Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) was around in Britain since the mid 1980s and was treated as an animal disease only, until UK health secretary Stephen Dorrell’s announcement on 20 March 1996 that BSE in cattle was “the most likely explanation” for a variant of the deadly Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD).

The brain condition, which normally appears in older people, had inexplicably affected 10 people under 42 years of age. The similarities with “mad cow disease” led scientists to the only possible conclusion: BSE was transmissible to humans.

![]()

Click on the image to read the archive

The European Commission imposed a worldwide ban on UK beef and products containing beef extracts and a major campaign got under way in Ireland to protect Irish beef markets.

The Irish Farmers Journal reported on 30 March 1996 that factories and marts were at a standstill in Northern Ireland, while throughput was down by 70% in the Republic.

Mass cull in the UK

The age of the animal was a key factor in the risk of transmission. In the edition of 6 April, it was reported that an estimated 4.6m cull animals over 30 months would be brought for incineration over a six-year period in the UK, with compensation estimated at around £400 per head. Specified offals from UK cattle under 30 months old, and all cattle over 30 months, were to be excluded from the human and animal food chains.

In a letter to the editor, Richard Deansy from Nenagh, Co Tipperary, made the case that Northern Ireland farmers should be granted a special status from the UK over the BSE debacle. “Northern Ireland has been the unfortunate victim of this whole affair,” he said.

On 20 April, Co Down beef farmer Ivan McKelvey appeared on the front page of the Irish Farmers Journal with some of his finished steers over 30 months that had been ruled out of any market, including intervention.

![]()

Click on the image to read the archive

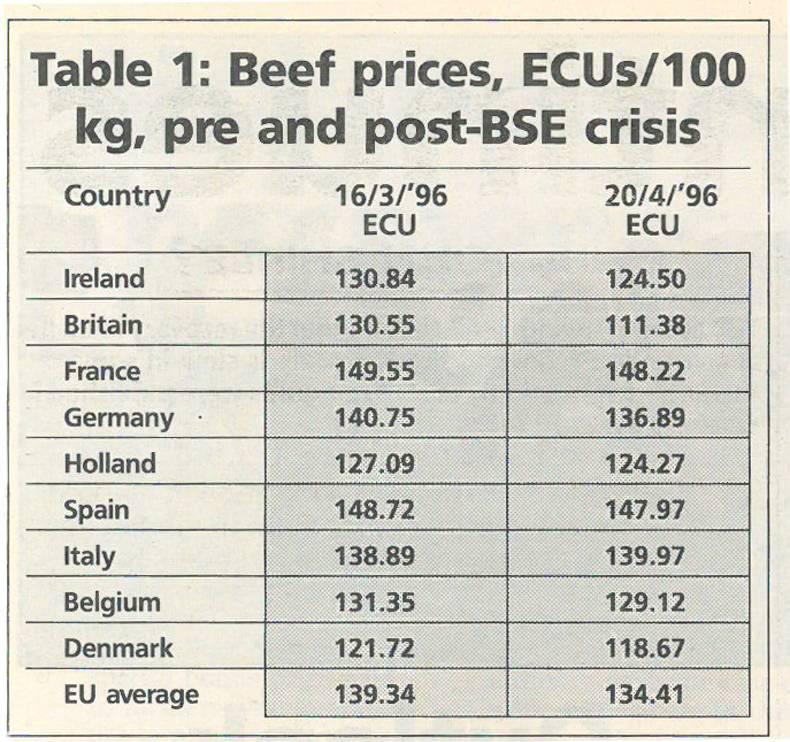

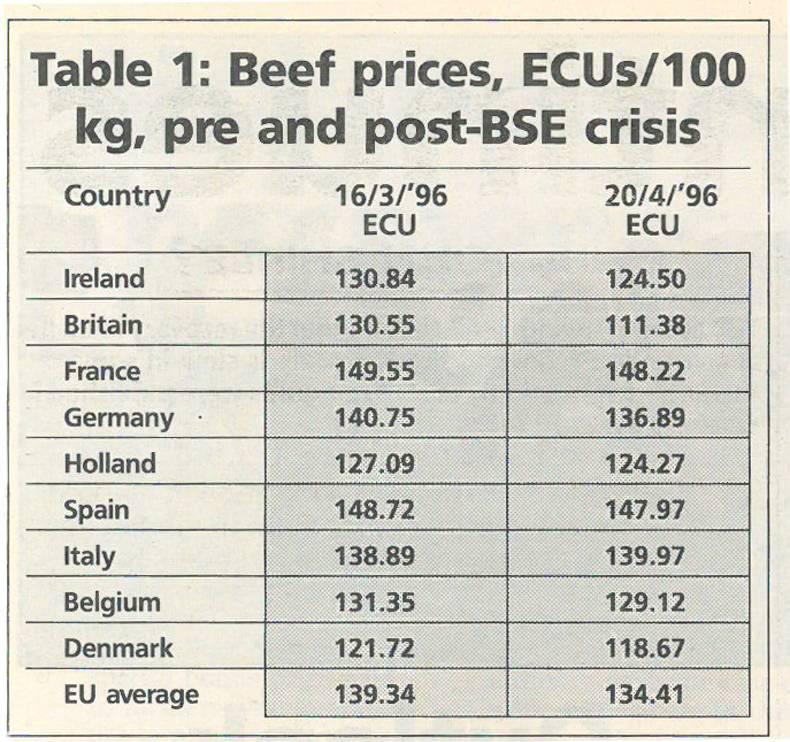

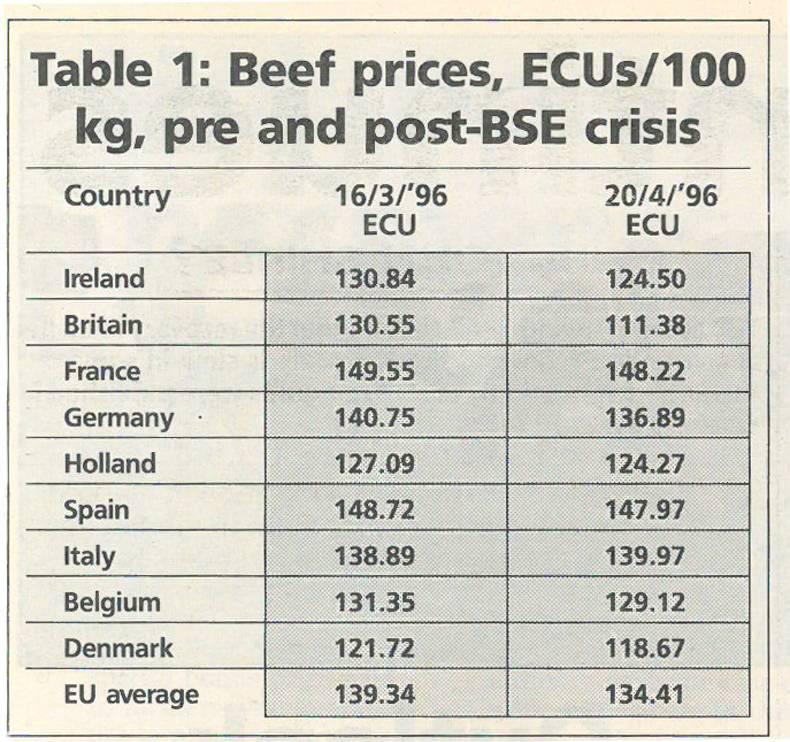

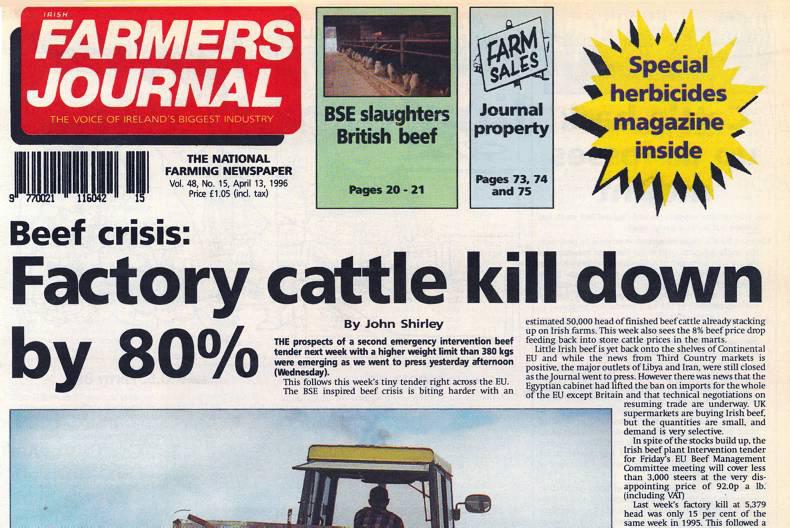

The previous week’s edition, on 13 April, carried the headline “Factory cattle kill down by 80%” with the news that 50,000 finished Irish cattle were stacking up on farms as Irish beef got caught up in the UK BSE scare.

Public confidence in beef was swept away in a tidal wave of fear and mistrust

Little Irish beef was reported to be on European supermarket shelves and many third country markets, such as Libya and Iran, remained closed. “Public confidence in beef was swept away in a tidal wave of fear and mistrust,” wrote David Allen.

