Fracking of shale gas, be it in America or Ireland, is a divisive issue. Depending on what side of the fence you sit on, fracking is either a genuine option to safeguard the country’s long-term energy needs or a potentially dangerous practice which could irreparably damage the environment. The proponents of and opponents to fracking are not for changing.

While the potential effects of fracking on the environment have yet to be comprehensively proven, the economic benefits to the areas which have adopted fracking are clear.

By 2018 the US will be a larger gas producer than Russia and by 2020 it will be the largest producer in the world.

In the state of Ohio, commercial and large-scale fracking has been in operation for the past two years. Opposition to the practice remains vociferous despite the obvious flourishing of the economy in areas where energy companies have set up operations in the state.

Chesapeake, Exxon, Devon Energy and Anadarko are just a handful of the multinational energy companies that have established operations in the largely rural state.

Two weeks ago, the Irish Farmers Journal visited farmers in Carroll County, three hours east of Ohioan state capital Columbus to learn more about fracking in the area and the impact it has had on the communities.

Large-scale and commercial fracking for shale gas has been in operation here since late 2011. In that time, Carroll has become the site of a veritable modern-day gold rush. More than 300 wells have been drilled with an expectation that the figure will rise to nearly 900 within three years.

Chesapeake has operations on about 1.8m acres in Ohio, Devon has 235,000 acres while Anadarko has fracking sites on 390,000 acres of land.

Dr Keith Burgett is a local vet and Angus breeder from Antigua Road, Carrollton. As well as those occupations, he is also described as being an “energy entrepreneur” due to the fracking operation under way on his farm. While Burgett has lost just a 6 acre plot to the fracking pad on his land, pipes run under 600 acres of his farm.

The economic benefits are clear for Dr Burgett.

“I’ve secured the future of the farm for my children and their children. It has brought great wealth and prosperity to the area and has meant that there is a clear future for farming in the area,” he said.

As he owns the mineral rights to his land, Burgett receives royalties from Chesapeake for the shale gas. Land now being sold in Ohio is going in two lots – the resources above the ground (grass, corn, etc.) and the mineral rights in the ground.

Prior to any fracking taking place, a farmer is offered an option agreement by an energy company worth in the region of $50 (€38) per acre for the company to have first refusal on the site in the event that it ends up fracking. Once it has been determined that there is shale gas in the ground, the farmer negotiates a new deal where the company pays a royalty to the farmer on the money it generates, typically 10-20%.

For Dr Burgett, this equates to $600 (€463) per acre, per month. In total, this means that Dr Burgett can make as much as $4.3m (€3.3m), although the tax take for the government is somewhere in the region of 40-50%.

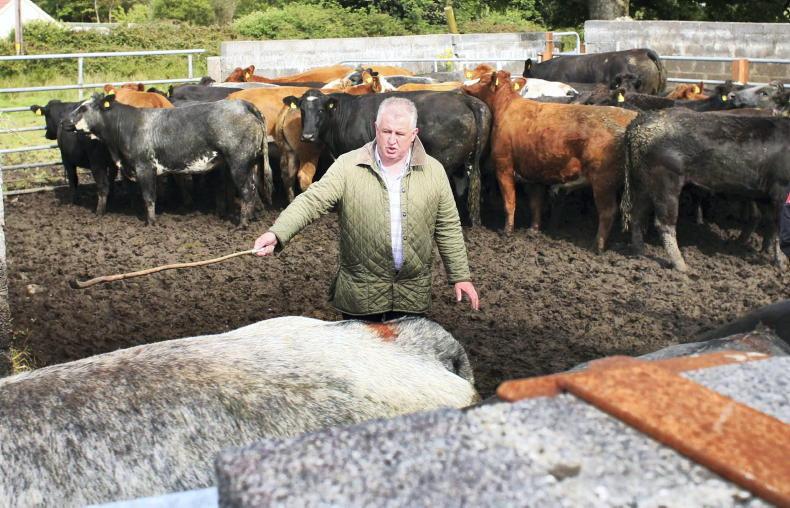

Vernon Cummings is a suckler farmer also from Carroll County who has one well on his land for the past two years. Cummings explains how fracking has impacted on his farm.

“I was making no money at beef,” Cummings said. “I’ve changed my system to a cow-calf one (suckler) because it’s an easier lifestyle. I bought a new tractor and I renovated my barn. I wouldn’t have been able to do that without fracking. Fracking has a lot of detractors but it’s on my farm and I have first-hand experience and knowledge of it. Not one bad thing has happened as a result of fracking in our area.”

As you drive through Carroll County, the shale gas industry boom is clear to see. The county’s capital town, Carrollton, has never been more prosperous and is at the epicentre of fracking in the state.

With a population of just over 3,000 and being heavily influenced by the rural communities in the surrounds, Carrollton has always been an agriculture-dominated town.

Since shale gas exploration and extraction began, there has been rapid economic growth in the area. Two new hotels have been built in two years, with planning permission being sought for a further one. Diners are full every day, jobs have been created and the town is booming. This has been replicated across the state.

In the time that fracking has been in operation in Ohio, unemployment rates have fallen consistently. From 9% at the end of 2011 to stand 4.8% currently. A study by the University of Ohio released earlier this year showed that job growth and improved economic conditions were directly linked to the increased fracking activity.

The Ohioan department of enterprise has said close to 10,000 direct jobs have been created in the state from fracking, with several thousand more indirect jobs created. Most of these indirect jobs have come in the services sector.

Opposition to fracking in Carroll County has been, and continues to be vocal.

While economic benefits might be good at present for local farmers, the long-term economics, as well as the long-term reserves, are still questionable.

In America, the shale gas evolution has revolutionised the energy market. It has lowered energy costs for most consumers but walks a narrow tightrope of efficiency with oil prices. Once oil prices stay above $90 per barrel, shale gas is financially viable. If oil prices drop below that on a consistent level, it does not make financial sense to keep it operating on such an intensive exploration.

Gas companies say that there is enough shale gas under Ohio to last more than 30 years, but it is a difficult resource to quantify. The less optimistic observers say that wells could be dry within 15 years, leaving the scars of fracking wells on the landscape.

The environmental and health concerns remain and fuel most of the opposition. Scientists and geologists from Youngstown University, Ohio, have linked fracking to earthquakes which have been recorded in the state. In March, a magnitude 4.0 earthquake was measured on the Ohio-Pennsylvania border. There have also been smaller but regular quakes detected near fault lines where fracking wells are located.

Serious question marks remain over the danger of fracking to the water bed as well as pollutants from the waste water generated from fracking. Many say that the dangers from fracking are too great to the environment. Although with Chesapeake reporting profits of $1.5bn last year and the local economies thriving, the objections by the opposition are not gaining much traction.

What is fracking

Hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, is a process where narrow holes are drilled deep into the ground (vertically and then horizontally) before a pipe is passed into the hole. The pipe is encased in concrete. High-pressure water, sand and chemicals are pumped through the pipe to cause mini-fractures in the earth to release shale gas. The gas is then passed back on to the earth’s surface to be collected in tanks. The gas collected is brought to refineries to be used as natural gas or propane by energy companies.

Fracking in Ireland – where are we?

In 2011, fracking became a hot topic in Ireland. Three companies – Enegi Oil, Tamboran Resources and the Lough Allen Natural Gas Company (LANGS) – all announced intentions to seek licences to frack in different areas.

LANGS want to explore the Lough Allen basin, Enegi is targeting a basin in Clare while Tamboran has previously said that as much as 2.2bn cubic metres of shale gas could be under the ground along the Fermanagh/Leitrim border.

Tamboran started exploratory drilling at a site in Belcoo, Co Fermanagh, in August only to have permission restricted afterwards by the Northern Ireland Assembly. Despite this, it is expected that Tamboran will be able to recommence testing in the near future.

For the South, the position is unclear. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was tasked with carrying out research regarding the potential impacts fracking has on the environment.

The Department of Energy and Natural Resources expects the report to be completed by 2016 at the earliest.

However, the Irish Government is understood to be adopting a “wait and see” approach to fracking in the North. Should Tamorban be awarded a licence to frack and should there be the economic and social benefits for the area, then the Irish Government would be more inclined to push for fracking to take place here.

Despite the fact that any type of commercial fracking taking place in the Republic of Ireland is at least two and half years away, the opposition remains strong.

Various groups in the northwest have been extremely vocal in their opposition to any fracking plans and there has been little to no support to the plans. Although global pressure on gas supplies remains.

SHARING OPTIONS