In the second part of our two-part series, we look at the fall and rise of Larry Goodman following his formative years. In August 1990, the first Gulf War cut off Goodman from customers in Iraq, some of whom owed him an estimated £60m in now uninsured debt.

Alternative contracts with Iran failed to materialise. The BSE scare was developing in the UK, closing down markets. Goodman had to sell stakes in recently bought UK subsidiaries to raise cash, incurring massive losses as stock markets were in freefall.

Despite all this, he told the Irish Farmers Journal that “the continuation of company policy to pay on the day can be taken as an indication of the continuing support of the group’s banks”.

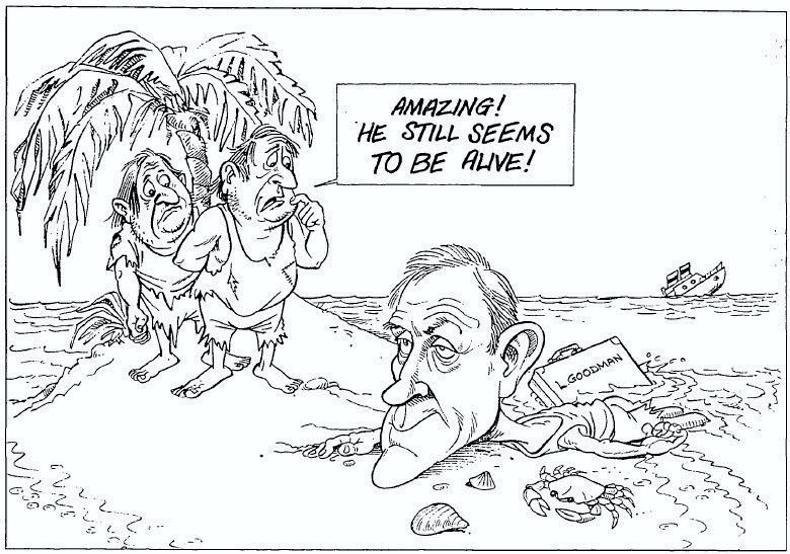

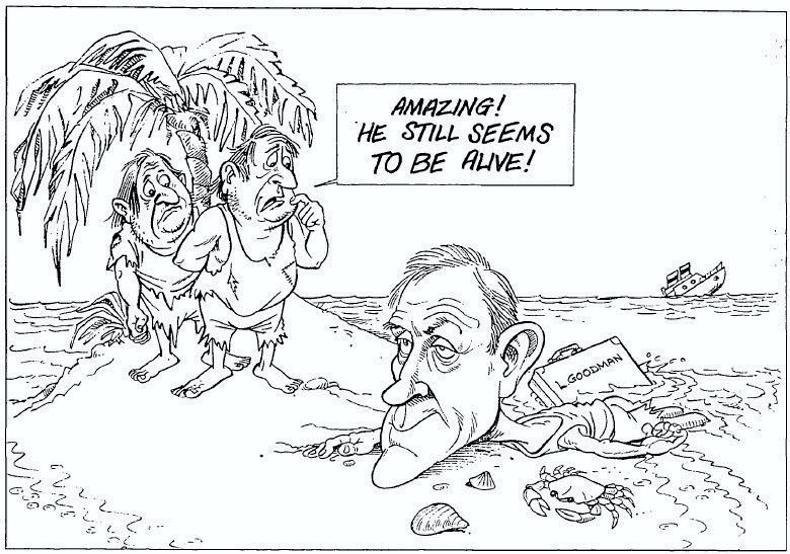

The Irish Farmers Journal’s editorial asked: “What are we to make of Larry Goodman?”

“The profits earned in his beef business down through the years have been extraordinary,” this newspaper wrote. Add his “fanatical devotion to efficiency” and “personal charisma”, and the banks “let him borrow over £400m without any security”. His failures on Iraq, his latest UK investments and BSE “contributed to his potential downfall”.

