The decision by the UK government to bring forward legislation to overrule the Northern Ireland (NI) protocol could effectively remove NI from the EU single market.

This, in turn, effectively closes cross-border markets to NI farmers.

Most exposed if this happened are dairy farmers, who have 800m litres or one-third of total NI production processed in dairies south of the border.

NI sheep farmers would also be hit, as they send up to 400,000 lambs or 40% of total production to southern factories.

Controls

The reason that the legislation could frustrate this trade is that because while there are no tariff implications, if NI is outside of the EU single market, then goods leaving NI for the EU (Republic of Ireland) are likely to be subject to full sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) controls.

These are an EU requirement on all goods of animal and plant origin entering the EU from outside and are currently applied to all these goods entering continental markets from Britain.

They have also been a source of frustration on trade between Britain and Northern Ireland, one of the areas of the protocol that has caused operational difficulties.

However, in the bigger picture, it is the protocol that enables goods trade across the Irish border and, as the NI trade association for beef factories said, it gives its members “significant benefits relative to other UK and EU regions and our members are anxious that those benefits are protected”.

Worst nightmare for Irish farmers

For farmers south of the border, there are no plans by the UK to do anything in the legislation to impact on trade and they have deferred the introduction of full border controls on SPS goods entering the UK from the EU.

However, the risk is that this legislation is the first step on what could escalate to a full trade war between the EU and UK.

The ultimate end game is a collapse of the trade and co-operation agreement (TCA) between the EU and UK, which would mean the introduction of tariffs and, in practice, a no-deal Brexit.

It would mean that tariffs of up to £2.53/kg (€2.94/kg) plus 12% of value on a kilo of boneless beef

This is the nightmare scenario for Irish farmers. If the TCA collapses and we are facing full tariffs, it would mean that tariffs of up to £2.53/kg (€2.94/kg) plus 12% of value on a kilo of boneless beef or £1.39/kg (€1.62/kg) on cheddar.

These are Ireland’s largest agri-food exports to Britain and tariffs would make them prohibitively expensive, particularly as the UK has a trade deal with Australia and New Zealand that will remove all tariffs.

Scale of tariff burden

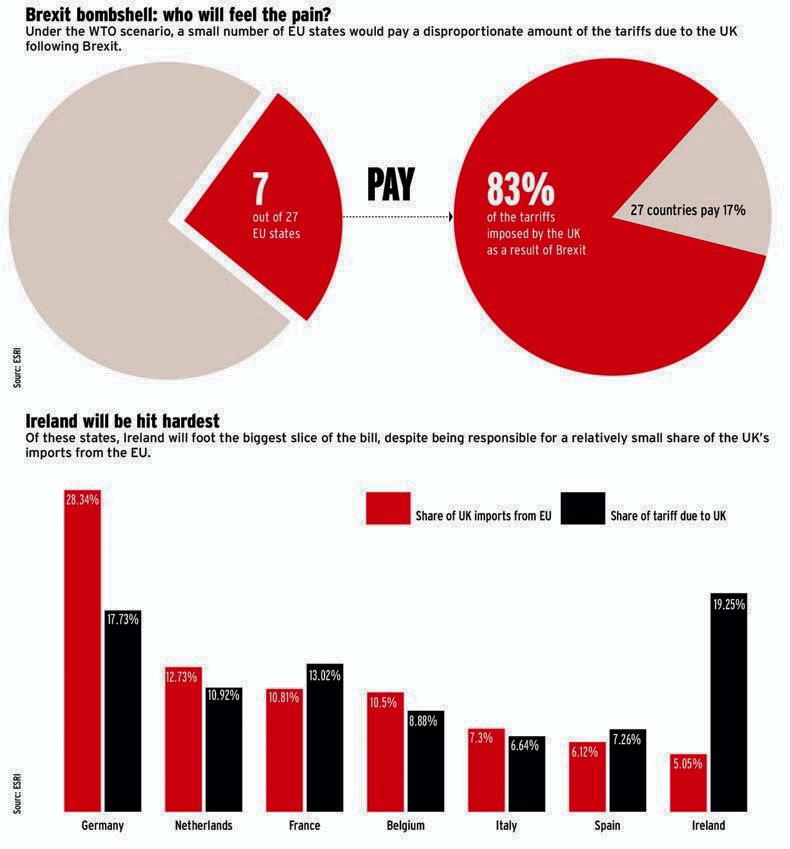

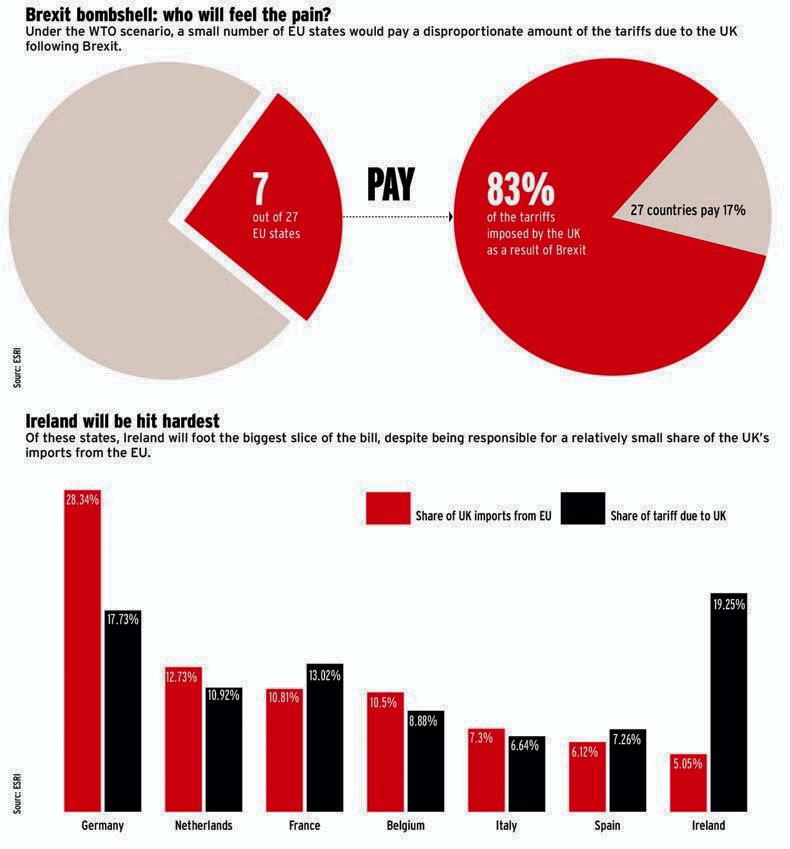

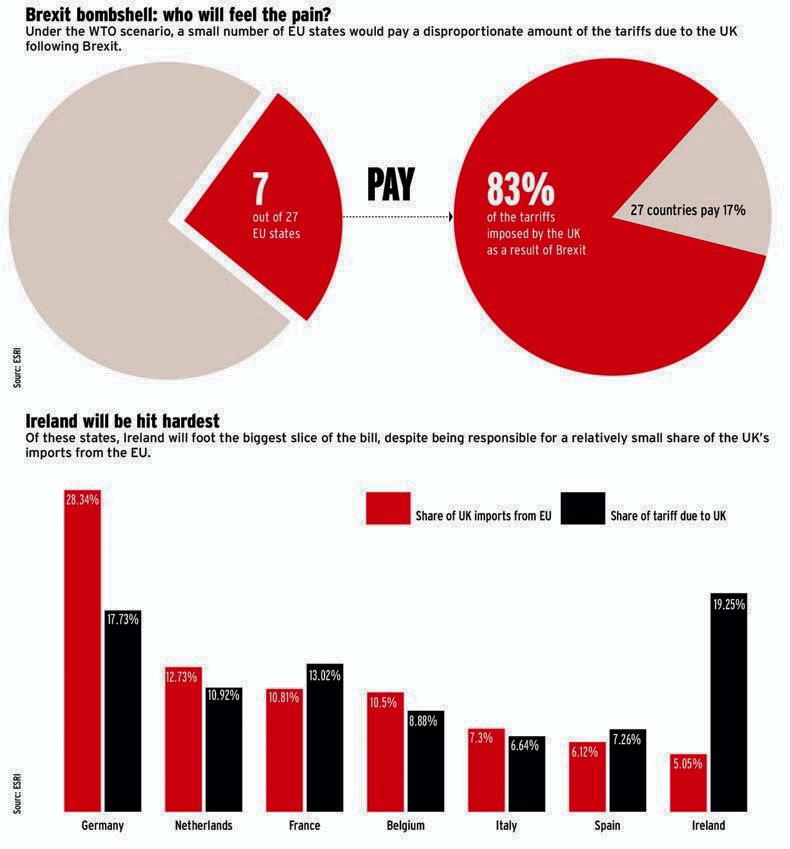

To put this in context, without the TCA, Irish exports to the UK, which account for just 5% of entire EU exports, would carry 19.5% of all EU tariffs on exports to the UK, the highest of any member state.

Figure 1: Ireland, with just 5% of EU trade with Britain, would carry the highest burden of tariffs if the EU-UK trade agreement were to collapse.

