This article taken from the KPMG-Irish Farmers Journal Agribusiness Report to be published this Thursday explores the resilience of the US dairy sector in the face of the current global crisis.

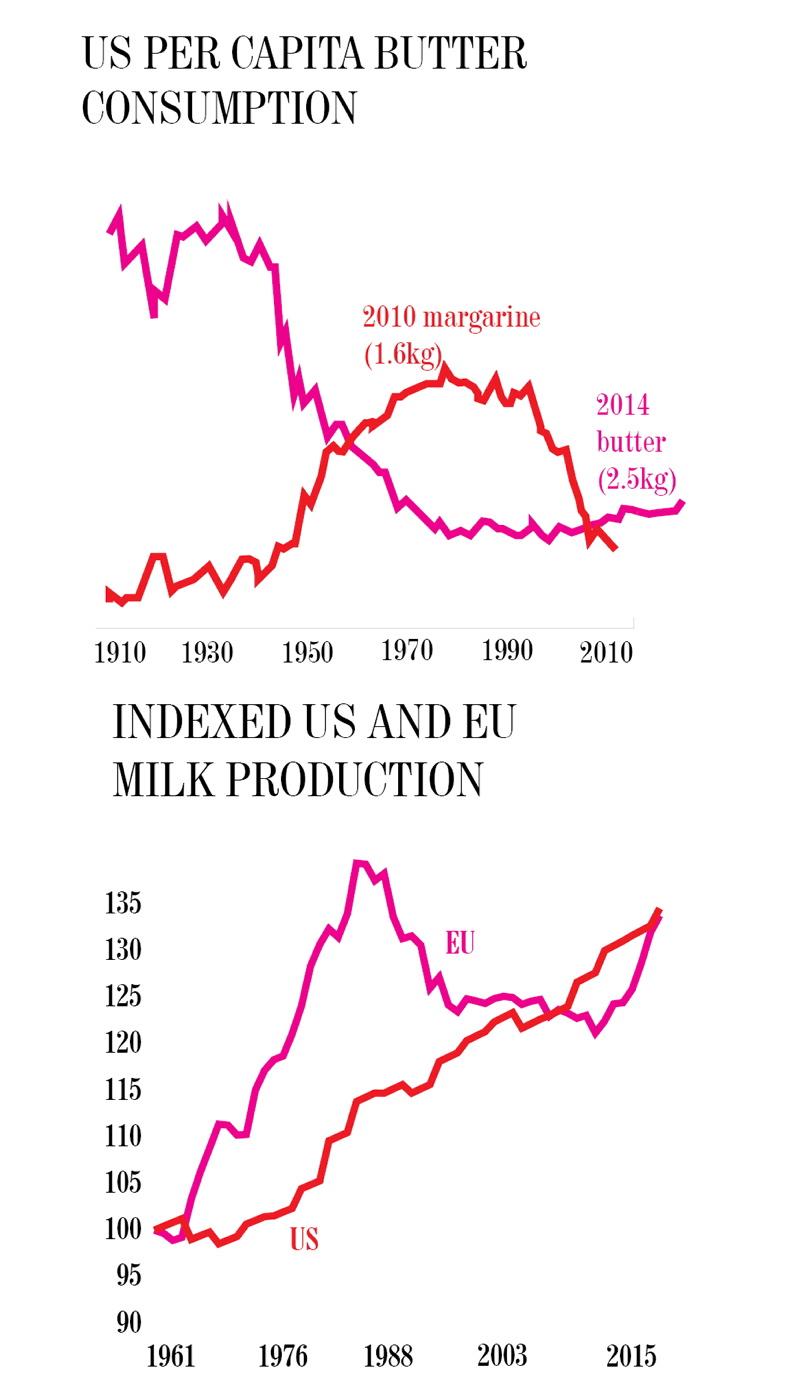

In the face of massive overproduction in the early 1980s, the European Commission implemented dairy production quotas in 1984 to curb output from EU dairy farmers. And while quotas were abolished in April last year and output is set to increase steadily in the years ahead, EU milk production is actually 5% behind where it was in 1984.

During that same 30-year period, US dairy farmers have always been free to produce as much as the market demanded. Since the early 1980s, US milk output has increased by more than 50% to almost 95m tonnes in 2015, with output forecast to increase a further 1.4%, or 1.3bn tonnes, this year.

What the US dairy industry has always been blessed with is a huge domestic market with a strong appetite for dairy products, particularly liquid milk, cheese, butter and ice cream.

What has been less clear is the US dairy sector’s commitment to the dairy export trade with less than 15% of the milk pool exported. Although US dairy exports have increased by 190% since 2003 to almost 1.7bn tonnes, the role of the US in the global export trade has largely been as a back filler in the market with New Zealand and EU exporters dominating.

Increasing

The value of US dairy exports last year was close to €4.6bn – a fourfold increase over the last decade but just €1bn greater in value than Irish dairy exports. Certainly, the bullish US dollar has held exports back over the last 18 months but it is still surprising to think that such a massive global producer does not have a greater presence in the global trade.

However, with strong domestic demand for butter and cheese in the US, dairy exports mainly comprise dried milk powders and whey products.

