News that the European Commission has agreed to grant Ireland an extension to the existing nitrates derogation was announced in the Dáil chamber by Minister for Agriculture Martin Heydon on Thursday.

On the face of it, the announcement prevents a cliff-hanger cut to stocking rates next January and gives certainty to farmers, at least up to the end of 2028.

This will be welcomed by all farmers along with the dairy and beef industry.

When I spoke with the Minister and the European Commissioner for Environment Jessika Roswall in Dublin on 7 November, the key words repeated over and over again was that any deal must give “certainty for farmers” and be “legally robust”.

This decision to grant an extension to the existing derogation is a bit of a fudge. It gives certainty to farmers for three years, but then what?

In terms of being legally robust, the extension will grant the Department of Agriculture time to conduct appropriate assessments on Ireland’s 583 sub-catchments.

The objective is to avoid a legal challenge to the granting of the derogation if the Habitats Directive was not taken into account when granting said derogation.

Let’s be clear, this is not good news.

Under the Habitats Directive any plan or project likely to have a significant effect on a designated site or species must be subject to appropriate assessment of its implications for the site.

The legislation in the Habitats Directive states that there can be no deterioration to Special Area of Conservation (SAC) from a “project”.

The Dutch nitrates case ruled that a farm keeping livestock or applying fertilisers can be deemed a project.

There is now a mammoth task facing the Department to complete these 583 appropriate assessments within three years.

Some of these sub-catchments will be ruled out of scope of the assessment process as they don’t contain any derogation farms.

The assessments will have to conclude on whether or not a derogation farm, with its higher stocking rate, poses a risk to the protected biology within the SAC.

Of course, other farms that are not in derogation could have far higher nutrient losses than a derogation farmer, but depending on the scope of the assessments, this may not be considered

Take the freshwater pearl mussel as an example of a species protected by SAC designation in 19 locations.

According to the National Parks and Wildlife Service, increased nutrient load is one of the challenges faced by the pearl mussel.

Without pre-empting the outcome of the appropriate assessments, it could be difficult to prove that farms with higher stocking rates (derogation farms) in the sub-catchments within the SAC will not lead to increased nutrient load in these rivers.

For context, the following are some of the rivers that are in an SAC for freshwater pearl mussel;

Slaney River Valley SAC.Lower River Suir SAC.Newport River SAC.River Barrow and River Nore SAC.Lower River Shannon SAC.Blackwater River (Cork/Waterford) SAC.Bandon River SAC.Blackwater River (Kerry) SAC.A significant number of farms within these river catchments are in a nitrates derogation.

Of course, other farms that are not in derogation could have far higher nutrient losses than a derogation farmer, but depending on the scope of the assessments, this may not be considered.

None of this is black and white and there is growing recognition across Europe that the terminology in the Habitats Directive is being used as a weapon by environmental NGO’s to block industrial and farm development.

The only good news is that Ireland has been granted time to deal with the issues. However, while three years might seem like a long time, it will go by quickly.

It could take the Department of Agriculture most of that time to recruit the required number of ecologists to carry out the appropriate assessments, let alone complete them.

How much is this going to cost and who will pay for it? What future funding will be cut to say Teagasc or other sectors within the Department of Agriculture or what scheme payments will be cut to help pay for these assessments?

Other questions include what additional conditionality will be placed on farmers during the extension period?

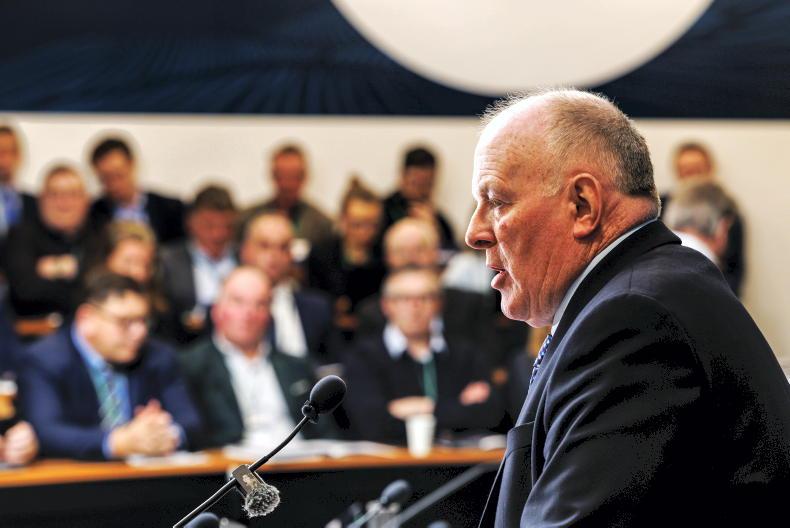

To be fair to Minister Heydon, there wasn’t much sense of triumphalism in his announcement of the extension.