The 20 April edition reported that consumption of local beef in continental Europe was down 20% and consumption of Irish beef was down as far as 80% in some regions. The following week, further figures from Bord Bia suggested that beef consumption in Ireland dropped by 30% at the height of the scare. In Germany the drop in consumption was the sharpest national decline across Europe at 70%, but this had started to recover.

In the third week of the over 30-month cattle disposal scheme in Northern Ireland, James Campbell reported on 25 May that 6,046 cattle had so far been incinerated. Around 54,000 cattle had been registered as over 30 months in NI. Some 18,000 of these were cows, meaning that 30,000 clean cattle were still to be destroyed. There were also 6,000 bulls between 24 and 30 months, which at the time did not qualify for intervention or the disposal scheme.

By 8 June 1996, Matt Dempsey’s editorial noted that the fallout from the BSE crisis had spread from the initial shock to winter finishers throughout the whole industry to hit cull cow, store cattle and even calf prices.

No real strategy

That week, European Commission president Jacques Santer said in Dublin that there was no real strategy to address the BSE scare two months on. In protest at politicians’ handling of a debate on the issue, IFA president John Donnelly led a walk-out of 100 livestock farmers from Dáil Éireann.

On 29 June, the Irish Farmers Journal reported that an EU compensation fund had been agreed, with around £70m assigned to Ireland. This was to be mostly in the form of top-ups for suckler cow and beef premiums.

![]()

Click on the image to read the archive

However, editor Matt Dempsey pointed out that this covered only around half of the financial losses to suckler farmers, and less than half for winter finishers. By 20 July, the compensation was known to be worth £22.40 on the suckler cow and £19.08 on the beef premium.

The real effect of the crisis on family farms was seen by 31 August 1996. The front-page reported that beef incomes were estimated to have dropped by 40% as the IFA protested outside Leinster House to highlight the poor Government response to the crisis.

Stricter EU regulation targeted the use of bovine meat and bone meal as a source of protein in cattle feed. The practice was the main source of BSE contamination across Europe and was already banned in Ireland since 1990.

Second scare in 2000

Four years later, on 4 November 2000, “BSE – a dying kick” was a headline in the Irish Farmers Journal as news broke that French cattle from farms where BSE cases were detected had entered the food chain. This hit consumer confidence again, as did revelations that meat and bone meal was still being fed to pigs and poultry and being mixed in the same feed mill as ruminant feed.

In his editorial on 11 November 2000, Matt Dempsey sensed the danger: “It may be – and hopefully is – too alarmist to say that a 1996 type panic is in danger of re-erupting but the signs at this stage are not encouraging.”

![]()

Click on the image to read the archive

Irish farmers pressed then Minister for Agriculture Joe Walsh for BSE testing of all cattle over 30 months to guarantee BSE-free Irish beef and secure export markets, as reported in the Irish Farmers Journal on 25 November 2000.

“Controlled-risk” status

By that time, meat and bone meal was banned as a feed for livestock and the incidence of BSE in cattle was falling. It would be 2006, however, before over-30-month cattle could enter the food chain again and the UK export ban would be lifted in other EU countries.

Work to end bans in other countries continues to this day. Both the UK and Ireland still have a “controlled-risk” BSE status, a level below the ideal “negligible risk” status. To achieve this, a country or region must have 11 years pass since the birth of the last infected animal. Northern Ireland now qualifies to apply for negligible risk status, while the Republic of Ireland had achieved it for a short period in June 2015 before a new case was found in Co Louth in May 2015.

Phelim O’Neill contributed reporting for this story.

Read more

Special feature: BSE 20 years on

Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) was around in Britain since the mid 1980s and was treated as an animal disease only, until UK health secretary Stephen Dorrell’s announcement on 20 March 1996 that BSE in cattle was “the most likely explanation” for a variant of the deadly Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD).

The brain condition, which normally appears in older people, had inexplicably affected 10 people under 42 years of age. The similarities with “mad cow disease” led scientists to the only possible conclusion: BSE was transmissible to humans.

![]()

Click on the image to read the archive

The European Commission imposed a worldwide ban on UK beef and products containing beef extracts and a major campaign got under way in Ireland to protect Irish beef markets.

The Irish Farmers Journal reported on 30 March 1996 that factories and marts were at a standstill in Northern Ireland, while throughput was down by 70% in the Republic.

Mass cull in the UK

The age of the animal was a key factor in the risk of transmission. In the edition of 6 April, it was reported that an estimated 4.6m cull animals over 30 months would be brought for incineration over a six-year period in the UK, with compensation estimated at around £400 per head. Specified offals from UK cattle under 30 months old, and all cattle over 30 months, were to be excluded from the human and animal food chains.

In a letter to the editor, Richard Deansy from Nenagh, Co Tipperary, made the case that Northern Ireland farmers should be granted a special status from the UK over the BSE debacle. “Northern Ireland has been the unfortunate victim of this whole affair,” he said.

On 20 April, Co Down beef farmer Ivan McKelvey appeared on the front page of the Irish Farmers Journal with some of his finished steers over 30 months that had been ruled out of any market, including intervention.

![]()

Click on the image to read the archive

The previous week’s edition, on 13 April, carried the headline “Factory cattle kill down by 80%” with the news that 50,000 finished Irish cattle were stacking up on farms as Irish beef got caught up in the UK BSE scare.

Public confidence in beef was swept away in a tidal wave of fear and mistrust

Little Irish beef was reported to be on European supermarket shelves and many third country markets, such as Libya and Iran, remained closed. “Public confidence in beef was swept away in a tidal wave of fear and mistrust,” wrote David Allen.

The 20 April edition reported that consumption of local beef in continental Europe was down 20% and consumption of Irish beef was down as far as 80% in some regions. The following week, further figures from Bord Bia suggested that beef consumption in Ireland dropped by 30% at the height of the scare. In Germany the drop in consumption was the sharpest national decline across Europe at 70%, but this had started to recover.

In the third week of the over 30-month cattle disposal scheme in Northern Ireland, James Campbell reported on 25 May that 6,046 cattle had so far been incinerated. Around 54,000 cattle had been registered as over 30 months in NI. Some 18,000 of these were cows, meaning that 30,000 clean cattle were still to be destroyed. There were also 6,000 bulls between 24 and 30 months, which at the time did not qualify for intervention or the disposal scheme.

By 8 June 1996, Matt Dempsey’s editorial noted that the fallout from the BSE crisis had spread from the initial shock to winter finishers throughout the whole industry to hit cull cow, store cattle and even calf prices.

No real strategy

That week, European Commission president Jacques Santer said in Dublin that there was no real strategy to address the BSE scare two months on. In protest at politicians’ handling of a debate on the issue, IFA president John Donnelly led a walk-out of 100 livestock farmers from Dáil Éireann.

On 29 June, the Irish Farmers Journal reported that an EU compensation fund had been agreed, with around £70m assigned to Ireland. This was to be mostly in the form of top-ups for suckler cow and beef premiums.

![]()

Click on the image to read the archive

However, editor Matt Dempsey pointed out that this covered only around half of the financial losses to suckler farmers, and less than half for winter finishers. By 20 July, the compensation was known to be worth £22.40 on the suckler cow and £19.08 on the beef premium.

The real effect of the crisis on family farms was seen by 31 August 1996. The front-page reported that beef incomes were estimated to have dropped by 40% as the IFA protested outside Leinster House to highlight the poor Government response to the crisis.

Stricter EU regulation targeted the use of bovine meat and bone meal as a source of protein in cattle feed. The practice was the main source of BSE contamination across Europe and was already banned in Ireland since 1990.

Second scare in 2000

Four years later, on 4 November 2000, “BSE – a dying kick” was a headline in the Irish Farmers Journal as news broke that French cattle from farms where BSE cases were detected had entered the food chain. This hit consumer confidence again, as did revelations that meat and bone meal was still being fed to pigs and poultry and being mixed in the same feed mill as ruminant feed.

In his editorial on 11 November 2000, Matt Dempsey sensed the danger: “It may be – and hopefully is – too alarmist to say that a 1996 type panic is in danger of re-erupting but the signs at this stage are not encouraging.”

![]()

Click on the image to read the archive

Irish farmers pressed then Minister for Agriculture Joe Walsh for BSE testing of all cattle over 30 months to guarantee BSE-free Irish beef and secure export markets, as reported in the Irish Farmers Journal on 25 November 2000.

“Controlled-risk” status

By that time, meat and bone meal was banned as a feed for livestock and the incidence of BSE in cattle was falling. It would be 2006, however, before over-30-month cattle could enter the food chain again and the UK export ban would be lifted in other EU countries.

Work to end bans in other countries continues to this day. Both the UK and Ireland still have a “controlled-risk” BSE status, a level below the ideal “negligible risk” status. To achieve this, a country or region must have 11 years pass since the birth of the last infected animal. Northern Ireland now qualifies to apply for negligible risk status, while the Republic of Ireland had achieved it for a short period in June 2015 before a new case was found in Co Louth in May 2015.

Phelim O’Neill contributed reporting for this story.

Read more

Special feature: BSE 20 years on

SHARING OPTIONS