopefully this assessment method can be used to evaluate samples quickly at the weighbridge and that it represents the real risk to the upstream processors. It would seem to offer a potentially robust assessment of the level of skinning present in a sample but we are not told about the size of sample that was used or how long it might take to carry out the test at the weighbridge.

Damage to the skin of malting barley can result in differential performance between individual grains during malting.The absence of the husk can impact on processing as it may result in inadequate filtration. Adherence of the husk can be influenced by weather during the dough stage of grain fill and wetting and drying prior to harvest. Read more

Septoria resistance threat is very real

SHARING OPTIONS