Zak Moradi is a man with strong roots and many wide-reaching branches. In a way, he’s both a country boy and a city slicker.

First and foremost, he’s from Kurdistan in Iran. Speaking with Zak, his Kurdish-Iranian culture organically permeates every conversation.

His people are of the countryside – farmers. However, he wasn’t born on a farm in the Iranian mountains as his parents were, but in the city of Ramadi, Iraq. His parents fled there in 1980 during the Iran-Iraq War.

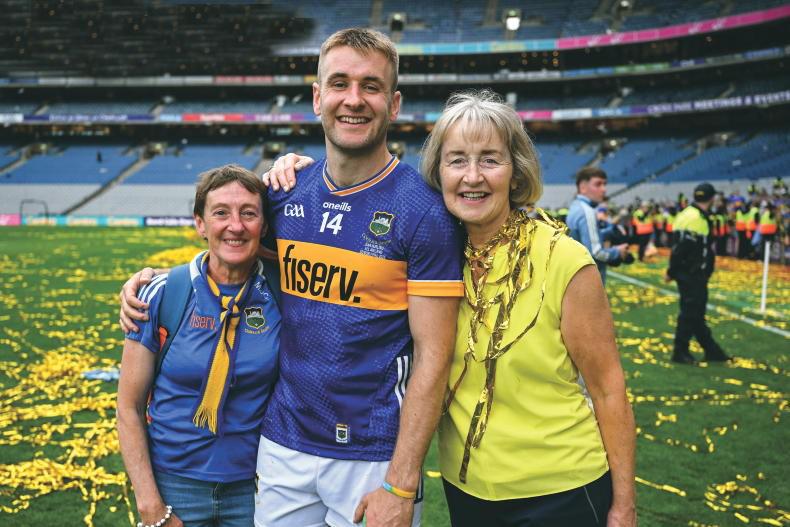

Zak Moradi was born in Iraq, but is Kurdish-Iranian. \ Philip Doyle

Again, when Zak and his family moved to Ireland in 2002, it was in a more rural location they laid foundations, Carrick-on-Shannon, Co Leitrim. Some years later his whole family relocated to Dublin. Showing both his roots and branches, Zak played county hurling for Leitrim for years – this is his first year not playing with the county – but he still plays club hurling for Thomas Davis in Dublin.

Zak lives in Tallaght, but is keeping some of his family’s farming background alive. He works for Zoetis, a company that produce medicine for pets and livestock. Or, as he says himself: “We make teat seal for the cows.” Spoken like a true farmer!

To get all our ducks in a row from the off, Zak’s name is actually Semaco. Like many when he moved to Ireland, he acquired an alias that stuck.

Next year Zak will be 20 years living in Ireland. Most of those years have been spent living in Dublin. He lived in Carrick for just two. All the same, he will always be known as “the Leitrim hurler”. The nippy corner forward that was part of the 2019 Lory Meagher-winning team, elevating Leitrim to Nicky Rackard status.

Even from just this snapshot of Zak’s life to date, it’s clear that his story is a quite remarkable one. So let’s hear it in a bit more detail, shall we?

Culture shock

As mentioned already, although Zak and his family are Iranian, he was born in Iraq. With eight brothers and two sisters, some of his siblings were born in Iran and the others in Iraq. Zak starts his story by explaining that growing up under the Saddam Hussein regime was a completely different experience to growing up in Ireland.

Zak Moradi's family are farmers in Iran. \ Philip Doyle

One of the world’s largest oil producers, Iraq is a wealthy country for some, Zak explains. “People in Ramadi lived in mansions, because Iraq is a very wealthy country. The rich are rich. In Iraq there are oil fields everywhere, but conflict and war have the country destroyed. As they say, you don’t know what Iraq is going to be like in 30 years. You go to certain parts of Iraq and it’s like Paris in France.

“We only went to school for two or three hours a day really, that was it. It’d all be propaganda stuff about the regime. The [then-] leader of Iraq (Saddam Hussein), he ruled with an iron fist. It was his way or no way. It was all about him. No one could speak up, if you spoke up you were put in prison. Your whole family were in, you’d never get out.”

After 9/11 and subsequent invasion of Iraq by the US, the Moradis decided to leave. You went where the UN could send you, Zak recalls. Ireland wasn’t very much on 11-year-old Zak’s radar.

“I didn’t really know where I was going, I’ll be honest,” Zak reflects. “I thought we were going to England. I just knew we were getting out of there. We were going to Europe, that was the thing. We were brought up in a dictatorship, you didn’t know the difference when you grow up in a country where everyone’s brainwashed.”

The 13 Moradis (mam, dad and 11 children) had been travelling for three days when they finally landed in Leitrim on 1 July 2002. For Zak, it was a huge change.

“It was a massive surprise obviously,” Zak says. “You’re growing up in a country where you’re surrounded by oil fields – the smell of smoke and oil – it’s like a desert basically we were in, then here it’s full of rain and green.

“I’d say the first week it was very hard to settle in, because you’re just on a different planet. You’re tired, you obviously don’t know what’s going on. At same time though it was fun and exciting, but you miss your family members, your cousins that were left behind. In the end, everyone I grew up with, they all ended up in Europe.”

Zak Moradi works for Zoetis. \ Philip Doyle

Almost immediately, Zak and his siblings began to make friends. He had no English coming to Ireland, but picked it up quickly. That September he started primary school in Leitrim and it was there he discovered the GAA. Zak was always sporty. Back in Iraq he played soccer and volleyball, whatever was happening, really. First he played football in school and then took to hurling, going on to join a local club.

When Zak moved to Dublin two years later, joining Thomas Davis was a great way to make friends. He has been at the club ever since.

“Living in Leitrim, it was a great time. I remember I missed it. I still have friends over there in Leitrim I meet up with all the time. Even though I’m finished playing with them, I went down a couple of weekends ago and had a few pints. The lads were playing a match and I went down to watch.”

Little and large

When to comes to the conversation around the advantages bigger counties have over smaller counties in the GAA, I observe that Zak has a unique perspective; having playing links with both the county with the smallest and largest populations. It’s a topic he doesn’t shy away from.

People say money is not going to win you an All-Ireland, but money can put you in a good place

“A lot of it has got to do with funding,” Zak begins. “Funding is a big issue as well. It wasn’t like this 30 years ago when Leitrim were getting to an All-Ireland semi-final and winning Connaught, because it wasn’t about money and sponsorship.

“Now you’ve got money involved. People say money is not going to win you an All-Ireland, but money can put you in a good place, a good set-up and get you the best of facilities. If there’s money there, if there’s funding there, the players don’t have to worry about fundraising, they can concentrate on playing.”

When it comes to fundraising and sponsors, Zak has played his part in spades. This year the Leitrim hurling jersey carries the slogan No to Racism, a campaign in partnership with the Migrant Rights Centre Ireland (MRCI), the launch of which Zak was involved with.

On a more grassroots level, Zak also secured sponsorship for tops in the famous Ryan’s Bar on Camden St in Dublin in the wee hours of the morning once. For those of you who don’t know, Ryan’s is a Mecca for ag students and country people in Dublin. Its owners are from Tipp, but the main man on the door, Peter, is from Leitrim.

Even the owners, they have no connection to Leitrim, but that’s what the GAA is all about, helping out

“I go into Ryan’s a good bit before and after the matches. Peter, he’s from Leitrim originally and in all fairness to the owners – they’re from Tipp – they helped out there with the Leitrim hurlers a couple of years ago. They gave us a couple of quid so you couldn’t complain. Even the owners, they have no connection to Leitrim, but that’s what the GAA is all about, helping out.”

For counties like Leitrim, Zak says it’s important to get outside investment, as there are less companies and businesses within the county. He references the sponsor of the Leitrim footballers, PJ Clarke’s, a pub owned by Leitrim natives in New York.

Farming the world over

Although initially to Zak the world’s he inhabited seemed very different when he first came to Ireland, he feels now the Kurds and the Irish have plenty in common. Kurdish traditional music, although it sounds slightly different, uses similar instruments to Irish trad music.

He speaks Kurdish at home with his family and notices now that the next generation – his nieces and nephews – tend to mix in English words, as Irish speakers in the Gaeltacht often do. Farmers are one and the same also, he says.

That’s their livelihood and they love it as well. That’s their bread and butter. They’ve made a living out of it

When Zak visited his native homeland in Iran a number of years ago, he experienced the life his parents would have lived firsthand. His uncles are all in different enterprises, from sheep to goats, vegetable growing and bees.

“My uncles, they’re still farmers from head to toe,” Zak laughs. “That’s their livelihood and they love it as well. That’s their bread and butter. They’ve made a living out of it. They’ve been doing very well for themselves.”

With farming, no matter where you are in the world, there are parallels, Zak feels.

“Over there reminds me a bit of down the country here. The farmer has a house, the kids grow up and they live on the farm. It’s no different over there as well, it’s the same thing. It’s amazing, a lot of farmers they have the same mentality. It’s no different over there. I’ve visited over there and I’ve seen it.

Where they are, the whole area is just full of agriculture

“What I noticed is that they’re happy, but they’ll always be giving out. Typical farmers,” Zak says, tongue in cheek, of course! “They’re always giving out about prices. They’re not selling their cucumbers for enough. They’re not selling their tomatoes enough.

“Where they are, the whole area is just full of agriculture. In Iran farming is massive. I’d say they feed the whole of Iraq. There’s very little farming in Iraq. My cousin does a lot of exporting of fruit and veg to Kurdistan of Iraq. He does very well out of it, but the odd time he’d be complaining as well,” Zak laughs.

I love where I come from. You have to be proud of where you come from

Really, whether it’s Iranian farming or hurling in Leitrim, living in Ramadi or working in Dublin, Zak’s roots are intertwined and his branches grow together.

“I love where I come from. You have to be proud of where you come from. The same as any other Irish person you meet around the world, they’re always proud of where they come from. We’d be the same as well.”

Kurdish people are an Iranian ethnic group who live a mountainous region known as Kurdistan. Kurdistan stretches across part of Iran, Iraq, Turkey and Syria.

Read more

Podcast: Franz Sauerland on Gaeilge, football and experiencing racial abuse

Zak Moradi is a man with strong roots and many wide-reaching branches. In a way, he’s both a country boy and a city slicker.

First and foremost, he’s from Kurdistan in Iran. Speaking with Zak, his Kurdish-Iranian culture organically permeates every conversation.

His people are of the countryside – farmers. However, he wasn’t born on a farm in the Iranian mountains as his parents were, but in the city of Ramadi, Iraq. His parents fled there in 1980 during the Iran-Iraq War.

Zak Moradi was born in Iraq, but is Kurdish-Iranian. \ Philip Doyle

Again, when Zak and his family moved to Ireland in 2002, it was in a more rural location they laid foundations, Carrick-on-Shannon, Co Leitrim. Some years later his whole family relocated to Dublin. Showing both his roots and branches, Zak played county hurling for Leitrim for years – this is his first year not playing with the county – but he still plays club hurling for Thomas Davis in Dublin.

Zak lives in Tallaght, but is keeping some of his family’s farming background alive. He works for Zoetis, a company that produce medicine for pets and livestock. Or, as he says himself: “We make teat seal for the cows.” Spoken like a true farmer!

To get all our ducks in a row from the off, Zak’s name is actually Semaco. Like many when he moved to Ireland, he acquired an alias that stuck.

Next year Zak will be 20 years living in Ireland. Most of those years have been spent living in Dublin. He lived in Carrick for just two. All the same, he will always be known as “the Leitrim hurler”. The nippy corner forward that was part of the 2019 Lory Meagher-winning team, elevating Leitrim to Nicky Rackard status.

Even from just this snapshot of Zak’s life to date, it’s clear that his story is a quite remarkable one. So let’s hear it in a bit more detail, shall we?

Culture shock

As mentioned already, although Zak and his family are Iranian, he was born in Iraq. With eight brothers and two sisters, some of his siblings were born in Iran and the others in Iraq. Zak starts his story by explaining that growing up under the Saddam Hussein regime was a completely different experience to growing up in Ireland.

Zak Moradi's family are farmers in Iran. \ Philip Doyle

One of the world’s largest oil producers, Iraq is a wealthy country for some, Zak explains. “People in Ramadi lived in mansions, because Iraq is a very wealthy country. The rich are rich. In Iraq there are oil fields everywhere, but conflict and war have the country destroyed. As they say, you don’t know what Iraq is going to be like in 30 years. You go to certain parts of Iraq and it’s like Paris in France.

“We only went to school for two or three hours a day really, that was it. It’d all be propaganda stuff about the regime. The [then-] leader of Iraq (Saddam Hussein), he ruled with an iron fist. It was his way or no way. It was all about him. No one could speak up, if you spoke up you were put in prison. Your whole family were in, you’d never get out.”

After 9/11 and subsequent invasion of Iraq by the US, the Moradis decided to leave. You went where the UN could send you, Zak recalls. Ireland wasn’t very much on 11-year-old Zak’s radar.

“I didn’t really know where I was going, I’ll be honest,” Zak reflects. “I thought we were going to England. I just knew we were getting out of there. We were going to Europe, that was the thing. We were brought up in a dictatorship, you didn’t know the difference when you grow up in a country where everyone’s brainwashed.”

The 13 Moradis (mam, dad and 11 children) had been travelling for three days when they finally landed in Leitrim on 1 July 2002. For Zak, it was a huge change.

“It was a massive surprise obviously,” Zak says. “You’re growing up in a country where you’re surrounded by oil fields – the smell of smoke and oil – it’s like a desert basically we were in, then here it’s full of rain and green.

“I’d say the first week it was very hard to settle in, because you’re just on a different planet. You’re tired, you obviously don’t know what’s going on. At same time though it was fun and exciting, but you miss your family members, your cousins that were left behind. In the end, everyone I grew up with, they all ended up in Europe.”

Zak Moradi works for Zoetis. \ Philip Doyle

Almost immediately, Zak and his siblings began to make friends. He had no English coming to Ireland, but picked it up quickly. That September he started primary school in Leitrim and it was there he discovered the GAA. Zak was always sporty. Back in Iraq he played soccer and volleyball, whatever was happening, really. First he played football in school and then took to hurling, going on to join a local club.

When Zak moved to Dublin two years later, joining Thomas Davis was a great way to make friends. He has been at the club ever since.

“Living in Leitrim, it was a great time. I remember I missed it. I still have friends over there in Leitrim I meet up with all the time. Even though I’m finished playing with them, I went down a couple of weekends ago and had a few pints. The lads were playing a match and I went down to watch.”

Little and large

When to comes to the conversation around the advantages bigger counties have over smaller counties in the GAA, I observe that Zak has a unique perspective; having playing links with both the county with the smallest and largest populations. It’s a topic he doesn’t shy away from.

People say money is not going to win you an All-Ireland, but money can put you in a good place

“A lot of it has got to do with funding,” Zak begins. “Funding is a big issue as well. It wasn’t like this 30 years ago when Leitrim were getting to an All-Ireland semi-final and winning Connaught, because it wasn’t about money and sponsorship.

“Now you’ve got money involved. People say money is not going to win you an All-Ireland, but money can put you in a good place, a good set-up and get you the best of facilities. If there’s money there, if there’s funding there, the players don’t have to worry about fundraising, they can concentrate on playing.”

When it comes to fundraising and sponsors, Zak has played his part in spades. This year the Leitrim hurling jersey carries the slogan No to Racism, a campaign in partnership with the Migrant Rights Centre Ireland (MRCI), the launch of which Zak was involved with.

On a more grassroots level, Zak also secured sponsorship for tops in the famous Ryan’s Bar on Camden St in Dublin in the wee hours of the morning once. For those of you who don’t know, Ryan’s is a Mecca for ag students and country people in Dublin. Its owners are from Tipp, but the main man on the door, Peter, is from Leitrim.

Even the owners, they have no connection to Leitrim, but that’s what the GAA is all about, helping out

“I go into Ryan’s a good bit before and after the matches. Peter, he’s from Leitrim originally and in all fairness to the owners – they’re from Tipp – they helped out there with the Leitrim hurlers a couple of years ago. They gave us a couple of quid so you couldn’t complain. Even the owners, they have no connection to Leitrim, but that’s what the GAA is all about, helping out.”

For counties like Leitrim, Zak says it’s important to get outside investment, as there are less companies and businesses within the county. He references the sponsor of the Leitrim footballers, PJ Clarke’s, a pub owned by Leitrim natives in New York.

Farming the world over

Although initially to Zak the world’s he inhabited seemed very different when he first came to Ireland, he feels now the Kurds and the Irish have plenty in common. Kurdish traditional music, although it sounds slightly different, uses similar instruments to Irish trad music.

He speaks Kurdish at home with his family and notices now that the next generation – his nieces and nephews – tend to mix in English words, as Irish speakers in the Gaeltacht often do. Farmers are one and the same also, he says.

That’s their livelihood and they love it as well. That’s their bread and butter. They’ve made a living out of it

When Zak visited his native homeland in Iran a number of years ago, he experienced the life his parents would have lived firsthand. His uncles are all in different enterprises, from sheep to goats, vegetable growing and bees.

“My uncles, they’re still farmers from head to toe,” Zak laughs. “That’s their livelihood and they love it as well. That’s their bread and butter. They’ve made a living out of it. They’ve been doing very well for themselves.”

With farming, no matter where you are in the world, there are parallels, Zak feels.

“Over there reminds me a bit of down the country here. The farmer has a house, the kids grow up and they live on the farm. It’s no different over there as well, it’s the same thing. It’s amazing, a lot of farmers they have the same mentality. It’s no different over there. I’ve visited over there and I’ve seen it.

Where they are, the whole area is just full of agriculture

“What I noticed is that they’re happy, but they’ll always be giving out. Typical farmers,” Zak says, tongue in cheek, of course! “They’re always giving out about prices. They’re not selling their cucumbers for enough. They’re not selling their tomatoes enough.

“Where they are, the whole area is just full of agriculture. In Iran farming is massive. I’d say they feed the whole of Iraq. There’s very little farming in Iraq. My cousin does a lot of exporting of fruit and veg to Kurdistan of Iraq. He does very well out of it, but the odd time he’d be complaining as well,” Zak laughs.

I love where I come from. You have to be proud of where you come from

Really, whether it’s Iranian farming or hurling in Leitrim, living in Ramadi or working in Dublin, Zak’s roots are intertwined and his branches grow together.

“I love where I come from. You have to be proud of where you come from. The same as any other Irish person you meet around the world, they’re always proud of where they come from. We’d be the same as well.”

Kurdish people are an Iranian ethnic group who live a mountainous region known as Kurdistan. Kurdistan stretches across part of Iran, Iraq, Turkey and Syria.

Read more

Podcast: Franz Sauerland on Gaeilge, football and experiencing racial abuse

SHARING OPTIONS