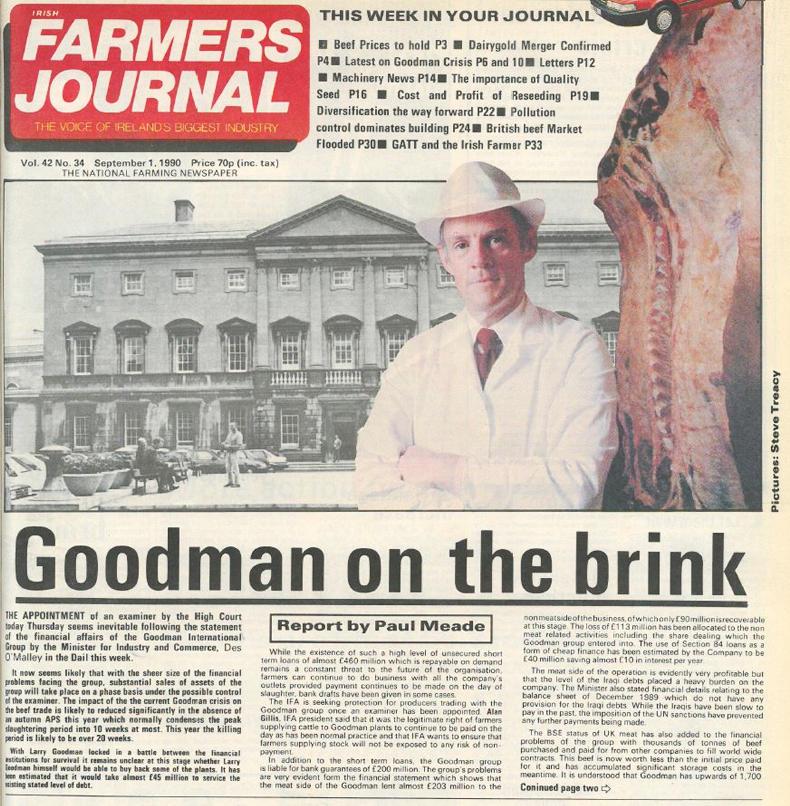

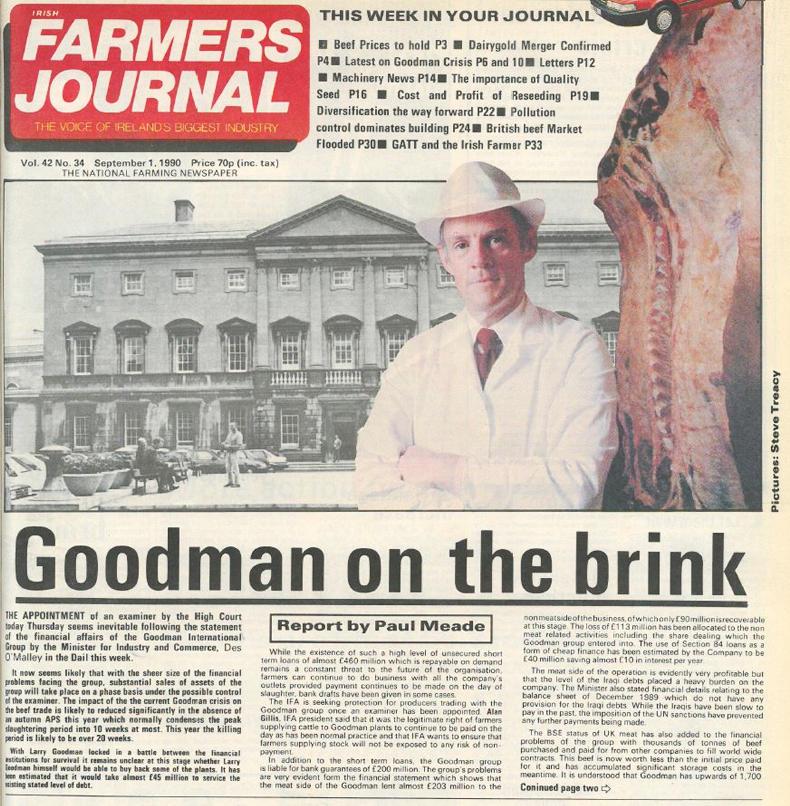

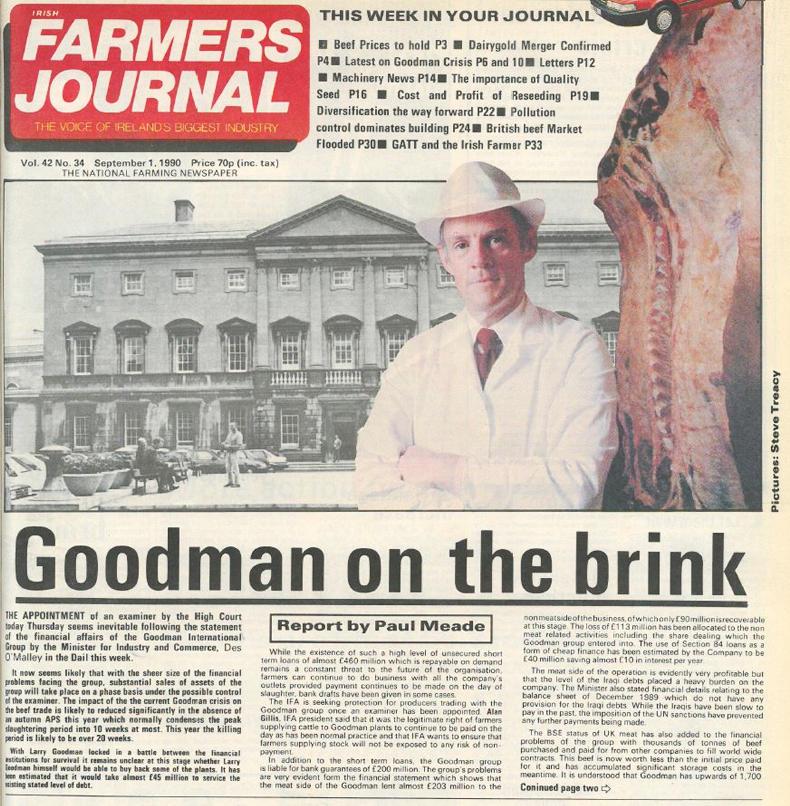

The following week, the High Court placed his companies into examinership – a new system rushed through the Dáil to avoid their liquidation. Our front page headline was “Goodman on the brink”.

Court proceedings revealed that Goodman controlled dozens of companies, including through an offshore firm in Liechstenstein.

The 33 Irish and foreign banks providing finance to the group’s parent company Goodman International could have called in loans worth £500m, but they knew they had little hope of recovering their funds. To use a more recent expression, they had “skin in the game”. Instead, they decided to keep the factories going to try to recoup their investment.

Their position received support from the IFA and the trade unions, who stressed the need to keep the plants open during the peak slaughtering period.

This newspaper wrote: “Irish farmers must not be asked to carry the cost of repaying the banks that broke all of their own rules when lending to the group.”

When the examiner and the banks agreed to take over Goodman’s profitable core meat business to recover up to £150m in restructured debt, the Irish Farmers Journal warned in an editorial that this would work out at £50/head to £60/head to be taken out of farmers’ pockets.

Cracks open

In May 1991, the programme World in Action produced by Granada TV picked up on the fraudulent activities reported in 1989 and 1990. The programme and a number of TDs made more revelations, accusing Goodman companies of abusing support schemes in multiple ways and the authorities under the Charles Haughey government of covering up the irregularities.

The Beef Tribunal was established immediately and chaired by Justice Liam Hamilton, the High Court presiding judge who had overseen the Goodman group’s examinership.

For the next two years, the tribunal heard allegations of fake stamps, illegal meat shipments across the border with Northern Ireland, under-the-counter payments, favouritism in access to Government grants, fictitious hauliers and fraudulent labelling.

This doesn’t mean all our managers are a shower of crooks

Lawyers for the Goodman group strenuously denied the accusations. Larry Goodman himself testified in March 1993.

While he admitted there had been breaches of regulations at some of his company’s plants, he described them as venial rather than mortal sins and said: “This doesn’t mean all our managers are a shower of crooks.” Throughout his four days in the witness box, Goodman said he had no firsthand knowledge of irregularities at his company’s plants.