Ireland sought a renewal of the derogation for the four-year term. It got a three-year extension while it starts to grasp the appropriate assessment nettle.

Whether or not this is just a stay of execution will remain to be seen. However, it does buy Ireland more time to prove that water quality is improving.

That might strengthen our case, but it’s now quite clear that granting a derogation is not about water quality, it’s about lawyers arguing over legal interpretation, precedent and case law.

The decision has yet to be ratified by the member states at the 9 December meeting of the nitrates committee. The terms and conditions will be better understood then.

Let's hope this is not a "slow no" to Ireland keeping the derogation long term.

News that the European Commission has agreed to grant Ireland an extension to the existing nitrates derogation was announced in the Dáil chamber by Minister for Agriculture Martin Heydon on Thursday.

On the face of it, the announcement prevents a cliff-hanger cut to stocking rates next January and gives certainty to farmers, at least up to the end of 2028.

This will be welcomed by all farmers along with the dairy and beef industry.

When I spoke with the Minister and the European Commissioner for Environment Jessika Roswall in Dublin on 7 November, the key words repeated over and over again was that any deal must give “certainty for farmers” and be “legally robust”.

This decision to grant an extension to the existing derogation is a bit of a fudge. It gives certainty to farmers for three years, but then what?

In terms of being legally robust, the extension will grant the Department of Agriculture time to conduct appropriate assessments on Ireland’s 583 sub-catchments.

The objective is to avoid a legal challenge to the granting of the derogation if the Habitats Directive was not taken into account when granting said derogation.

Let’s be clear, this is not good news.

Under the Habitats Directive any plan or project likely to have a significant effect on a designated site or species must be subject to appropriate assessment of its implications for the site.

The legislation in the Habitats Directive states that there can be no deterioration to Special Area of Conservation (SAC) from a “project”.

The Dutch nitrates case ruled that a farm keeping livestock or applying fertilisers can be deemed a project.

There is now a mammoth task facing the Department to complete these 583 appropriate assessments within three years.

Some of these sub-catchments will be ruled out of scope of the assessment process as they don’t contain any derogation farms.

The assessments will have to conclude on whether or not a derogation farm, with its higher stocking rate, poses a risk to the protected biology within the SAC.

Of course, other farms that are not in derogation could have far higher nutrient losses than a derogation farmer, but depending on the scope of the assessments, this may not be considered

Take the freshwater pearl mussel as an example of a species protected by SAC designation in 19 locations.

According to the National Parks and Wildlife Service, increased nutrient load is one of the challenges faced by the pearl mussel.

Without pre-empting the outcome of the appropriate assessments, it could be difficult to prove that farms with higher stocking rates (derogation farms) in the sub-catchments within the SAC will not lead to increased nutrient load in these rivers.

For context, the following are some of the rivers that are in an SAC for freshwater pearl mussel;

Slaney River Valley SAC.Lower River Suir SAC.Newport River SAC.River Barrow and River Nore SAC.Lower River Shannon SAC.Blackwater River (Cork/Waterford) SAC.Bandon River SAC.Blackwater River (Kerry) SAC.A significant number of farms within these river catchments are in a nitrates derogation.

Of course, other farms that are not in derogation could have far higher nutrient losses than a derogation farmer, but depending on the scope of the assessments, this may not be considered.

None of this is black and white and there is growing recognition across Europe that the terminology in the Habitats Directive is being used as a weapon by environmental NGO’s to block industrial and farm development.

The only good news is that Ireland has been granted time to deal with the issues. However, while three years might seem like a long time, it will go by quickly.

It could take the Department of Agriculture most of that time to recruit the required number of ecologists to carry out the appropriate assessments, let alone complete them.

How much is this going to cost and who will pay for it? What future funding will be cut to say Teagasc or other sectors within the Department of Agriculture or what scheme payments will be cut to help pay for these assessments?

Other questions include what additional conditionality will be placed on farmers during the extension period?

To be fair to Minister Heydon, there wasn’t much sense of triumphalism in his announcement of the extension.

Ireland sought a renewal of the derogation for the four-year term. It got a three-year extension while it starts to grasp the appropriate assessment nettle.

Whether or not this is just a stay of execution will remain to be seen. However, it does buy Ireland more time to prove that water quality is improving.

That might strengthen our case, but it’s now quite clear that granting a derogation is not about water quality, it’s about lawyers arguing over legal interpretation, precedent and case law.

The decision has yet to be ratified by the member states at the 9 December meeting of the nitrates committee. The terms and conditions will be better understood then.

Let's hope this is not a "slow no" to Ireland keeping the derogation long term.

SHARING OPTIONS