What is bluetongue?

Bluetongue is a virus that affects cattle, sheep and other ruminants, primarily spreading by the bite of the midge.

The midge is typically active between April and November in Ireland, but milder conditions can prolong this activity.

At least eight of Ireland’s 16 most common midge can spread the disease, the Department of Agriculture has said.

The virus does not affect humans and cannot be transmitted through milk or meat.

The Department of Agriculture stated that the mortality rates can be as high as 70% and sheep are known to exhibit clearer symptoms than cattle.

Some flocks or herds infected with the virus may only see one or two animals showing visible symptoms and even these cases may not be easily visible, according to the Department.

What are the symptoms of bluetongue in cattle?

The Department of Agriculture has listed a wide range of symptoms for the disease and although some animals may not show these signs, they can spread the disease further.

A cow showing facial swelling that is a symptom of the bluetongue virus.

The symptoms in cattle include fever, loss of appetite, tiredness, reduced milk yields, discharge from the nose or eyes, reddening or cracking of the tissue around the udder and swelling in the mouth or face.

What are the symptoms of bluetongue in sheep?

Sheep typically exhibit stronger symptoms than cattle do.

These include a fever, swelling of the head and neck, lameness, drooling, a discolouration and swelling of the tongue and death.

How could bluetongue come to Ireland?

There are three main routes through which bluetongue could enter the country:

The import of infected animals.The import of infected animal materials, such as blood, semen or embryos.Midge being carried to Ireland with infected midges carried by wind.The Department has said that importing infected animals represents the “greatest threat” to Ireland remaining bluetongue-free.

The disease can be easier to spot in sheep than it is in cattle. \ Donal O'Leary

Advice has been issued to those planning on importing livestock from infected areas and the European continent more generally.

This includes asking whether there is a need to source animals from outside the country, only importing between December and March if importing is necessary and only importing livestock which are not pregnant.

What should I do if I have imported livestock?

The Department recommends that farmers should double-check that any livestock’s identification documents and health certs are in order if they have been imported.

The stock should be provided with access to clean water, bedding and feed in housing that is isolated from the rest of the flock or herd.

Farmers have been told to check the general condition of the animals and contact their vet immediately if animals appear unwell.

The local regional veterinary office (RVO) should be contacted as soon as the imported animals arrive on-farm to arrange a post-import visit.

What would happen if bluetongue was detected in Ireland?

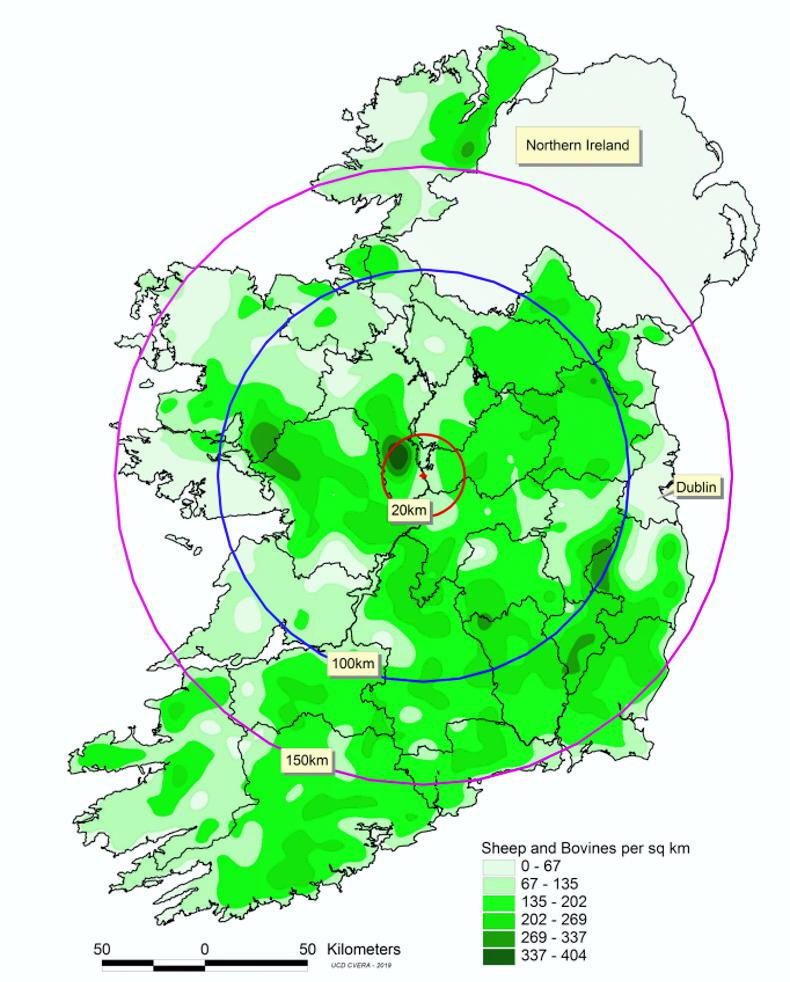

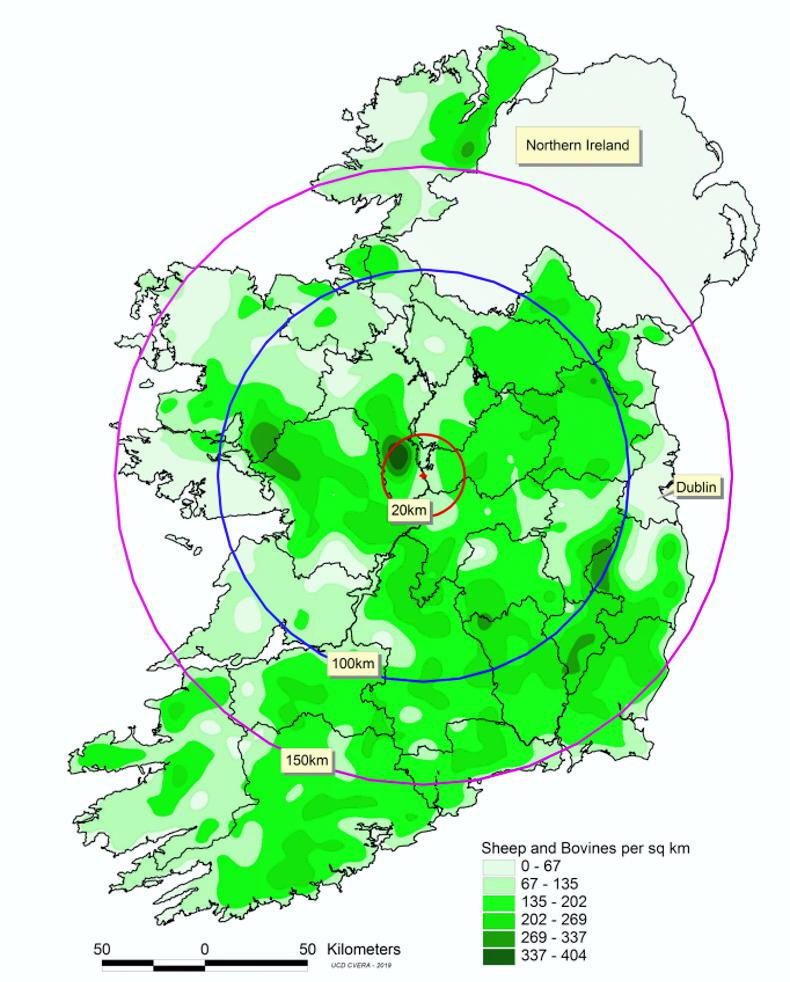

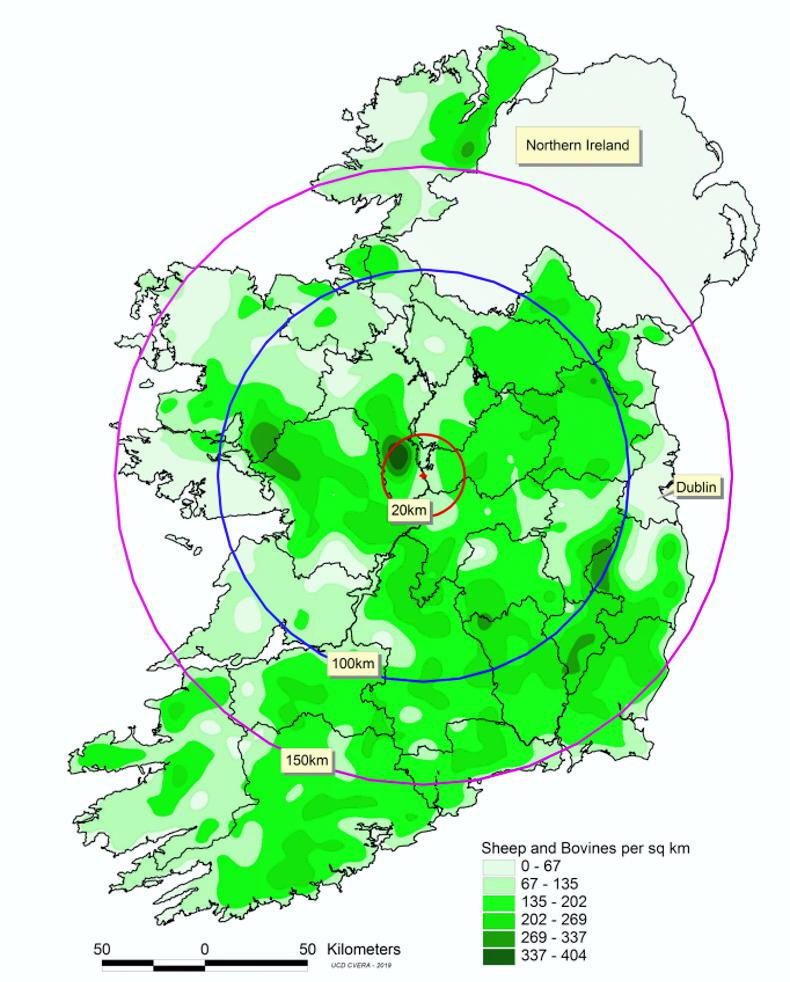

A control zone of 20km in radius, a protection zone of 100km in radius and a surveillance zone of 150km in radius would be established around the farm on which the virus was detected, the Department said.

Livestock movements would be restricted in these zones and infected animals may need to be slaughtered to control the spread of the virus.

Example of a restriction map with distances marked.

There may be orders to house livestock when the vector is active, which can be between April and November in Ireland.

Eradication efforts may target the midge by destroying its habitats and by using insecticides.

Is there a vaccine?

Vaccination may be used to stem the spread of the disease, depending on the strain.

However, the strain found in England last week and on the continent in recent months is BTV3, for which there is no vaccine currently on the market in the EU.

There is no vaccine currently available for the BTV3 strain on EU markets. / Philip Doyle

What could a bluetongue case mean for trade?

The trade implications of a bluetongue case would depend on the country of destination for any animals, semen or embryos planned for export out of the country.

If it is intended to export to a country which is currently bluetongue-free, there will be strict conditions around exporting animals, semen and embryos.

If the country has detected bluetongue, movement of animals, semen and embryos will be under similar conditions to the restriction zones within Ireland.

Livestock and vehicles exporting livestock would need to be treated with insecticides.

A case of bluetongue would see animal movements restricted. \ Philip Doyle

The Department has stated that as the disease is not transmitted in meat and milk, there should not be similar restrictions applied to these products.

What should I do if I think I have found a case of bluetongue?

Farmers who suspect a case of bluetongue virus in their herd or flock should contact local RVO.

If a case is suspected, the animal in no cattle or sheep are to be moved from the farm holding until blood samples have returned negative results.

Where has bluetongue been detected in Europe?

The first case of bluetongue in the disease’s current to be detected in the UK was found in Kent, England, last week.

Outbreaks were reported in the Netherlands and France from September, while Belgium and Germany saw their first cases in years in October.

What is bluetongue?

Bluetongue is a virus that affects cattle, sheep and other ruminants, primarily spreading by the bite of the midge.

The midge is typically active between April and November in Ireland, but milder conditions can prolong this activity.

At least eight of Ireland’s 16 most common midge can spread the disease, the Department of Agriculture has said.

The virus does not affect humans and cannot be transmitted through milk or meat.

The Department of Agriculture stated that the mortality rates can be as high as 70% and sheep are known to exhibit clearer symptoms than cattle.

Some flocks or herds infected with the virus may only see one or two animals showing visible symptoms and even these cases may not be easily visible, according to the Department.

What are the symptoms of bluetongue in cattle?

The Department of Agriculture has listed a wide range of symptoms for the disease and although some animals may not show these signs, they can spread the disease further.

A cow showing facial swelling that is a symptom of the bluetongue virus.

The symptoms in cattle include fever, loss of appetite, tiredness, reduced milk yields, discharge from the nose or eyes, reddening or cracking of the tissue around the udder and swelling in the mouth or face.

What are the symptoms of bluetongue in sheep?

Sheep typically exhibit stronger symptoms than cattle do.

These include a fever, swelling of the head and neck, lameness, drooling, a discolouration and swelling of the tongue and death.

How could bluetongue come to Ireland?

There are three main routes through which bluetongue could enter the country:

The import of infected animals.The import of infected animal materials, such as blood, semen or embryos.Midge being carried to Ireland with infected midges carried by wind.The Department has said that importing infected animals represents the “greatest threat” to Ireland remaining bluetongue-free.

The disease can be easier to spot in sheep than it is in cattle. \ Donal O'Leary

Advice has been issued to those planning on importing livestock from infected areas and the European continent more generally.

This includes asking whether there is a need to source animals from outside the country, only importing between December and March if importing is necessary and only importing livestock which are not pregnant.

What should I do if I have imported livestock?

The Department recommends that farmers should double-check that any livestock’s identification documents and health certs are in order if they have been imported.

The stock should be provided with access to clean water, bedding and feed in housing that is isolated from the rest of the flock or herd.

Farmers have been told to check the general condition of the animals and contact their vet immediately if animals appear unwell.

The local regional veterinary office (RVO) should be contacted as soon as the imported animals arrive on-farm to arrange a post-import visit.

What would happen if bluetongue was detected in Ireland?

A control zone of 20km in radius, a protection zone of 100km in radius and a surveillance zone of 150km in radius would be established around the farm on which the virus was detected, the Department said.

Livestock movements would be restricted in these zones and infected animals may need to be slaughtered to control the spread of the virus.

Example of a restriction map with distances marked.

There may be orders to house livestock when the vector is active, which can be between April and November in Ireland.

Eradication efforts may target the midge by destroying its habitats and by using insecticides.

Is there a vaccine?

Vaccination may be used to stem the spread of the disease, depending on the strain.

However, the strain found in England last week and on the continent in recent months is BTV3, for which there is no vaccine currently on the market in the EU.

There is no vaccine currently available for the BTV3 strain on EU markets. / Philip Doyle

What could a bluetongue case mean for trade?

The trade implications of a bluetongue case would depend on the country of destination for any animals, semen or embryos planned for export out of the country.

If it is intended to export to a country which is currently bluetongue-free, there will be strict conditions around exporting animals, semen and embryos.

If the country has detected bluetongue, movement of animals, semen and embryos will be under similar conditions to the restriction zones within Ireland.

Livestock and vehicles exporting livestock would need to be treated with insecticides.

A case of bluetongue would see animal movements restricted. \ Philip Doyle

The Department has stated that as the disease is not transmitted in meat and milk, there should not be similar restrictions applied to these products.

What should I do if I think I have found a case of bluetongue?

Farmers who suspect a case of bluetongue virus in their herd or flock should contact local RVO.

If a case is suspected, the animal in no cattle or sheep are to be moved from the farm holding until blood samples have returned negative results.

Where has bluetongue been detected in Europe?

The first case of bluetongue in the disease’s current to be detected in the UK was found in Kent, England, last week.

Outbreaks were reported in the Netherlands and France from September, while Belgium and Germany saw their first cases in years in October.

SHARING OPTIONS