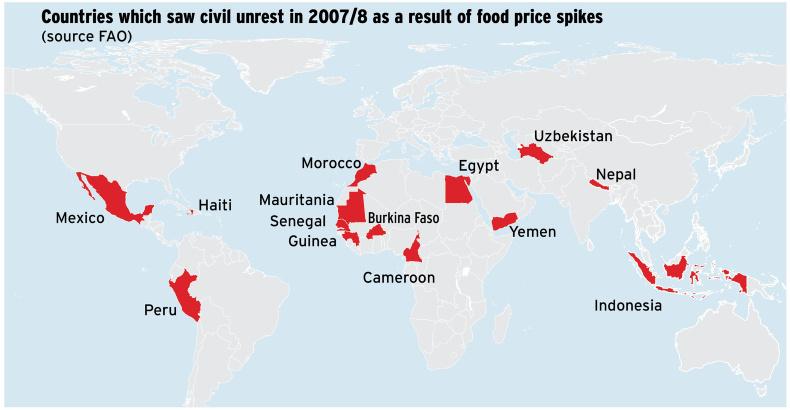

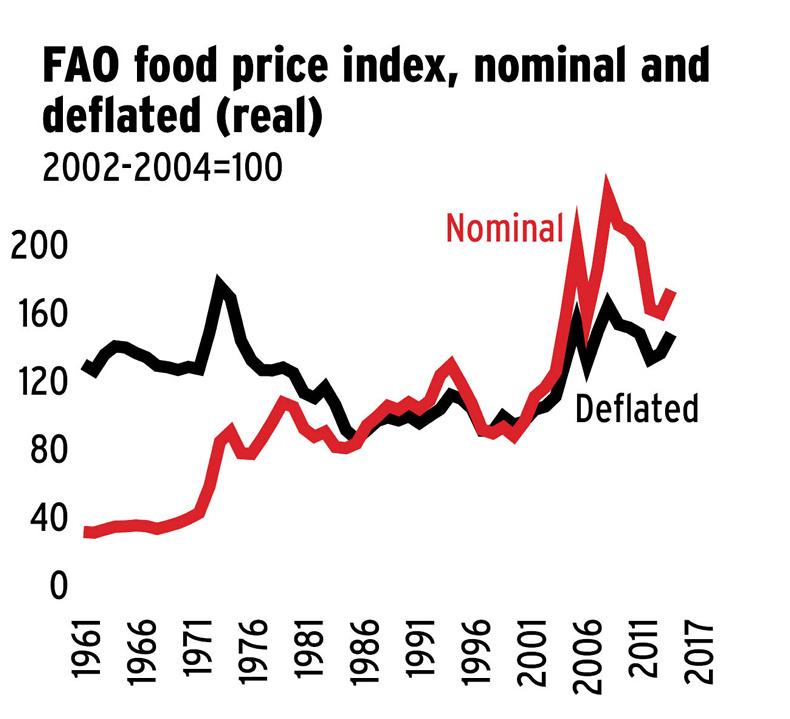

In 2007 and 2008 developing countries across the globe were shook with civil unrest, and what came to be known as the Arab spring.

Uniting the otherwise complex political and economic motivators behind these protests was a spike in food costs. Governments in developed and developing nations realised anew just how destructive hunger can be to national and international stability and started to re-examine how to make food supplies secure.

In response, Edinburgh University has specifically designed a new academy to work across the university’s departments. It is integrating the widely ranging factors – be they political, economic, medical or anthropological – which are vital to creating secure food supply systems.

“It’s about trying to get people in different parts of the university to talk together and think about how research, education and outreach could be interwoven,” Professor Geoff Simm, head of Edinburgh University’s new academy of agriculture and global food supply said.

In addition to feeding the eight million people in the world who are already starving, agriculture faces the twin challenges of rising global population (currently 7.5bn, 9bn by 2050 and 11bn by 2100 and climate change.

“In the northern hemisphere there has been less impact from climate change, but in the southern hemisphere it is massively important for agriculture.

“There will be many more mouths to feed as countries emerge from poverty seeking a western diet. This will put further pressure on livestock production, requiring more feed and more land. We haven’t got more land,” Simm says.

New technologies

Technology will help, Simm explains: “Dealing with waste throughout the system; climate-smart agriculture, precision farming, new techniques and better use of data in the value constellation, ie the supply chain, is not just about linear supply from production through to consumption. There are many side avenues including farmers markets, SMEs and online sales.”

Simm advises that we can develop new ways of producing food,but human behaviour is just as important.

“We have worked on the fact that capitalism will give all access to affordable, nutritious food. This has worked to some extent but it is not perfect: there is a ready availability of food that is not nutritious.”

Human behaviour, gender dynamics and new affluence

It is not enough to provide nutritious, affordable food Simm says, recalling a scheme which supplied chickens to families to provide eggs and meat. The men in these households saw their diet improve, but women and children did not.

“You may only see benefit when power dynamics and gender dynamics within the household are every bit as important as keeping chickens alive.”

The scourge of obesity is not just a western affliction. “In affluent African countries hip, stylish, fast-food is on the increase,” Geoff says, “I don’t think that we have recognised that well enough. Food is so deeply rooted in our culture, communities and families. These factors also apply to the 800m who are starving as well as the 2m who are obese,” Simm continues, recalling his astonishment at learning that starving and obese people are sometimes living under the same roof.

“In the global north and global south, the challenge is to re-imagine food systems that meet all of those needs: healthy diets; looking after the environment and dealing with the challenges of population growth. If we try to do it piecemeal, we will be doomed to fail.”

Importance of livestock

Professor Simm has been a “productionist” for most of his career, “looking at what happens from the farm gate to the abattoir”.

An agricultural scientist’s challenge now is about dealing with the growing demand for livestock products when we know the environmental impact of producing them. “There is great work happening on greenhouse gas emission mitigation/feeding and breeding to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

“Livestock systems developed around harvests we can’t use as humans ie grasslands, but now livestock eat cereals. We need to reconnect with that unique selling point.

“There has been a lot of negative publicity about livestock production but for the 800m people who are starving, livestock is often critical: they are a mobile production unit, a mobile bank.”

Re-imagining support

If the livestock sector has become too dependent on cereal production, humans need a balanced diet too. In Malawi, where maize and food are synonymous, governments and NGOs focused support on maize production.

“Maize is not enough to meet health requirements on its own,” Simm maintains, “it provides energy, but is deficient in micro-nutrients. Malawi has a maize culture: maize and food are synonymous. Governments and NGOs have prioritised systems which support the growing of maize and have funded important food banks to store maize. This has created impediments for developing other food markets.”

If well-intentioned but simplistic support models aren’t working, have there been any successes?

Simm cites Bóthar, a Malawi-Irish project which put in place a co-op to bulk milk.

“They put in the cows, AI, liquid nitrogen, technological advice, cow health, yoghurt production and marketing and distribution. Childhood mortality dropped from high levels to European levels,” he enthuses. The main message from the project was to put the whole chain in place.

Power

The business of power is critical. “I would like to explore how agriculture can be commercialised in a way that can keep communities involved, Simm reveals. “It is about encouraging entrepreneurship and small enterprises. This is probably every bit as important as emulating classical models of agriculture.”

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: