Conacre, 11-month system or short-term rental – call it what you want, but it was targeted by the agri-tax review as expected.

More than 40,000 farmers rent land in this way each year. Indecon, the consultants who carried out the independent report, even considered bringing in a levy/tax on farmers who want to remain renting land from year to year. The recommendations focused on carrots instead. Seven of the 12 new measures brought in are focused on making long-term leases more attractive. There are now bigger tax-free thresholds, longer terms for leases and lower costs to long-term leasing, all of which will help.

I want to focus on two key measures that will get many people to either transfer their land now, or move away from conacre altogether. The reason is that as well as allowing the active farmer improve the owner’s land over time, it will save the owner a lot of tax.

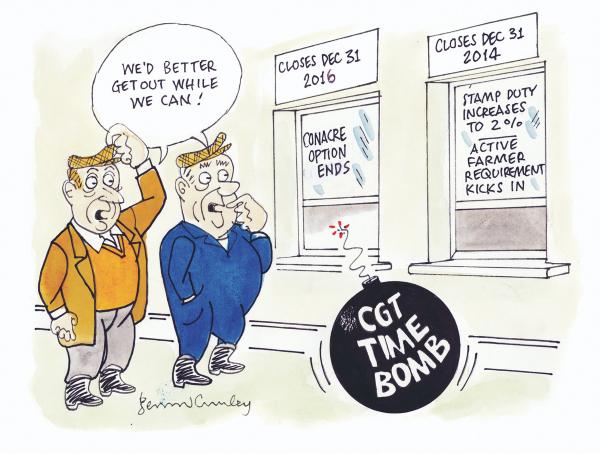

The biggest one is the once-off measure where land let on conacre will be eligible for retirement relief. It is open up until the end of 2016 mainly to ensure that farmers are not worried about making changes before CAP reform entitlements are established in 2015.

It is aimed at helping farmers who have found themselves in the conacre trap. This is where the farmer has stopped farming and started to rent his land out. In some cases they might have had a five-year lease initially but it finished and by default they moved to yearly rental.

As the farmer got older they might have thought about transferring the land. If they wanted to sell it or give it to someone other than their child they would not have been eligible for retirement relief. This mean they would have a massive tax bill, even when they were the ones handing over the asset.

Retirement relief can be hard to understand. It essentially means you don’t have to pay capital gains tax when you transfer or sell land that you have farmed yourself for 10 years and then started renting out. Most people do not know they would be liable for a tax bill if they give away an asset for free.

To explain, let’s look at an example of John, a farmer who is 76 and has been renting out his 50 acres on con-acre since he stopped farming 10 years ago. He inherited the land in the late 1970s and as has no children, he wanted to pass it on to his cousin. He even went to the accountant to do the sums. The land was put in at a cost of €1,500 an acre when he got it, but it is now valued at €11,000 an acre. His accountant worked out he would have a capital gain of €4,250/acre (indexation of 4.5 times brings up original price to €6,750), so he would have a capital gain on the transfer of €212,500. With the capital gains tax at 33%, he has a tax bill of just under €70,000. You can imagine the shock on his face and how quick he made the decision to keep the status quo. If he had leased the land on a long-term basis from the start he would have been eligible for retirement relief and the tax bill would be €0.

What this new measure does is give John is the opportunity to have no tax bill at all by allowing him to qualify for retirement relief if he either transfers the land before the end of 2016 or goes into a long-term lease of over five years before the deadline closes. It is a very generous measure that can save people like John up to €165,000 if their capital gain is up to €500,000. The one condition they have set is that you must have farmed the land yourself for 10 years before you first let it. It doesn’t matter how far back you started letting, as the 15 years (25 years now) since ceasing farming is not even looked at in these cases. So, if you are in the conacre trap, or know an elderly farmer who is, make sure he knows about this before the window closes.

Escaping the conacre trap

The second measure is the move to target agriculture relief at active farmers. This is another great measure in that it does not stop people getting tax relief, but cuts out the situation of someone working in, say, the US, inheriting the land, getting the 90% agricultural relief and just renting the land out on short-term lease. You must still pass the farmer test of having 80% of your assets as agricultural on the day you get the land. But now you must also be a full-time farmer or a qualified young farmer. You have three years from when you get the land to get qualifications. To qualify as a full-time farmer, you must spend no less than 50% of your normal working time farming the land. If you are not a full-time farmer or qualified young farmer, the only other option to get the relief is to lease the land out over five years. This measure comes in on 1 January 2015 so land could still be transferred before then to escape the new active farmer clause.