And with prices for these products on the floor in the world market for the last year, the focus of US processors has been squarely on the domestic market where returns are much stronger. Cheese prices in the US have remained indifferent over the last 12 months but the real story of the US dairy sector in the last year has been butter.

In May 2015, US butter prices were just over the $4,000/t mark, which was almost $750/t more than EU butter prices and $800/t more than New Zealand prices. Fast forward a year, and US butter prices have actually increased by more than 11% in the intervening period to over $4,500/t, while in New Zealand and the EU prices have declined by 21% and 15%, respectively.

Butter prices in the US are now almost $1,700/t higher than in the EU and nearly a massive $2,000/t higher than in New Zealand. But what is driving this surge in US butter prices? The primary reason is that US domestic consumption of butter has been growing strongly over the last five years. It is a product that has come back very much on trend with US consumers once again with per-capita demand back to levels not seen since after World War II.

Amazingly, another major stimulus for butter consumption in the US has been the new initiative by fast-food chain McDonald’s to offer an all-day breakfast option at its outlets.

Strong prices

With milk powder and whey prices so weak and cheese prices generally in line with the world market, Peter Vitaliano, chief economist with the National Milk Producers Federation in the US, estimates that the strong butter price contributed more than two thirds of farmers’ milk cheques in the US between November and December last year.

And while butter returns have historically contributed about 40% of the milk cheque in the US, Vitaliano is forecasting that the contribution from butter to US milk prices will remain above 50% for the rest of this year. As such, butter is now the key component in determining the milk price outlook in the US.

However, while the strong price of butter has propped up US milk prices over the last year in spite of the global downturn, it is one of many factors encouraging increased production from US farmers. Since the start of the year, US milk production has shown bullish increases with supply up by 1.8% in March alone to 8.4m tonnes.

The outlook is therefore darkening for US farmgate milk prices as a greater milk supply will lead to increased butter production and add to already high stocks of butter in the US, which will in turn drive prices downward.

Driver

So what is driving the increased production from US dairy farms? Data shows that the national dairy herd in the US has remained stable over the last 12 months, so the extra supply is coming from increased production per cow. No doubt the cheap price of grain is fuelling this. With cereal prices on the floor in the US, coupled with massive stocks from last year’s harvest, US dairy farmers have been able to increase feeding to cows at relatively little cost.

As such, US farmers are being urged to remain vigilant to what markets are telling them. Vitaliano believes that the broader international picture is that prices for milk powders and whey products will stay low for quite some time. In fact, Vitaliano estimates it will probably be at least another year before we see any uplift in powder prices because the oversupply situation, particularly from European producers, is “very very large” and showing no signs of turning around.

Protecting farmers' margins

On the back of the increasing supply seen in recent months, US milk prices are beginning to move into a lower cycle right now. This can be seen as farmers who are insured at the higher end of the scale under the USDA’s margin protection programme (MPP) are starting to receive insurance payments.

The MPP was enacted by the USDA in 2014 in response to the collapse in market prices in 2009 and again in 2012. The scheme allows farmers to insure or protect themselves with a margin on anything between 25% and 90% of their milk production. The level of margin farmers can insure themselves for is between $0.08/l at the lowest end of the scheme and $0.16/l at the highest end.

Payments are made to farmers by the USDA once their own production margin falls below the rate of insurance they have taken out. The minimum sign-up cost of the scheme is $100, which insures up to 90% of milk produced by the farmer for the basic margin of $0.08/l. If a farmer wishes to insure themselves with a higher margin, they pay a higher premium. The USDA estimates that had the MPP been in existence between 2009 and 2014, US dairy farmers would have paid in $500m in premiums and fees, while the USDA would have paid out $2.5bn in financial assistance or margin protection insurance to farmers.

The MPP is not the only volatility management mechanism available to US farmers. The Chicago Mercantile Exchange operates a futures milk market allowing producers to forward-sell portions of their milk output for a set price and thereby better manage farm cashflow.

Comment

Exporting about 85% of production every year, the Irish dairy sector is firmly playing in the global market with prices determined largely by the dynamics of global supply and demand. In the US, however, thanks to a large domestic market, it is less vulnerable to the vagaries of the global market.

In particular, the surge in butter consumption by US consumers has helped prop up the milk price for US farmers at a time when their counterparts in Europe and New Zealand are seeing the farmgate price for their milk hurtling to levels not seen since 2009.

And even with milk prices in the US starting to come under downward pressure in recent weeks, government support mechanisms are now kicking in to protect farmer margins.

Even though Ireland is one of the lowest -cost producers in the world, it doesn’t have the benefit of a large domestic market like the US. It also now operates in an open free market without direct government support.

Cheap grain, along with the margin protection program, ensures that the US dairy farmer will continue to make money and the milk supply tap will continue to flow.

This will be at the expense of global commodity dairy prices in two ways.

Firstly, prices will be weighed down directly through increased US exports.

And secondly, as the highest-cost producers normally set the floor for global prices, any government interference through margin supports indirectly reduces this floor.

To read the full Agribusiness report, click here.

SHARING OPTIONS