Last week, we had the Bord Bia report on the performance of the Irish agri-food industry for 2017. The beef industry posted a record performance with €2.5bn of exports. This week, we investigate what factories paid farmers in 2017 for steers, cows and heifers and rank the performance in each category comparing them with 2016.

The ranking of Irish factories is based on the prices reported every week to Brussels through the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine. This is required by law for all factories killing over 20,000 cattle annually and it takes place across all EU countries, enabling the EU to know the price of beef in each member country.

The information is aggregated to publish a weekly price for each country. In Ireland, the Irish Farmers Journal publishes this information for each factory for a selection of grades from all categories of cattle.

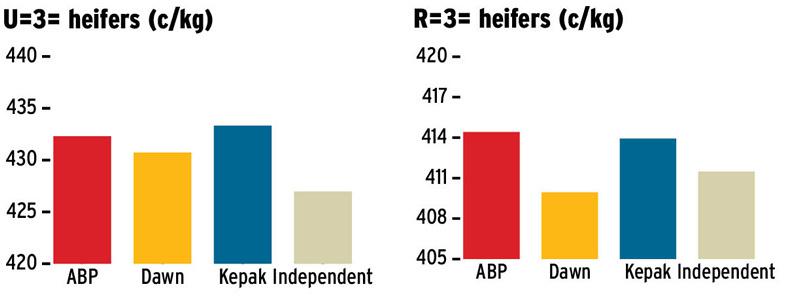

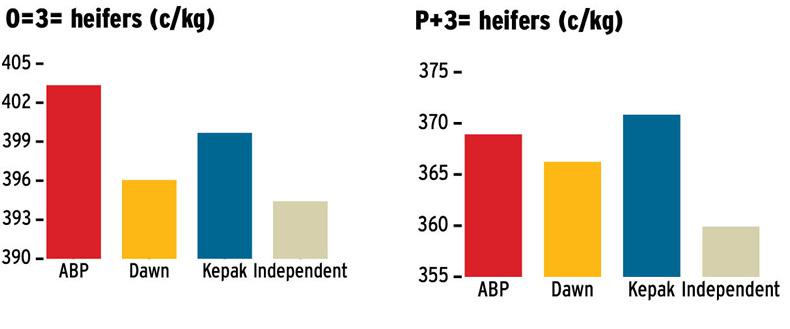

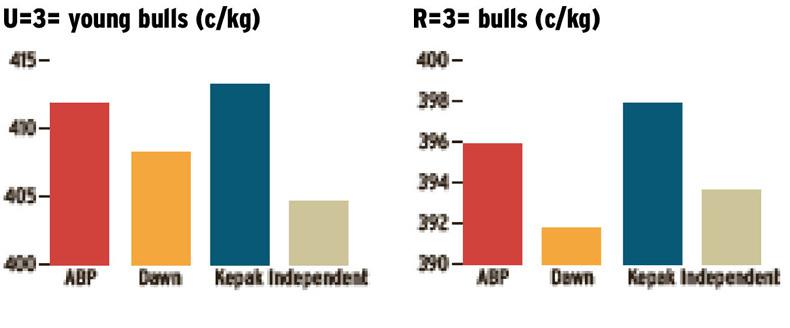

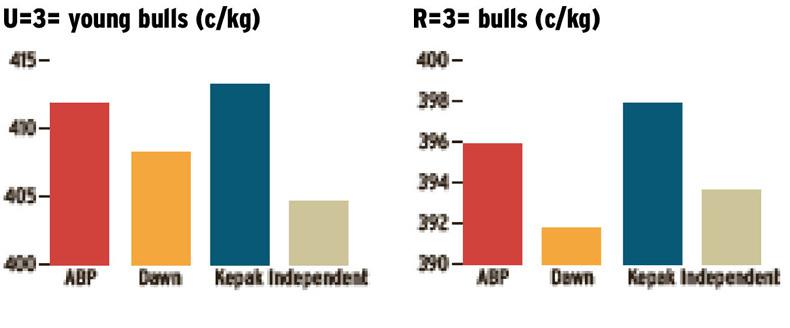

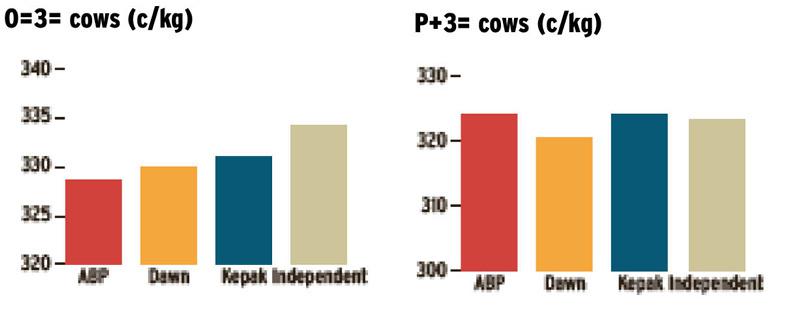

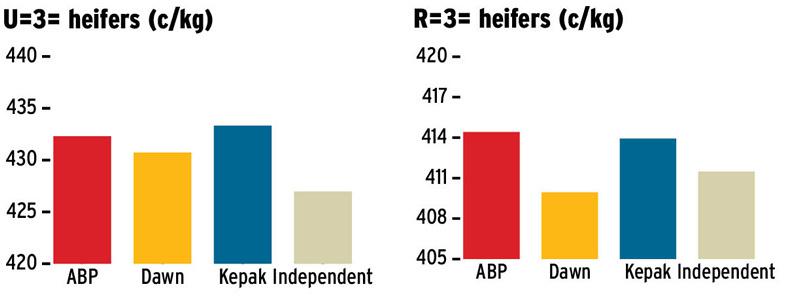

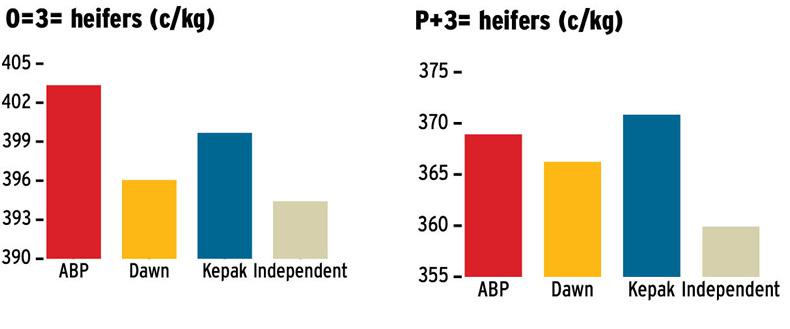

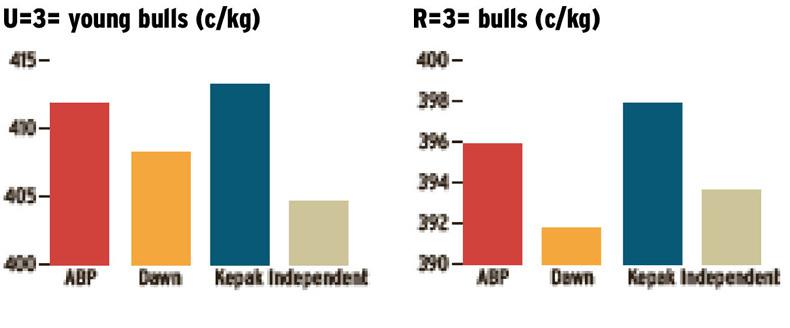

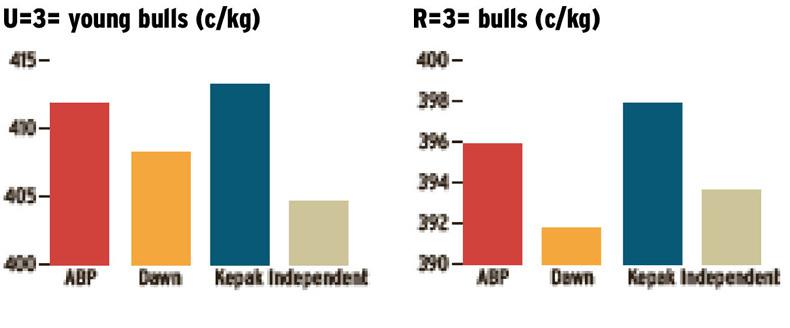

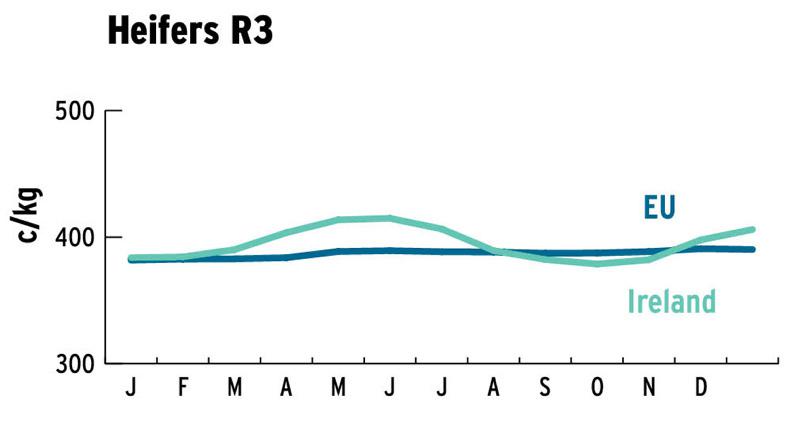

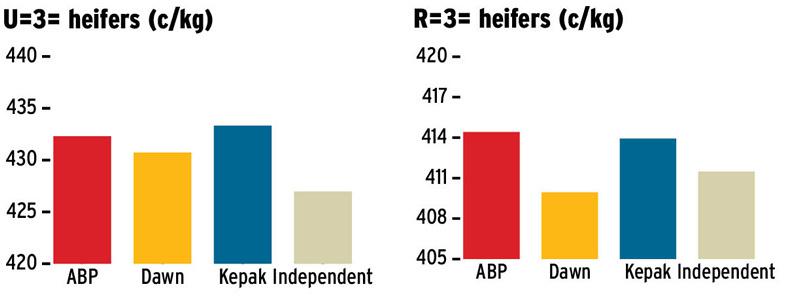

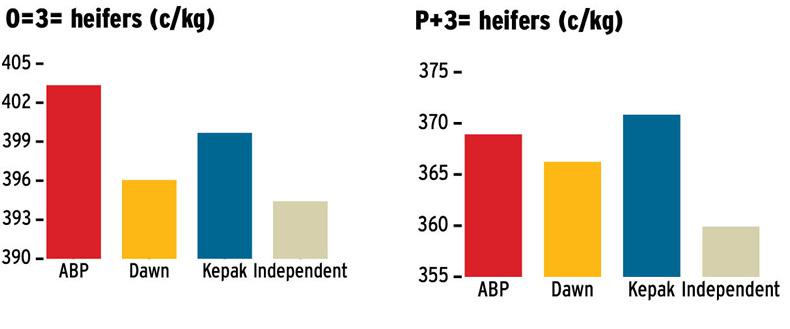

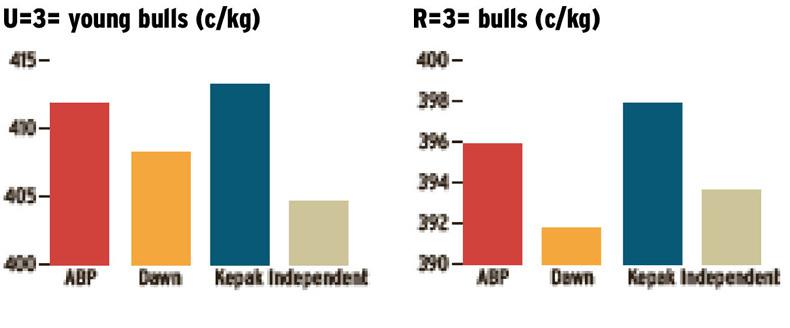

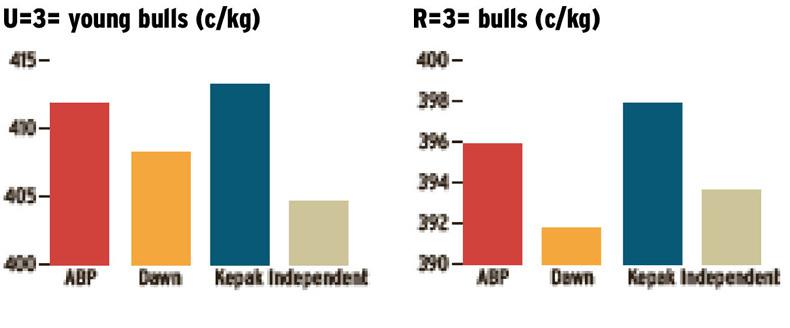

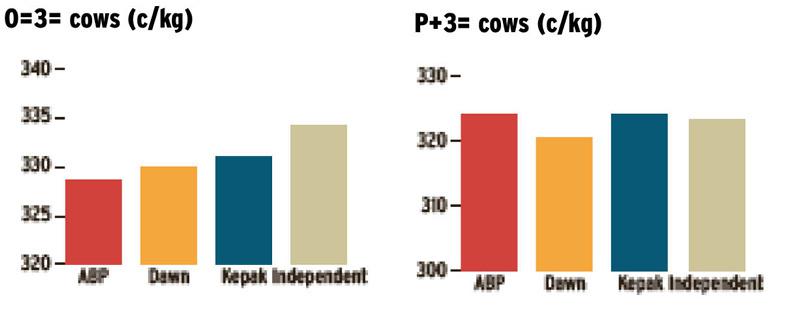

The midpoint of each grade has been selected as a representative sample, so it is U=3=, R=3=, O=3= and P+3= for steers, heifers, young bulls and cows. VAT is included at 5.4%, and the position of the factories for each category in 2016 is included in the third column.

What is used to decide price? Factories pay for cattle on the basis of dressed carcase weight. This is the beef carcase after the hide and internal organs are removed, leaving the meat, bones and most of the fat cover as some fat trimming, is permissible before the animal is weighed and graded by the video imaging analysis (VIA).

Most of the parts that are removed before the animal is weighed have a value that is captured by the factory as part of its revenue stream. This is somewhat contentious in that it is separated from the price paid to the farmer which is based on an amount per kilo for the weight of the carcase.

The counter argument is that the value realised from the hide and offal is reflected in the price paid for the carcase.

The other issues that determine the price per kilo for cattle is the shape and fat covering of the carcase which is determined by the VIA grading. The shape of the carcase is scored on the EUROP scale with E being the best, U and R are the top commercial grades with plainer cattle scoring O and P grades. Fat is measured on a scale between 1 and 5, with 3 and 4L the preferred level of cover.

Role of specifications

Not all cattle with the same grade are equal in the marketplace with the value ultimately decided by what markets the beef from each carcase can be sold. Therefore, quality assurance and weight specification affect the price paid. The fussiest customers for beef in the supermarket or burger chain trade often want to know age limits and the number of farms the animal has been on over its life, as well as insisting on quality assurance. Many export markets outside Europe will only accept beef from carcases under 30 months as a legacy of BSE even though that was an issue from 20 years ago.

What doesn’t make sense to farmers is that penalties for what are considered out-of-spec cattle are arbitrary. In 2017, when beef in general was a much stronger trade than the previous year, much less attention was paid by factories to specification.

How animals get top prices

The problem with reporting average prices is that it is just a number that is a calculated figure based on different prices that were paid by the factory for that particular grade. Therefore, in practice, it means that some cattle will have been bought above the average price while others will have been bought below it.

We have listed the specification issues that could lead to prices being cut. Factors that can result in factories paying above the “going’’ quoted price are where there are particular lots of in-spec cattle, where the cattle are bought on a contract feeding arrangement or indeed increasingly where the factory used cattle from its own feedlots. These will typically secure a higher price than is quoted to individual farmers with small lots of cattle to sell.

The price per kilo paid by factories is also influenced by the number of niche cattle that make up a week’s kill. Breeds such as Hereford, Angus and, more recently, Shorthorn command a higher rate per kilo, which varies depending on the time of year. Where there are a significant number of these in a factory’s kill in a particular week, they will push up the overall reported price in a way that doesn’t reflect what is being paid for the mainstream cattle.

The other significant niche is organic cattle which though few in number overall, have the same potential to increase the overall average where a significant number are included in a factory’s kill.

Feedlot and contract cattle are often paid a premium by factories to guarantee a supply in expected times of scarcity. Although not as big an issue in 2017 as the previous year, factories paying more usually have tighter specifications on issues of residency, quality assurance and weight. Where factories have no cattle killed in a particular category, they are not listed in the tables.Where a small number of cattle are killed in a factory in a particular category, it can unduly influence the price reported either upwards or downwards.The statistics on their own can be misleading. Farmers need to understand what exactly the factory will accept and what it will penalise for and match their cattle with a factory accordingly.Price difference per animal based on average carcase weight multiplied by difference in top and bottom price. 2017 average weights

Steers 353kgYoung bulls 365kgHeifers 312kgCows 313kg

Source: Bord Bia

How Ireland compares with other EU countries

The benchmark for the performance of Irish beef factories is comparing their prices with those paid elsewhere in the EU, in particular in the main markets to which Ireland exports beef. Space doesn’t permit analysis of Irish prices against individual countries so the EU average has been used to demonstrate overall trends during 2017. As steer beef production is largely confined to Britain and Ireland, EU young bull prices are used for comparison.

Steers and young bulls

Steer prices began 2017 around 15c/kg behind the EU young bull price but this was reversed into the spring and early summer to a point where Irish R3 steer prices climbed to over 30c/kg more than the EU average.

From June until October, Irish steer prices fell while the EU average remained steady over the summer, and increased progressively during the autumn.

A surge in Irish prices late in 2017 closed the gap to Irish R3 steers being worth 12c/kg below the average for R3 young bulls.

As for Irish young bulls, there was a period between April and July when Irish young bull prices were ahead of the EU average, by up to 40c/kg in May. However, a sharp downturn in Irish prices over the summer and early autumn was not reflected elsewhere in Europe, meaning that Irish R3 young bull prices closed the year 16c/kg behind the EU average on the R3 grade.

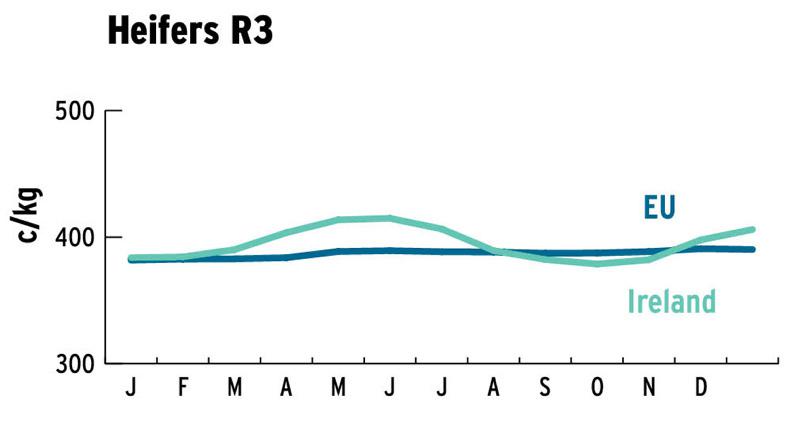

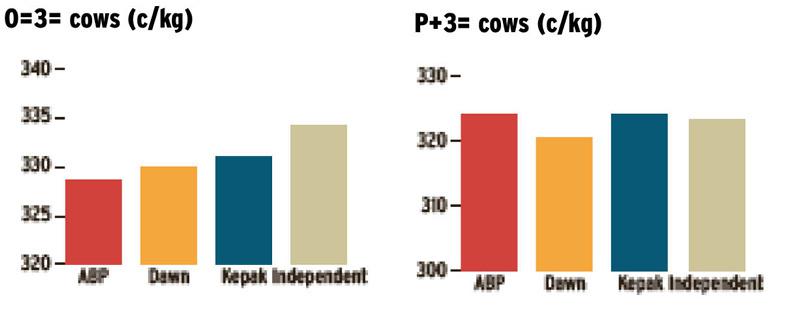

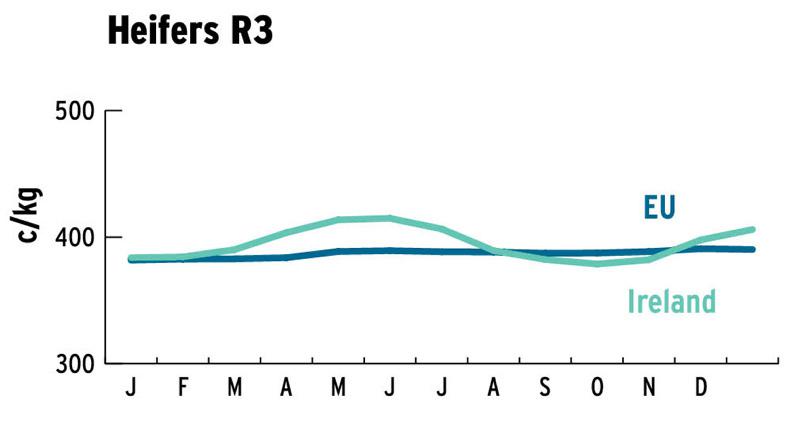

Heifers

Irish R3 heifer prices are much more aligned with their EU counterparts than steers are with young bulls. Irish heifer prices began the year 2c/kg ahead of the EU average on R3 grades and they continued ahead by varying amounts up to September when they slipped behind the EU average.

The widest gap was 9c/kg in October but, by the end of the year, rising Irish prices had moved the Irish R3 average 7c/kg ahead of the EU average again.

Cows

Cows are the category where Irish factories consistently outperform their EU counterparts, and Ireland is usually only behind France in prices paid for cows.

Irish O3 cow prices opened 2017 17c/kg ahead of the EU average and this gap proceeded to widen as the year progressed. It reached 40c/kg by May 2017 and while the gap reduced in the following months, it widened again in the latter months of the year with Irish prices 32c/kg ahead of the EU average on O3 grade cows at the end of the year.

Read more

What role does offal play in the price of beef

Beef trends: factories closely managing throughput

Last week, we had the Bord Bia report on the performance of the Irish agri-food industry for 2017. The beef industry posted a record performance with €2.5bn of exports. This week, we investigate what factories paid farmers in 2017 for steers, cows and heifers and rank the performance in each category comparing them with 2016.

The ranking of Irish factories is based on the prices reported every week to Brussels through the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine. This is required by law for all factories killing over 20,000 cattle annually and it takes place across all EU countries, enabling the EU to know the price of beef in each member country.

The information is aggregated to publish a weekly price for each country. In Ireland, the Irish Farmers Journal publishes this information for each factory for a selection of grades from all categories of cattle.

The midpoint of each grade has been selected as a representative sample, so it is U=3=, R=3=, O=3= and P+3= for steers, heifers, young bulls and cows. VAT is included at 5.4%, and the position of the factories for each category in 2016 is included in the third column.

What is used to decide price? Factories pay for cattle on the basis of dressed carcase weight. This is the beef carcase after the hide and internal organs are removed, leaving the meat, bones and most of the fat cover as some fat trimming, is permissible before the animal is weighed and graded by the video imaging analysis (VIA).

Most of the parts that are removed before the animal is weighed have a value that is captured by the factory as part of its revenue stream. This is somewhat contentious in that it is separated from the price paid to the farmer which is based on an amount per kilo for the weight of the carcase.

The counter argument is that the value realised from the hide and offal is reflected in the price paid for the carcase.

The other issues that determine the price per kilo for cattle is the shape and fat covering of the carcase which is determined by the VIA grading. The shape of the carcase is scored on the EUROP scale with E being the best, U and R are the top commercial grades with plainer cattle scoring O and P grades. Fat is measured on a scale between 1 and 5, with 3 and 4L the preferred level of cover.

Role of specifications

Not all cattle with the same grade are equal in the marketplace with the value ultimately decided by what markets the beef from each carcase can be sold. Therefore, quality assurance and weight specification affect the price paid. The fussiest customers for beef in the supermarket or burger chain trade often want to know age limits and the number of farms the animal has been on over its life, as well as insisting on quality assurance. Many export markets outside Europe will only accept beef from carcases under 30 months as a legacy of BSE even though that was an issue from 20 years ago.

What doesn’t make sense to farmers is that penalties for what are considered out-of-spec cattle are arbitrary. In 2017, when beef in general was a much stronger trade than the previous year, much less attention was paid by factories to specification.

How animals get top prices

The problem with reporting average prices is that it is just a number that is a calculated figure based on different prices that were paid by the factory for that particular grade. Therefore, in practice, it means that some cattle will have been bought above the average price while others will have been bought below it.

We have listed the specification issues that could lead to prices being cut. Factors that can result in factories paying above the “going’’ quoted price are where there are particular lots of in-spec cattle, where the cattle are bought on a contract feeding arrangement or indeed increasingly where the factory used cattle from its own feedlots. These will typically secure a higher price than is quoted to individual farmers with small lots of cattle to sell.

The price per kilo paid by factories is also influenced by the number of niche cattle that make up a week’s kill. Breeds such as Hereford, Angus and, more recently, Shorthorn command a higher rate per kilo, which varies depending on the time of year. Where there are a significant number of these in a factory’s kill in a particular week, they will push up the overall reported price in a way that doesn’t reflect what is being paid for the mainstream cattle.

The other significant niche is organic cattle which though few in number overall, have the same potential to increase the overall average where a significant number are included in a factory’s kill.

Feedlot and contract cattle are often paid a premium by factories to guarantee a supply in expected times of scarcity. Although not as big an issue in 2017 as the previous year, factories paying more usually have tighter specifications on issues of residency, quality assurance and weight. Where factories have no cattle killed in a particular category, they are not listed in the tables.Where a small number of cattle are killed in a factory in a particular category, it can unduly influence the price reported either upwards or downwards.The statistics on their own can be misleading. Farmers need to understand what exactly the factory will accept and what it will penalise for and match their cattle with a factory accordingly.Price difference per animal based on average carcase weight multiplied by difference in top and bottom price. 2017 average weights

Steers 353kgYoung bulls 365kgHeifers 312kgCows 313kg

Source: Bord Bia

How Ireland compares with other EU countries

The benchmark for the performance of Irish beef factories is comparing their prices with those paid elsewhere in the EU, in particular in the main markets to which Ireland exports beef. Space doesn’t permit analysis of Irish prices against individual countries so the EU average has been used to demonstrate overall trends during 2017. As steer beef production is largely confined to Britain and Ireland, EU young bull prices are used for comparison.

Steers and young bulls

Steer prices began 2017 around 15c/kg behind the EU young bull price but this was reversed into the spring and early summer to a point where Irish R3 steer prices climbed to over 30c/kg more than the EU average.

From June until October, Irish steer prices fell while the EU average remained steady over the summer, and increased progressively during the autumn.

A surge in Irish prices late in 2017 closed the gap to Irish R3 steers being worth 12c/kg below the average for R3 young bulls.

As for Irish young bulls, there was a period between April and July when Irish young bull prices were ahead of the EU average, by up to 40c/kg in May. However, a sharp downturn in Irish prices over the summer and early autumn was not reflected elsewhere in Europe, meaning that Irish R3 young bull prices closed the year 16c/kg behind the EU average on the R3 grade.

Heifers

Irish R3 heifer prices are much more aligned with their EU counterparts than steers are with young bulls. Irish heifer prices began the year 2c/kg ahead of the EU average on R3 grades and they continued ahead by varying amounts up to September when they slipped behind the EU average.

The widest gap was 9c/kg in October but, by the end of the year, rising Irish prices had moved the Irish R3 average 7c/kg ahead of the EU average again.

Cows

Cows are the category where Irish factories consistently outperform their EU counterparts, and Ireland is usually only behind France in prices paid for cows.

Irish O3 cow prices opened 2017 17c/kg ahead of the EU average and this gap proceeded to widen as the year progressed. It reached 40c/kg by May 2017 and while the gap reduced in the following months, it widened again in the latter months of the year with Irish prices 32c/kg ahead of the EU average on O3 grade cows at the end of the year.

Read more

What role does offal play in the price of beef

Beef trends: factories closely managing throughput

SHARING OPTIONS