It is now two years since the introduction of the Russian ban on food imports from the EU, USA, Canada, and other Western countries. What have Irish and Russian farmers learned from the experience – and is it likely sanctions will be lifted soon?

There are many jokes told about the difference between Russian and European farmers. But the most illuminating, and respectable, is this one: “Russian farmers are late starters, but fast learners!”

There are some prime examples and what has been described as “Russia’s crowning achievement” is that this year, for the first time in history, Russia will overtake America to become the biggest wheat exporter in the world. The country is forecast to ship 30m tonnes of wheat in 2016.

Russian livestock farmers are now also starting down the same road of phenomenal fast growth and extraordinary development. Russia’s capacity to be a large-scale, low-cost, high-profit, food producer and exporter, is practically unlimited.

Confirmation of this fact is not hard to find. For starters, within the last two years, from almost nowhere, Russia has become almost totally self-sufficient in pork and poultry meat.

Furthermore, some of Russia’s biggest pig and poultry producers are now already exporting their surplus stocks after supplying domestic markets.

Like Russian grain farmers, Russia’s pig and poultry farmers are currently also poised to become major global exporters. Russian exports of dairy products to EU and global markets may not be far away.

Confidence

The weaker currency and bumper grain crops has already injected a new-found confidence into all Russian farmers.

Consequently, many large-scale Russian grain farmers are now emboldened to hold on to some of their grain and add value to it. Specifically, Russian grain farmers are now starting to produce pigs and poultry on a large scale.

It helps a lot when a 115kg pig makes €160, the equivalent of €2 per kg carcase weight, which is 50c ahead of Irish prices. With production costs at rock bottom, many pig farmers are making a net profit of €60 to €70 per pig.

It of course helps when pork consumption per head in your home market of 145m upwardly mobile consumers, more than doubled in the last six years.

It helps even more when you’re producing 2m to 3m pigs per year.

At these profits, production efficiencies, and consumption rates, the return on capital invested in Russian pig farming is 25%.

Many new large-scale Russian dairy farms are also being planned and built. This is a logical development. Russian farm-gate milk prices are on average 37-38 cents per litre.

State grants and supports for farming remain high, and are likely to remain so. And this is farming on massive scale. Herds of 3,000 to 5,000 dairy cows are becoming the norm.

These are totally self-sufficient and integrated dairy operations. All forages and feeds are usually grown and produced on the integrated units that can range from 5,000 to 10,000 ha. With its scale, low cost of milk production and relatively high prices for milk at the farm gate, dairy farming in Russia is highly profitable.

A frightening prospect

All this is a seismic change in just two short years. In August 2014, the spectre of Russia’s traditional food queues again stalked the streets of Moscow. But within the last two years, Russian farmers have completely turned around their food supply chain and the momentum continues to gather pace.

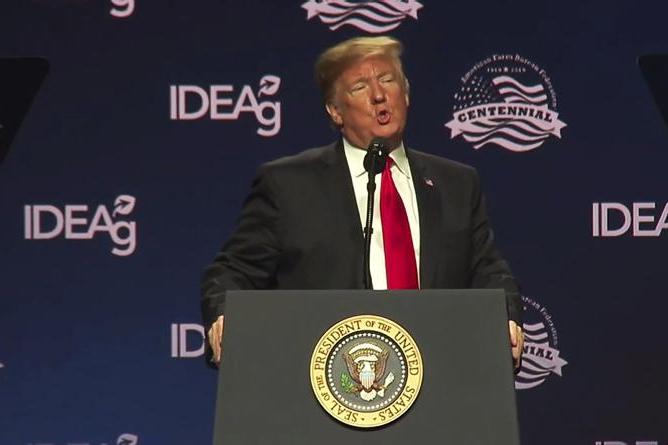

So it’s no surprise that Russian farmers are still toasting Barack Obama for helping them begin to farm to their full capacity. This is the first time in history that this has happened. Irish, European and American farmers better get accustomed to this new phenomenon.

Recently, president Putin extended Russia’s ban on food imports from the EU, USA, Canada, and others, to the end of 2017. Given all the major developments that are underway on Russian farms, that’s hardly a surprise.

*Brendan Dunleavy has over 20 years’ agribusiness project management experience in Russia and Ukraine

SHARING OPTIONS