The focus of the dairy industry since the ending of quotas has been on expansion. Farmers have expanded through additional cows and land, while processors have invested in new stainless steel to handle it.

However, with all this expansion and building, there has been a slow change happening in the background that will have far larger consequences on how the milk price is determined in the future. Currently, Ireland exports 85% of its dairy output and this will rise to 90% in the future.

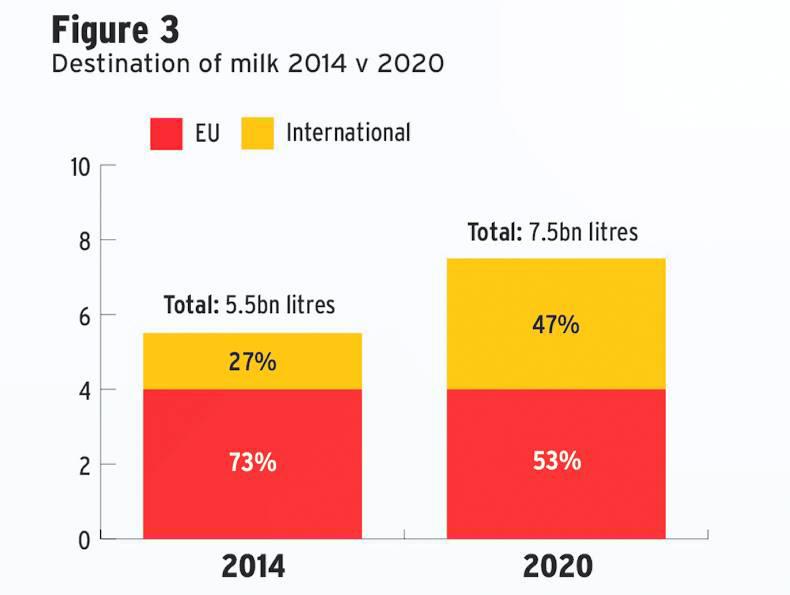

With stagnant demand in Europe and with EU production up 2% last year, the extra 2.5bn litres from Ireland will be destined for international markets. As shown in Figure 3, 27% of our dairy exports currently go to international markets and in the future this will grow to 47%, dominated by powder rather than butter or cheese.

Where is the milk going today?

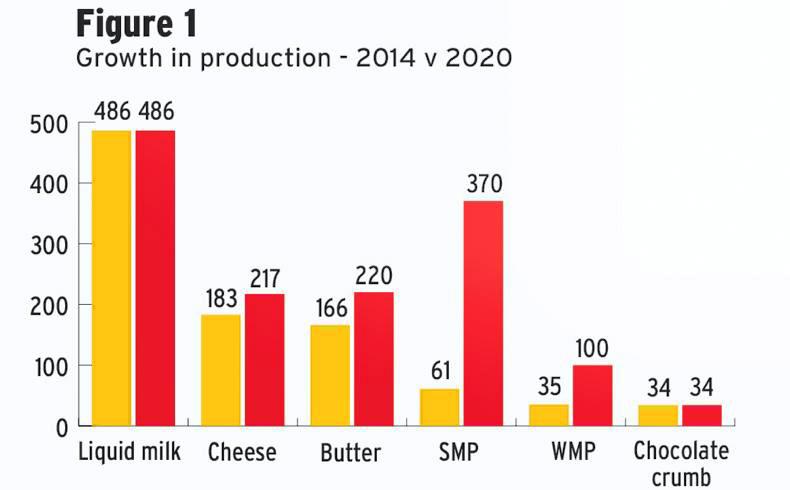

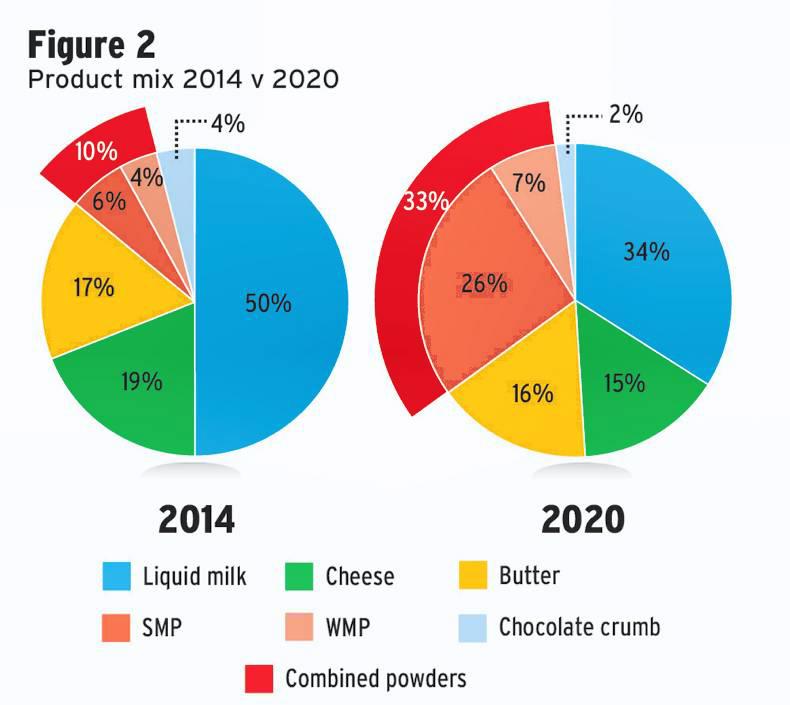

Figure 2 shows that in 2014, 50% of Ireland’s total dairy output volume went to the liquid milk market, predominately an internal market. It is important to note that this is not milk utilisation as liquid milk accounts for about 8% of the milk pool. It also takes more milk to make a tonne of butter, cheese or powder. For example it takes 7 ½ litres of milk to make a kg of WMP. But taking the tonnes of output, liquid milk makes up the largest proportion. As consumers’ habits have changed, like all developed countries the liquid milk market has remained static and is not expected to grow beyond its current 486,000t in the future. As we grow output from 5bn litres to 7.5bn litres, liquid milk will become much less important, and will account for a much smaller slice (33%) of Ireland’s total dairy output by 2020.

Cheese, which is currently our second-largest dairy product, made up 19% of dairy output in 2014. While output will grow a further 19% to 217,000t by 2020, its share of total dairy output will reduce to 15%.

Butter, another staple outlet for Irish milk, will overtake cheese in volume terms with production expected to grow 33% by 2020 to 220,000t. This is predominantly due to the resurgence in demand for butter in the US. Irish butter accounts for 50% of all EU butter exports to the US, thanks to the Kerrygold brand. Currently butter accounts for 17% of total dairy output, and it will maintain this share in 2020.

Traditional markets for Irish cheese and butter have been to European markets. Our largest market for both is the UK, followed by Germany and France. The US has become an important player, also becoming our fifth-largest market for both.

These three traditional products currently account for 90% of total dairy output (including chocolate crumb). While liquid milk is consumed domestically it has been the international price of cheese and butter that has largely determined the Irish milk price up to now.

However, by 2020, while volumes will have grown for cheese and butter, they will have become much less important to the overall dairy product mix in Ireland. In fact, they will then account for less than two-thirds (65%).

Powders to dominate

The majority of our increased milk production will be dried into powders.

SMP production will expand fivefold from its current 61,000t to reach 370,000t, making it almost twice as important as cheese in the mix.

Meanwhile, WMP production will increase threefold from its current 35,000t to reach 100,000t in 2020. Combined, powders will go from 10% of the product mix today to 33% by 2020, placing us firmly on the global commodity powder markets competing directly with NZ and its milk pool four times ours.

Investment in drying

The majority of investment over the past number of years has gone into new or upgraded existing dryers to process this milk. Glanbia, Dairygold, Lakeland, Aurivo, North Cork, Carbery, Arrabawn and LacPatrick have all expanded drying capacity.

Our seasonal production system has in some way pushed us down this route. While it is one thing to build an industry to facilitate a low-cost grass-based seasonal system, it does have implications beyond the farm gate.

Simply put, the majority of the extra milk that is produced in Ireland will end up in international powder markets, putting us on a different playing field than we have become accustomed to.

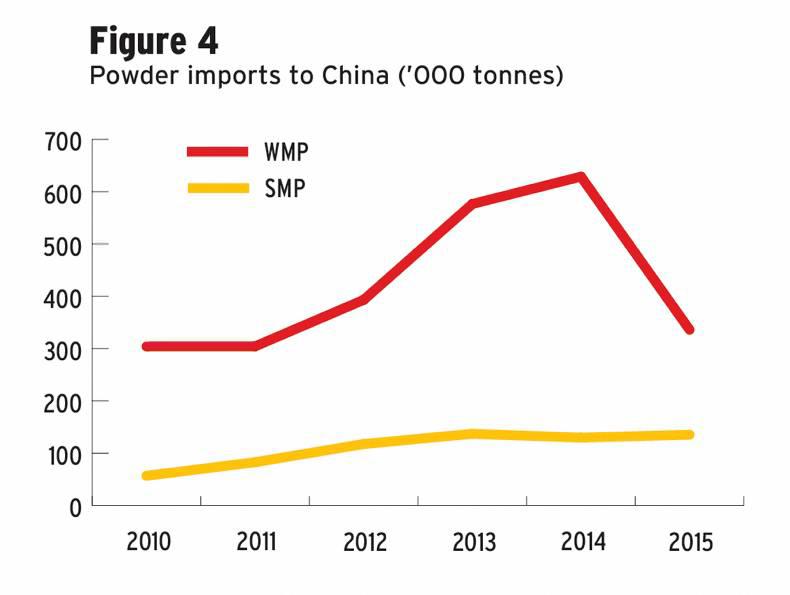

With a greater proportion of our product mix in powder, farmer milk prices will be more exposed than ever to the swings of international markets. The benchmark price reference for milk powders is the bi-weekly Global Dairy Trade (GDT) auction in New Zealand. WMP is the key commodity traded on the GDT, making up over half of sales and the main driver of the index’s performance. New Zealand also accounts for 50% of all WMP traded in the world and 22% of SMP.

Already, 60% of powders produced in Ireland end up in markets outside the EU. While powders only represent a small part of the current mix, in the future global trade benchmarks, such as the GDT, will become more of a proxy for the Irish milk price.

While it would have been more efficient and cheaper for the dairy processing sector to force a flat production curve, unlike the beef sector, it has developed a processing industry that puts the farmer’s production system first. This is a model that has proven hugely successful to the brand and image of Irish dairy produce abroad.

But with one third of Ireland’s dairy output destined for international powder markets in the future, there is no doubt that the Irish dairy sector overall is a commodity player on international markets. As such, only the most efficient farmers will survive the lows of global volatility.

Irish processors and Ornua are playing a part in moving a proportion of our product into value added markets from branded Kerrygold butter, specialised infant formula and customised dairy ingredients. This will help insulate against volatility but these products will only ever account for a small proportion of total dairy output.

If we look at the last two years, market volatility can come from anywhere. Chinese demand was the greatest driver of global dairy prices up to two years ago. After overstocking, it is now working through this. The Russian embargo disrupted the global trade flow. Low grain prices fuelled milk production in the US. Most recently we see how the collapse in the oil price has impacted on the buying power of oil dependent economies such as Nigeria and Algeria.

Ireland has now one of the most invested dairy processing industries in Europe. The next phase will be to develop risk management tools that protect the farmer and therefore the processor from volatility and security of supply. After all, a low-cost production system can only go so far.

SHARING OPTIONS