However, he admitted to knowing that intervention beef had been relabelled for sale in Iraq. He said his relations with politicians amounted to lobbying rather than interference and blamed the negative publicity surrounding his business on “unethical competitors”.

When the Beef Tribunal’s report finally came out in August 1994, it found that Larry Goodman and the management and his companies must accept responsibility for failing to exercise effective control and ensuring compliance with regulations on public supports. The report also found that there was widespread tax evasion at AIBP plants.

It also concluded that the independence of the IDA was compromised by political pressure when allocating grants to the Goodman group.

However, Justice Hamilton stopped short of attributing the direct responsibility of any fraud to Larry Goodman.

During that time, the banks controlling Goodman’s meat factories were making progress in recovering their funds from asset sales and the company’s profits.

In 1995, a consortium of investors including a 36% stake from Larry Goodman bought the business from the banks for £40m and renamed it Irish Food Processors, on the basis that it continued to repay outstanding debts. He and his family quickly ramped up to 45% and, by the autumn of 1999, had regained full control of his beef empire.

Recent times

By 2004, the company now known as ABP had topped the €1bn sales mark and Goodman took it into private ownership.

It then stopped publishing accounts and its owner himself became more secretive.

He has not accepted requests for interviews with the Irish Farmers Journal in many years. ABP was in the spotlight again when the 2013 EU-wide horsemeat scandal erupted after tests on burgers supplied by the company – although the company was later found to have been abused by its own suppliers.

The group’s recent expansion has focused acquisitions in Poland and the Slaney joint venture announced last year.

Goodman’s personal forays into property and private hospitals have also attracted some attention – including through his bitter court battle with co-investors in the Blackrock Clinic.

A barrister recently told the High Court that the time spent on the case was “substantial” and “unusual”.

According to the 2017 Sunday Times rich list, Larry Goodman and his family have the 21st largest fortune in Ireland, at an estimated €650m.

Read more

Goodman at 80: part 1 – the rise of an empire

In the second part of our two-part series, we look at the fall and rise of Larry Goodman following his formative years. In August 1990, the first Gulf War cut off Goodman from customers in Iraq, some of whom owed him an estimated £60m in now uninsured debt.

Alternative contracts with Iran failed to materialise. The BSE scare was developing in the UK, closing down markets. Goodman had to sell stakes in recently bought UK subsidiaries to raise cash, incurring massive losses as stock markets were in freefall.

Despite all this, he told the Irish Farmers Journal that “the continuation of company policy to pay on the day can be taken as an indication of the continuing support of the group’s banks”.

The Irish Farmers Journal’s editorial asked: “What are we to make of Larry Goodman?”

“The profits earned in his beef business down through the years have been extraordinary,” this newspaper wrote. Add his “fanatical devotion to efficiency” and “personal charisma”, and the banks “let him borrow over £400m without any security”. His failures on Iraq, his latest UK investments and BSE “contributed to his potential downfall”.

The following week, the High Court placed his companies into examinership – a new system rushed through the Dáil to avoid their liquidation. Our front page headline was “Goodman on the brink”.

Court proceedings revealed that Goodman controlled dozens of companies, including through an offshore firm in Liechstenstein.

The 33 Irish and foreign banks providing finance to the group’s parent company Goodman International could have called in loans worth £500m, but they knew they had little hope of recovering their funds. To use a more recent expression, they had “skin in the game”. Instead, they decided to keep the factories going to try to recoup their investment.

Their position received support from the IFA and the trade unions, who stressed the need to keep the plants open during the peak slaughtering period.

This newspaper wrote: “Irish farmers must not be asked to carry the cost of repaying the banks that broke all of their own rules when lending to the group.”

When the examiner and the banks agreed to take over Goodman’s profitable core meat business to recover up to £150m in restructured debt, the Irish Farmers Journal warned in an editorial that this would work out at £50/head to £60/head to be taken out of farmers’ pockets.

Cracks open

In May 1991, the programme World in Action produced by Granada TV picked up on the fraudulent activities reported in 1989 and 1990. The programme and a number of TDs made more revelations, accusing Goodman companies of abusing support schemes in multiple ways and the authorities under the Charles Haughey government of covering up the irregularities.

The Beef Tribunal was established immediately and chaired by Justice Liam Hamilton, the High Court presiding judge who had overseen the Goodman group’s examinership.

For the next two years, the tribunal heard allegations of fake stamps, illegal meat shipments across the border with Northern Ireland, under-the-counter payments, favouritism in access to Government grants, fictitious hauliers and fraudulent labelling.

This doesn’t mean all our managers are a shower of crooks

Lawyers for the Goodman group strenuously denied the accusations. Larry Goodman himself testified in March 1993.

While he admitted there had been breaches of regulations at some of his company’s plants, he described them as venial rather than mortal sins and said: “This doesn’t mean all our managers are a shower of crooks.” Throughout his four days in the witness box, Goodman said he had no firsthand knowledge of irregularities at his company’s plants.

However, he admitted to knowing that intervention beef had been relabelled for sale in Iraq. He said his relations with politicians amounted to lobbying rather than interference and blamed the negative publicity surrounding his business on “unethical competitors”.

When the Beef Tribunal’s report finally came out in August 1994, it found that Larry Goodman and the management and his companies must accept responsibility for failing to exercise effective control and ensuring compliance with regulations on public supports. The report also found that there was widespread tax evasion at AIBP plants.

It also concluded that the independence of the IDA was compromised by political pressure when allocating grants to the Goodman group.

However, Justice Hamilton stopped short of attributing the direct responsibility of any fraud to Larry Goodman.

During that time, the banks controlling Goodman’s meat factories were making progress in recovering their funds from asset sales and the company’s profits.

In 1995, a consortium of investors including a 36% stake from Larry Goodman bought the business from the banks for £40m and renamed it Irish Food Processors, on the basis that it continued to repay outstanding debts. He and his family quickly ramped up to 45% and, by the autumn of 1999, had regained full control of his beef empire.

Recent times

By 2004, the company now known as ABP had topped the €1bn sales mark and Goodman took it into private ownership.

It then stopped publishing accounts and its owner himself became more secretive.

He has not accepted requests for interviews with the Irish Farmers Journal in many years. ABP was in the spotlight again when the 2013 EU-wide horsemeat scandal erupted after tests on burgers supplied by the company – although the company was later found to have been abused by its own suppliers.

The group’s recent expansion has focused acquisitions in Poland and the Slaney joint venture announced last year.

Goodman’s personal forays into property and private hospitals have also attracted some attention – including through his bitter court battle with co-investors in the Blackrock Clinic.

A barrister recently told the High Court that the time spent on the case was “substantial” and “unusual”.

According to the 2017 Sunday Times rich list, Larry Goodman and his family have the 21st largest fortune in Ireland, at an estimated €650m.

Read more

Goodman at 80: part 1 – the rise of an empire

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: