With cattle coming inside for finishing and winter slowly creeping in, it’s important to be aware of the potential pitfalls as we switch away from a grass diet. Nutritional disorders can be disastrous, hitting production hard. What’s even worse is that ailments like acidosis can occur in sub-clinical forms, ie the animal shows no obvious symptoms but growth rate flatlines. In other words, we can spend weeks and months bucketing barley into cattle that are converting next-to-nothing.

The main nutritional disorders to look out for this back-end will be acidosis, and the ailments that it leads to, in finishing cattle and listeriosis in animals eating silage.

Acidosis

When we feed cattle, there is a third party involved – the rumen. In simple terms, bugs in the rumen break down feeds into acid compounds, which the animal can use as a source of energy. There are billions of these bugs in the rumen and prevailing bug-type will be based entirely on the animal’s diet. For example, fibre-digesting bugs will predominate in a forage-based scenario and starch-digesters in cattle on intensive finishing diets.

These bugs do not like change. The growth check that comes in the first few days of a switch in diet type is due to an adjusting rumen bug population. Where this occurs gradually in cattle moving to a high-concentrate diet, there should be no issues. The rumen population needs enough time to evolve and adapt to cope with the surge in acid production that comes with a high-concentrate diet.

If the change to a starchy, high-concentrate diet is a spontaneous one, there will suddenly be more acid in the rumen than the existing bug population can cope with. If the problem is pronounced enough, the acid will damage the rumen wall, affecting the animal’s ability to absorb nutrients. The capacity of the rumen wall to absorb nutrients can be affected for up to six months following a bout of acidosis.

Acidosis can be acute, where the rumen pH is below 5.2 for an extended period, or sub-acute (SARA), where pH drops to 5.5 or less for an extended period.

Acute acidosis has pronounced symptoms and typically occurs during the adaption to high-concentrate diets. It is the type that will leave lasting effects on our animal, if they survive. Symptoms of acute acidosis include:

Violent diarrhoea. Abdominal kicking.Rapid breathing.Staggering.Death.Sub-acute acidosis is more difficult to detect and although the effects on the individual animal won’t be as severe as acute acidosis, bouts of SARA typically affect multiple animals in a group and, if undetected, can have huge financial implications as production nose-dives. Symptoms include:

Less than 60% of resting animals in a group ruminating at a given time.Loose, bubbly dung.Greater than 10% incidence of laminitis.Poor intakes and weight gain.Lethargy.Increased respiratory rate.Knock-on effects

In addition, acidosis predisposes animals to other ailments. A build-up of acids in the rumen leads to the formation of inflammatory agents which can travel to the animal’s feet via the bloodstream and cause lameness. A damaged rumen wall can also facilitate the absorption of unwanted bacteria into the bloodstream. These bacteria accumulate in the liver and can cause liver abscesses. Acidosis can also lead to bloating as the viscosity of the fluid in the rumen changes and traps gas, which would otherwise be belched out, as foam. As the animal bloats up, physical pressure is put on the lungs which can lead to suffocation.

Prevention of acidosis

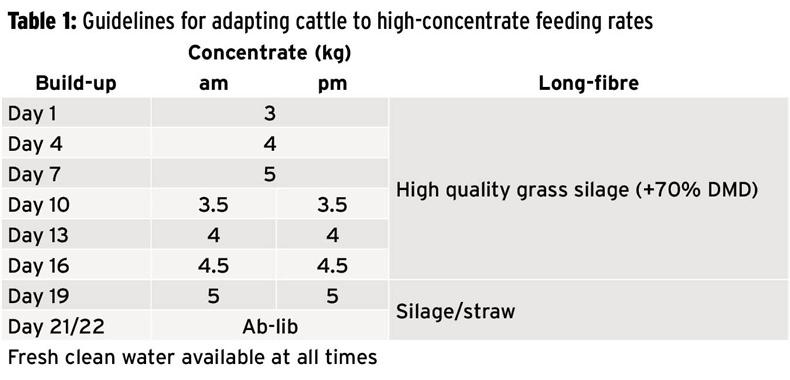

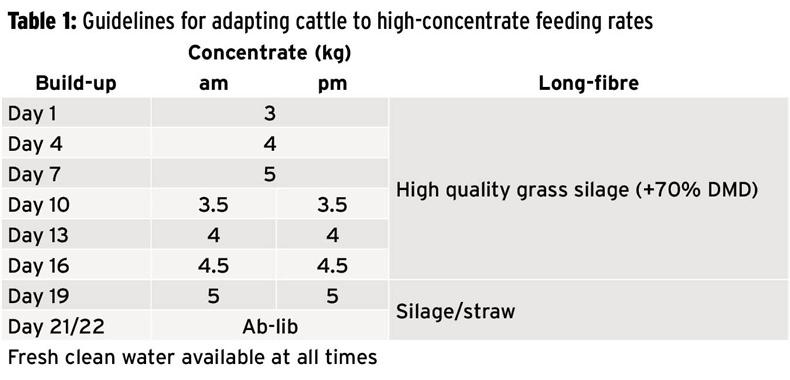

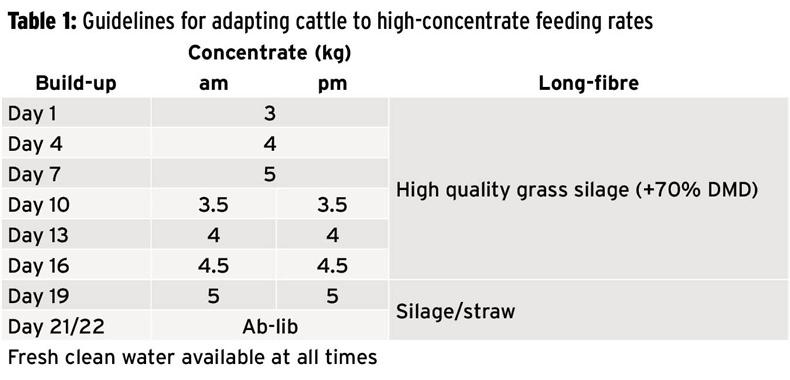

Prevention is the name of the game with acidosis. Gradual adaption to a high-concentrate diet affords the rumen population time to acclimatise. When building up to any type of finishing diet (Table 1), offer no more than 3kg of meals per head initially.

Then, increase meal allowance by 1kg every three days. Delay an increase if animals are slow to consume the meals or if there is any evidence of the above SARA symptoms. Above 5kg of feeding daily, split feeds in two and continue to increase total daily feed allowance by 1kg every three days. Once animals are consuming 10kg daily, concentrates can be offered ad-lib and feed should never be allowed to run out.

Fibre and fluid

Cattle should have access to long fibre (straw/silage) at all times. Hay can be offered too, but in my experience cattle sometimes eat too much hay if given the opportunity and concentrate intake is affected – reducing performance.

Long fibre stimulates rumen contractions, which help to prevent acid from accumulating in the stomach. It also slows down the rate of rumen digestion and promotes both cud chewing and salivation – all of which help to prevent acidotic conditions. Cattle will self-regulate their long fibre intake, but cannot if it runs out. Finishing cattle on ad lib will eat 5-6kg of fresh grass silage per head daily along with their meals. If offering straw, allow 2kg per head. At very high levels of concentrate feeding, the animal will be getting very little energy from the fibre it eats as starch-digesting bugs will have taken over in the rumen. Hence there is little benefit to feeding high-quality grass silage at these concentrate feeding levels – poor silage (provided they eat it) or straw will do. Water is crucial too and water issues can be a big contributor to below-par performance in finishing situations. In ad-lib feeding scenarios, small troughs with poor water flow rate can limit performance.

The animal will get lazy and won’t wait for the trough to fill. They’ll lie down having taken on insufficient fluid and their subsequent intakes that day will be lower as a result. If at all possible, cattle on ad-lib need to be provided with access to multiple water points with good flow rates and/or large-volume troughs.

Feed additives

Most farmers purchasing compound feed mixes are unaware that what they’re feeding their cattle likely contains additives to prevent acidosis already. On feed labels, ingredients such as sodium bicarbonate and calcium carbonate appearing at the end of the list are buffers. These compounds act in a fire-fighting mechanism by neutralising acid conditions. The anti-indigestion tablets that you or I take after a takeaway contain the same ingredients. Yeasts and probiotics are also common in compound feeds and work by optimising rumen bug efficiency. On feed labels, these appear as saccharomyces cervisae and aspergillus oryzae, among others.

Listeriosis

Listeriosis is a brain infection in cattle caused by the bacteria listeria. These bacteria can accumulate in mouldy silage and in silages contaminated with soil at harvest. Although more common in younger cattle, listeriosis can affect pregnant cows, causing abortions. The bacteria can also cause nasty eye problems in cows and sheep, beginning as faint white spots in the centre of the eye, but quickly causing clouding of the whole eye and blindness if not picked up.

Cattle with listeriosis will walk in circles and sometimes tilt their heads sideways. They can also exhibit stroke-like conditions – a drooping of the ear, eye and mouth on one side of the face. Often where cattle show these kinds of extreme symptoms, the prospects for recovery are weak. Their swallowing ability will have been affected and they can fail very quickly.

Prevention

Reduce the risks of listeriosis by continually removing mouldy silage from the feed face, particularly from younger animals. Dry cows will usually draw the short straw on beef farms during the winter, getting the very worst silage that’s on offer. I have experienced listeria-induced abortions brought about by bad bales. It was grim and worse, entirely avoidable. If feeding bales that are known to be mouldy with a loader, swallow your pride, hop down from the cab, grab a fork and pick out the mould. You might work up a sweat, but it’ll be nothing like the potential sweat you would work up seeing four or five aborted calves on the slats on a morning in January.

Read more

Focus: Winter animal health

With cattle coming inside for finishing and winter slowly creeping in, it’s important to be aware of the potential pitfalls as we switch away from a grass diet. Nutritional disorders can be disastrous, hitting production hard. What’s even worse is that ailments like acidosis can occur in sub-clinical forms, ie the animal shows no obvious symptoms but growth rate flatlines. In other words, we can spend weeks and months bucketing barley into cattle that are converting next-to-nothing.

The main nutritional disorders to look out for this back-end will be acidosis, and the ailments that it leads to, in finishing cattle and listeriosis in animals eating silage.

Acidosis

When we feed cattle, there is a third party involved – the rumen. In simple terms, bugs in the rumen break down feeds into acid compounds, which the animal can use as a source of energy. There are billions of these bugs in the rumen and prevailing bug-type will be based entirely on the animal’s diet. For example, fibre-digesting bugs will predominate in a forage-based scenario and starch-digesters in cattle on intensive finishing diets.

These bugs do not like change. The growth check that comes in the first few days of a switch in diet type is due to an adjusting rumen bug population. Where this occurs gradually in cattle moving to a high-concentrate diet, there should be no issues. The rumen population needs enough time to evolve and adapt to cope with the surge in acid production that comes with a high-concentrate diet.

If the change to a starchy, high-concentrate diet is a spontaneous one, there will suddenly be more acid in the rumen than the existing bug population can cope with. If the problem is pronounced enough, the acid will damage the rumen wall, affecting the animal’s ability to absorb nutrients. The capacity of the rumen wall to absorb nutrients can be affected for up to six months following a bout of acidosis.

Acidosis can be acute, where the rumen pH is below 5.2 for an extended period, or sub-acute (SARA), where pH drops to 5.5 or less for an extended period.

Acute acidosis has pronounced symptoms and typically occurs during the adaption to high-concentrate diets. It is the type that will leave lasting effects on our animal, if they survive. Symptoms of acute acidosis include:

Violent diarrhoea. Abdominal kicking.Rapid breathing.Staggering.Death.Sub-acute acidosis is more difficult to detect and although the effects on the individual animal won’t be as severe as acute acidosis, bouts of SARA typically affect multiple animals in a group and, if undetected, can have huge financial implications as production nose-dives. Symptoms include:

Less than 60% of resting animals in a group ruminating at a given time.Loose, bubbly dung.Greater than 10% incidence of laminitis.Poor intakes and weight gain.Lethargy.Increased respiratory rate.Knock-on effects

In addition, acidosis predisposes animals to other ailments. A build-up of acids in the rumen leads to the formation of inflammatory agents which can travel to the animal’s feet via the bloodstream and cause lameness. A damaged rumen wall can also facilitate the absorption of unwanted bacteria into the bloodstream. These bacteria accumulate in the liver and can cause liver abscesses. Acidosis can also lead to bloating as the viscosity of the fluid in the rumen changes and traps gas, which would otherwise be belched out, as foam. As the animal bloats up, physical pressure is put on the lungs which can lead to suffocation.

Prevention of acidosis

Prevention is the name of the game with acidosis. Gradual adaption to a high-concentrate diet affords the rumen population time to acclimatise. When building up to any type of finishing diet (Table 1), offer no more than 3kg of meals per head initially.

Then, increase meal allowance by 1kg every three days. Delay an increase if animals are slow to consume the meals or if there is any evidence of the above SARA symptoms. Above 5kg of feeding daily, split feeds in two and continue to increase total daily feed allowance by 1kg every three days. Once animals are consuming 10kg daily, concentrates can be offered ad-lib and feed should never be allowed to run out.

Fibre and fluid

Cattle should have access to long fibre (straw/silage) at all times. Hay can be offered too, but in my experience cattle sometimes eat too much hay if given the opportunity and concentrate intake is affected – reducing performance.

Long fibre stimulates rumen contractions, which help to prevent acid from accumulating in the stomach. It also slows down the rate of rumen digestion and promotes both cud chewing and salivation – all of which help to prevent acidotic conditions. Cattle will self-regulate their long fibre intake, but cannot if it runs out. Finishing cattle on ad lib will eat 5-6kg of fresh grass silage per head daily along with their meals. If offering straw, allow 2kg per head. At very high levels of concentrate feeding, the animal will be getting very little energy from the fibre it eats as starch-digesting bugs will have taken over in the rumen. Hence there is little benefit to feeding high-quality grass silage at these concentrate feeding levels – poor silage (provided they eat it) or straw will do. Water is crucial too and water issues can be a big contributor to below-par performance in finishing situations. In ad-lib feeding scenarios, small troughs with poor water flow rate can limit performance.

The animal will get lazy and won’t wait for the trough to fill. They’ll lie down having taken on insufficient fluid and their subsequent intakes that day will be lower as a result. If at all possible, cattle on ad-lib need to be provided with access to multiple water points with good flow rates and/or large-volume troughs.

Feed additives

Most farmers purchasing compound feed mixes are unaware that what they’re feeding their cattle likely contains additives to prevent acidosis already. On feed labels, ingredients such as sodium bicarbonate and calcium carbonate appearing at the end of the list are buffers. These compounds act in a fire-fighting mechanism by neutralising acid conditions. The anti-indigestion tablets that you or I take after a takeaway contain the same ingredients. Yeasts and probiotics are also common in compound feeds and work by optimising rumen bug efficiency. On feed labels, these appear as saccharomyces cervisae and aspergillus oryzae, among others.

Listeriosis

Listeriosis is a brain infection in cattle caused by the bacteria listeria. These bacteria can accumulate in mouldy silage and in silages contaminated with soil at harvest. Although more common in younger cattle, listeriosis can affect pregnant cows, causing abortions. The bacteria can also cause nasty eye problems in cows and sheep, beginning as faint white spots in the centre of the eye, but quickly causing clouding of the whole eye and blindness if not picked up.

Cattle with listeriosis will walk in circles and sometimes tilt their heads sideways. They can also exhibit stroke-like conditions – a drooping of the ear, eye and mouth on one side of the face. Often where cattle show these kinds of extreme symptoms, the prospects for recovery are weak. Their swallowing ability will have been affected and they can fail very quickly.

Prevention

Reduce the risks of listeriosis by continually removing mouldy silage from the feed face, particularly from younger animals. Dry cows will usually draw the short straw on beef farms during the winter, getting the very worst silage that’s on offer. I have experienced listeria-induced abortions brought about by bad bales. It was grim and worse, entirely avoidable. If feeding bales that are known to be mouldy with a loader, swallow your pride, hop down from the cab, grab a fork and pick out the mould. You might work up a sweat, but it’ll be nothing like the potential sweat you would work up seeing four or five aborted calves on the slats on a morning in January.

Read more

Focus: Winter animal health

SHARING OPTIONS