The pension myth

I also want to dispel the myth that the long-term leased incentives are no good to landowners who are on the State old-age pension. “Sure we are not making enough to pay any tax so how would we benefit,” is what I am often told. I asked the Department of Agriculture to crunch the figures, taking the Budget 2015 changes into account

They compared three situations in which the landowner was in receipt of the old-age contributory State pension of €12,000. The farmer has 50 acres (20.23ha) and a Single Farm Payment of €6,174 (€305/ha – the average SFP for cattle farmers). Taking the Teagasc average income from cattle farming, he would hold on to the SFP and his total income would be €18,439. Yes, he would have very little tax to pay. If he decided to rent out the land, we estimated that he would get €150/acre plus half the entitlement value under the new CAP reforms, giving him €210/acre.

This would give him a gross income of €22,433 including the pension. As the table shows, if he went for conacre, he would be left with €19,553, over €1,500 more than if he farmed it himself. However, if he went for a long-term lease, the tax incentive would mean he keeps €22,145 after tax. That’s over €4,100 more a year compared to farming it himself. Going for long-term lease over conacre gives him an additional €2,600 a year, or nearly €13,000 over the five years of the lease. The inclusion of EU entitlements in the tax-exempt leasing income contributes significantly to the difference.

Remember, the benefits would be even greater if the farmer did not hold on to his SFP when actively farming, like a lot of farmers. Choosing a long-term lease also means he is eligible for retirement relief if he wants to sell or transfer the land in the future.

Agri-Taxation Review: A positive outcome for farmers

When the Agri- Taxation Review was announced in 2013, it was feared that it was a sneaky way to cut agri-tax reliefs. One year on, it not only made a stronger case for the benefits of existing reliefs, but brought in 12 new measures that will have a major impact. Agriculture Minister Simon Coveney was right – there has never been such a comprehensive package announced.

The 280-page Indecon report gave the background to what was brought in, what might still be brought in and what was ruled out. From talking to the key Department of Agriculture staff involved, it is obvious that they and their colleagues in the Department of Finance had a deep understanding of the agricultural sector and the changes needed. They engaged well with the industry, taking on board the submissions and holding individual meetings with 21 specialist groups.

Overall aim

The overall aim was not to change the level of Exchequer support, but to maximise the benefits to the sector of the existing level, valued at €340m in total (see graph). The report included an additional €341m for administration costs, shadow costs to public funds and environmental costs associated with increased production, to bring total economic costs to €681m. However, with benefits measured at €790m, they get €1.16 back for each €1 spent – a good case for additional measures.

Capital allowances are by far the biggest tax measures farmer benefit from at €192m, or 57% of the total costs. Capital allowances are not exclusive to agriculture, with any business able to write down fixed assets or machinery costs, although in some cases at different rates. The Indecon research found that every €1m of capital allowances claimed increased gross output by €1.9m.

There was evidence to back up targeted measures for young trained farmers as they were found to have on average 12% higher output compared with untrained farmers. The report also highlighted that the output of farmers over 65 is typically between 4% and 7.1% lower than that of farmers who are under 65. It was estimated that every €1m spent on retirement relief from capital gains tax would yield €1.75m in additional agricultural output.

The report also recommended that a working group should oversee the implementation of the suggested measures and bring in more changes for Budget 2016.

The two main ones were to extend income averaging to forestry clear felling profit, and to allow sole traders to avail of the SEAI incentives for energy-efficient equipment.

The group is also looking more closely at bringing in a risk deposit scheme to further protect farmers against volatility and also the phased transfer model the IFA had developed.

Other recommendations in the report worth further study were to make income received from leasing by farmers exempt from calculation of certain State payments like medical cards and nursing home entitlements. A number of older farmers I talk to are concerned that leasing out land would see them lose their medical card when they might need it most.

Accelerated capital allowances for young farmers for the first five years in business was another interesting recommendation. The report said building and equipment should qualify for at least up to 50% in year one and 12.5% over the next four years. It could be restricted to the young farmer earning €50,000 or less per year, with a cap of up to €500,000. This is being done in Britain and State aid approval would be needed. Interestingly, the report also recommended a similar accelerated capital allowances for farm infrastructure, restricting it to farm roadways, fencing and underpasses.

Although outside the scope of the review the report highlighted that in France a farmer does not automatically receive a state pension at 65, but only when he officially retires from farming and the land is transferred. It is similar in Germany and Austria, where a farmer has to choose between state pension and direct payment when they reach retirement age.

There is still plenty of more scope to build on the agri-tax changes announced, especially now we know the cost-benefit ratio of tax measures are so good for the Exchequer.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: