The increasing prospect of a hard Brexit has led some commentators in search of a silver lining to encourage Irish agri-food exporters to work towards replacing British exports to the continent.

British Prime Minister Theresa May said last week that the UK would exit the single market. While she hopes that a free trade agreement between the UK and the EU will replace current arrangements, this is widely seen as unrealistic in the short term.

It is therefore likely that some trade barriers will appear between the UK and the EU after it leaves the bloc. So could this be a chance for Irish food to replace British exports, both at home and on the continent? To get a sense of the potential opportunities, let’s take a look at UK customs statistics.

While the UK’s largest food export category to the continent is grain, this is a global market and there is little prospect for Ireland to grow its tillage sector and compete with the breadbaskets of the world there.

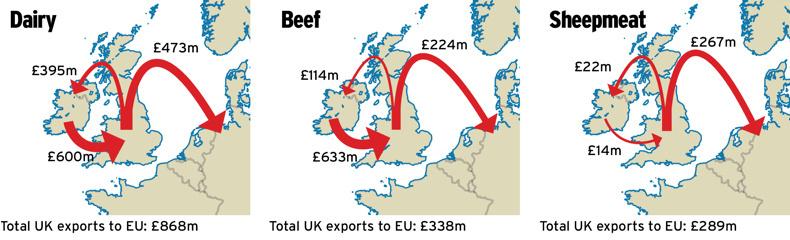

Next in line is dairy: the UK exported £868m (€1bn at today’s exchange rate) worth of dairy products to the EU in 2015 – nearly half of which went to Ireland. Meanwhile, Ireland exported £600m (€695m) to the UK. While a lot of this has to do with cross-border milk processing, there appears to be scope for Irish dairy processors to expand on the continent if British ones were to reduce their presence there – but this would mean a costly rethink of the products and marketing currently used in the UK to meet continental consumer preferences.

The beef sector, too, presents large volumes of three-way trade. However, British exports to the entire EU represent only about half of the Irish beef going into the UK. Here again, some degree of a carrousel effect is at play, with beef travelling back and forth across the Irish sea for processing. But in a total trade war scenario, the Irish beef industry is so dependent on the UK that losing its market there while replacing all British exports both at home and on the continent would still leave it out of pocket to the tune of £295m (€342m).

A rare opportunity seems to exist for sheepmeat, where the UK exports large volumes of high-value products to the continent, worth £267m (€309m). If this was to cease, Irish exporters could capture some markets there – potentially more than they would lose in the UK (£14m or €16m).

However, a side effect of this would be the fate of New Zealand lamb imports into the EU, which amounted to £436m last year. The largest importer is the UK, which took £244m worth of NZ lamb last year. Would the EU revise down New Zealand’s lamb quota as a result of Brexit, or risk flooding the continent with kiwi lamb?

The horticulture sector, too, could potentially benefit, with British fruit and veg exports to the continent much larger than Irish exports to the UK. The fate of mushroom producers decimated by the recent fall in exchange rate, however, has shown that the shocks and costs associated with such seismic market shifts may be too much to bear for many exporters.

Any effort to develop continental markets abandoned by the UK is also likely to meet fierce competition from local producers, who will need to make up for their lost British exports as well. It may be, as economist Jim Power told the Oireachtas agriculture committee last month, that Ireland’s best opportunity in a hard Brexit scenario would be to replace the €3.8bn worth of (mostly processed) British food imported here every year.

Listen to a discussion on Brexit with Co Cork dairy farmer Seán O’Lionáird in our podcast below:

Listen to “Farmer's views on Brexit” on Spreaker.

John Bruton: 'There will have to be checks that UK burgers do not contain Brazilian beef'

SHARING OPTIONS