The start of the main breeding season is around six weeks away on most spring-calving farms. A breeding start date of 25 April gives a calving start date of 30 January, presuming a 280-day gestation length.

However, many farmers are finding that some of the new high-EBI bulls have shorter gestation lengths and when used on heifers their gestation length is even shorter again. This is leading to some farmers deciding to delay the start of breeding to take account of the earlier calving.

This has a number of other benefits also. In a block-calving herd, a longer waiting period between calving and mating increases the likelihood of the cow going in calf in the first six weeks of breeding. This is because there is more time for the cow to clean out and resume ovarian cycling.

Ideally, cows should cycle twice before the start of breeding. This is why later-calving cows are harder to get back in calf.

In terms of pre-breeding animal health, the key thing is to ensure the cow is cycling before the start of mating. Cows that are not cycling won’t be served and definitely won’t go back in calf. So what can we do to ensure cows resume cycling activity quickly?

Probably the biggest single thing that farmers can do to improve the fertility performance of their herd is to ensure the cows are in good body condition score at the start of breeding. It is well proven that cows that are in the right body condition score have a much higher chance of becoming pregnant early in the breeding season.

We all know that cows are in negative energy balance after calving because their feed intake is less than their feed requirements. This causes a reduction in body condition score. Minimising this loss of condition post-calving is an important objective. It can be achieved through nutrition (feeding) and genetics (breeding).

On feeding, if the quantity and/or quality of the feed being offered is insufficient, whether that is grass, silage or meal, then more body condition will be lost as the cow mobilises fat reserves for milk production and for maintenance. Milk production will still suffer though as using body condition to produce milk is an inefficient use of energy.

Cows that lose 0.5 or more of a body condition score between calving and mating have a much reduced chance of going in calf. This is borne out in numerous research experiments both in Ireland and overseas.

So does this mean we need to feed more meal to cows for them to hold on to body condition? Not necessarily. When analysing nutrition, we need to look at the overall picture. Spring grass is by itself a complete diet. Where grass is scarce and supplemented by a few kilogrammes of meal, there shouldn’t be a problem with nutrition for most Irish herds.

Where problems do occur, is where the diet is mostly silage. In comparison with spring grass, silage is low in energy and protein. So more supplement needs to be fed with it to ensure a balanced diet.

Also, cows should be on a rising plane of nutrition in the runup to the start of the breeding season. If we think back to last season, the opposite happened on most farms because grass supply was scarce in April so extra silage had to be fed which is an inferior feed to grass. So stocking rate and calving date should be closely matched to the grass growing ability of your farm.

Issues around nutrition are compounded on higher-yielding herds where more energy is consumed producing milk.

This is where genetics come into play. Cows bred for high volumes of milk find it difficult to retain body condition because they are genetically predisposed to producing milk, so extra feed is given over to milk production, to the detriment of body condition and fertility.

On the contrary, high-EBI cows that are balanced in the milk and fertility sub-indices have a higher body condition score throughout lactation. This is one of the key findings from the Next Generation Herd study at Moorepark.

But nutrition and genetics are both medium- to long-term solutions. What about the immediate health problems in the runup to breeding? Non-cycling cows and dirty cows are the main issues.

Non-cyclers are cows that have not shown signs of heat. Some of these cows will have had silent heats that just were not observed and in more cases the heats will have been missed. However, some cows will be true anoestrus, which is, not cycling at all.

Most farmers won’t know this unless the cows are scanned. However, more and more farmers are moving away from getting these non-cycling cows scanned and are just putting them all on once-a-day milking. This has the same effect as feeding them extra meal or giving them more grass. The drop in milk output reduces their energy requirement so body condition increases.

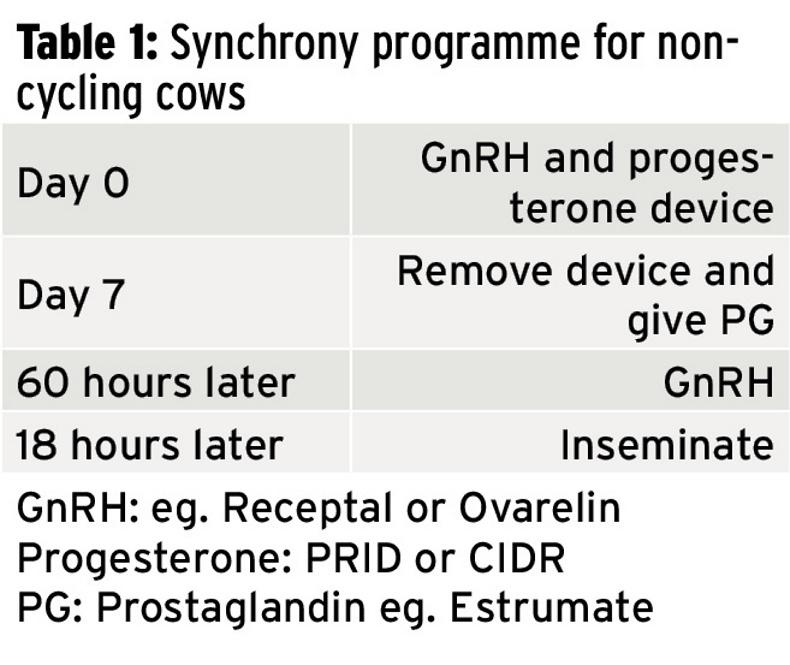

They find that a good proportion of the cows resume cycling activity after going on once-a-day milking without any need for scanning or hormone treatments. However, there are hormone treatments designed for treating non-cycling cows calved over 30 days as detailed in Table 1. This protocol is what is recommended by Teagasc for non-cycling cows and it involves the use of a progesterone device and fixed time AI, so the cow should be inseminated whether or not she shows signs of heat.

Cows that have had silent heats or missed heats don’t need the progesterone device as they are already cycling, unless fixed-time AI is desired. Therefore, all cows should be scanned by a vet to know what is what before any hormone programme is used.

Dirty cows

This is the collective term for cows with metritis, endometritis or a womb infection. This can be identified by pus coming from the vagina, a cow seen forcing or a cow with a bad smell from the rear end. The common causes are difficult calvings, retained cleanings and poor hygiene at calving.

Generally speaking, a dirty cow has an infection in the womb and depending on the severity of the infection it could be making her sick. Either way, it will vastly reduce her chances of pregnancy. She needs to be treated. Veterinary advice to treat dirty cows tends to be towards washouts with antibiotics although if a cow has a temperature, intramuscular antibiotics can also be prescribed.

There is a move away from giving iodine washouts to cows as some people say it could be doing more harm than good, particularly if used at the wrong dilution rate. Intrauterine antibiotics such as Metricure can be prescribed by a vet. Timing is important, best results are achieved when given more than 14 days after calving and repeat again after a week if necessary.

Read more

Special focus: animal health 2017

The start of the main breeding season is around six weeks away on most spring-calving farms. A breeding start date of 25 April gives a calving start date of 30 January, presuming a 280-day gestation length.

However, many farmers are finding that some of the new high-EBI bulls have shorter gestation lengths and when used on heifers their gestation length is even shorter again. This is leading to some farmers deciding to delay the start of breeding to take account of the earlier calving.

This has a number of other benefits also. In a block-calving herd, a longer waiting period between calving and mating increases the likelihood of the cow going in calf in the first six weeks of breeding. This is because there is more time for the cow to clean out and resume ovarian cycling.

Ideally, cows should cycle twice before the start of breeding. This is why later-calving cows are harder to get back in calf.

In terms of pre-breeding animal health, the key thing is to ensure the cow is cycling before the start of mating. Cows that are not cycling won’t be served and definitely won’t go back in calf. So what can we do to ensure cows resume cycling activity quickly?

Probably the biggest single thing that farmers can do to improve the fertility performance of their herd is to ensure the cows are in good body condition score at the start of breeding. It is well proven that cows that are in the right body condition score have a much higher chance of becoming pregnant early in the breeding season.

We all know that cows are in negative energy balance after calving because their feed intake is less than their feed requirements. This causes a reduction in body condition score. Minimising this loss of condition post-calving is an important objective. It can be achieved through nutrition (feeding) and genetics (breeding).

On feeding, if the quantity and/or quality of the feed being offered is insufficient, whether that is grass, silage or meal, then more body condition will be lost as the cow mobilises fat reserves for milk production and for maintenance. Milk production will still suffer though as using body condition to produce milk is an inefficient use of energy.

Cows that lose 0.5 or more of a body condition score between calving and mating have a much reduced chance of going in calf. This is borne out in numerous research experiments both in Ireland and overseas.

So does this mean we need to feed more meal to cows for them to hold on to body condition? Not necessarily. When analysing nutrition, we need to look at the overall picture. Spring grass is by itself a complete diet. Where grass is scarce and supplemented by a few kilogrammes of meal, there shouldn’t be a problem with nutrition for most Irish herds.

Where problems do occur, is where the diet is mostly silage. In comparison with spring grass, silage is low in energy and protein. So more supplement needs to be fed with it to ensure a balanced diet.

Also, cows should be on a rising plane of nutrition in the runup to the start of the breeding season. If we think back to last season, the opposite happened on most farms because grass supply was scarce in April so extra silage had to be fed which is an inferior feed to grass. So stocking rate and calving date should be closely matched to the grass growing ability of your farm.

Issues around nutrition are compounded on higher-yielding herds where more energy is consumed producing milk.

This is where genetics come into play. Cows bred for high volumes of milk find it difficult to retain body condition because they are genetically predisposed to producing milk, so extra feed is given over to milk production, to the detriment of body condition and fertility.

On the contrary, high-EBI cows that are balanced in the milk and fertility sub-indices have a higher body condition score throughout lactation. This is one of the key findings from the Next Generation Herd study at Moorepark.

But nutrition and genetics are both medium- to long-term solutions. What about the immediate health problems in the runup to breeding? Non-cycling cows and dirty cows are the main issues.

Non-cyclers are cows that have not shown signs of heat. Some of these cows will have had silent heats that just were not observed and in more cases the heats will have been missed. However, some cows will be true anoestrus, which is, not cycling at all.

Most farmers won’t know this unless the cows are scanned. However, more and more farmers are moving away from getting these non-cycling cows scanned and are just putting them all on once-a-day milking. This has the same effect as feeding them extra meal or giving them more grass. The drop in milk output reduces their energy requirement so body condition increases.

They find that a good proportion of the cows resume cycling activity after going on once-a-day milking without any need for scanning or hormone treatments. However, there are hormone treatments designed for treating non-cycling cows calved over 30 days as detailed in Table 1. This protocol is what is recommended by Teagasc for non-cycling cows and it involves the use of a progesterone device and fixed time AI, so the cow should be inseminated whether or not she shows signs of heat.

Cows that have had silent heats or missed heats don’t need the progesterone device as they are already cycling, unless fixed-time AI is desired. Therefore, all cows should be scanned by a vet to know what is what before any hormone programme is used.

Dirty cows

This is the collective term for cows with metritis, endometritis or a womb infection. This can be identified by pus coming from the vagina, a cow seen forcing or a cow with a bad smell from the rear end. The common causes are difficult calvings, retained cleanings and poor hygiene at calving.

Generally speaking, a dirty cow has an infection in the womb and depending on the severity of the infection it could be making her sick. Either way, it will vastly reduce her chances of pregnancy. She needs to be treated. Veterinary advice to treat dirty cows tends to be towards washouts with antibiotics although if a cow has a temperature, intramuscular antibiotics can also be prescribed.

There is a move away from giving iodine washouts to cows as some people say it could be doing more harm than good, particularly if used at the wrong dilution rate. Intrauterine antibiotics such as Metricure can be prescribed by a vet. Timing is important, best results are achieved when given more than 14 days after calving and repeat again after a week if necessary.

Read more

Special focus: animal health 2017

SHARING OPTIONS