This is because tariffs on beef and dairy products are disproportionately high compared with other goods.

As Figure 1 illustrates, the disproportionate tariff burden is next illustrated by the fact that we are higher than Germany, which, despite having over 28% of all EU trade with the UK, would pay less tariffs than Ireland.

Absence of a TCA and a no-deal Brexit would mean tariffs in excess of €1bn annually and effectively close the UK market to Irish beef and cheddar exports.

Hope for the best, prepare for the worst

A no-deal Brexit was regularly talked about ahead of the UK leaving the EU single market and the TCA was a welcome last-minute relief.

Proposed UK legislation is not compatible with the protocol agreed to allow NI remain part of the EU single market.

The legislation will take up to a year to be fully passed and that may have political difficulties in Westminster.

It allows time for negotiation and common sense to prevail, which is what many expect ultimately to happen as there is a general understanding of how a solution could be based on goods for NI only and those likely to be traded onwards.

However, we need to understand that while it should happen, it is no guarantee that it will and Ireland should have the Brexit Adjustment Reserve (BAR) fund at the ready just in case.

The decision by the UK government to bring forward legislation to overrule the Northern Ireland (NI) protocol could effectively remove NI from the EU single market.

This, in turn, effectively closes cross-border markets to NI farmers.

Most exposed if this happened are dairy farmers, who have 800m litres or one-third of total NI production processed in dairies south of the border.

NI sheep farmers would also be hit, as they send up to 400,000 lambs or 40% of total production to southern factories.

Controls

The reason that the legislation could frustrate this trade is that because while there are no tariff implications, if NI is outside of the EU single market, then goods leaving NI for the EU (Republic of Ireland) are likely to be subject to full sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) controls.

These are an EU requirement on all goods of animal and plant origin entering the EU from outside and are currently applied to all these goods entering continental markets from Britain.

They have also been a source of frustration on trade between Britain and Northern Ireland, one of the areas of the protocol that has caused operational difficulties.

However, in the bigger picture, it is the protocol that enables goods trade across the Irish border and, as the NI trade association for beef factories said, it gives its members “significant benefits relative to other UK and EU regions and our members are anxious that those benefits are protected”.

Worst nightmare for Irish farmers

For farmers south of the border, there are no plans by the UK to do anything in the legislation to impact on trade and they have deferred the introduction of full border controls on SPS goods entering the UK from the EU.

However, the risk is that this legislation is the first step on what could escalate to a full trade war between the EU and UK.

The ultimate end game is a collapse of the trade and co-operation agreement (TCA) between the EU and UK, which would mean the introduction of tariffs and, in practice, a no-deal Brexit.

It would mean that tariffs of up to £2.53/kg (€2.94/kg) plus 12% of value on a kilo of boneless beef

This is the nightmare scenario for Irish farmers. If the TCA collapses and we are facing full tariffs, it would mean that tariffs of up to £2.53/kg (€2.94/kg) plus 12% of value on a kilo of boneless beef or £1.39/kg (€1.62/kg) on cheddar.

These are Ireland’s largest agri-food exports to Britain and tariffs would make them prohibitively expensive, particularly as the UK has a trade deal with Australia and New Zealand that will remove all tariffs.

Scale of tariff burden

To put this in context, without the TCA, Irish exports to the UK, which account for just 5% of entire EU exports, would carry 19.5% of all EU tariffs on exports to the UK, the highest of any member state.

Figure 1: Ireland, with just 5% of EU trade with Britain, would carry the highest burden of tariffs if the EU-UK trade agreement were to collapse.

This is because tariffs on beef and dairy products are disproportionately high compared with other goods.

As Figure 1 illustrates, the disproportionate tariff burden is next illustrated by the fact that we are higher than Germany, which, despite having over 28% of all EU trade with the UK, would pay less tariffs than Ireland.

Absence of a TCA and a no-deal Brexit would mean tariffs in excess of €1bn annually and effectively close the UK market to Irish beef and cheddar exports.

Hope for the best, prepare for the worst

A no-deal Brexit was regularly talked about ahead of the UK leaving the EU single market and the TCA was a welcome last-minute relief.

Proposed UK legislation is not compatible with the protocol agreed to allow NI remain part of the EU single market.

The legislation will take up to a year to be fully passed and that may have political difficulties in Westminster.

It allows time for negotiation and common sense to prevail, which is what many expect ultimately to happen as there is a general understanding of how a solution could be based on goods for NI only and those likely to be traded onwards.

However, we need to understand that while it should happen, it is no guarantee that it will and Ireland should have the Brexit Adjustment Reserve (BAR) fund at the ready just in case.

SHARING OPTIONS