A few dry weeks in April and May and we can quickly forget that high rainfall levels tend to be the scourge of tillage farmers in this country. Weather and tillage is not just about disease – it also has a huge affect on mechanisation requirement and, therefore, significantly affects production costs.

I have been involved in farming at Kilmore, near Tallow in Co Waterford, for over 50 years. My wife Sheila and I farm in partnership. We grow crops such as winter barley, winter oats, winter wheat and spring barley. In total, our farm business is based on 220 acres (89ha).

The nature of our farming enterprise and all tillage farming is very weather-dependant. Rainfall is by far the most important single weather factor. It affects crops from establishment through to harvest, as well as affecting disease pressure and all management operations. Rainfall amounts and occurrences affect the most basic decisions concerning field work and how this affects crop production. Recording rainfall can provide invaluable assistance in helping make decisions concerning our farming operations.

For this reason, I applied to Met Eireann to become a voluntary Met observer in April 1986 and I have been recording rainfall here in Kilmore since then. I recently completed a project on Microsoft Excel and I used much of the data collected over almost three decades to ask some basic questions of weather events relating to rainfall during this period. The results are interesting and reflect the great challenges associated with crop production in this area.

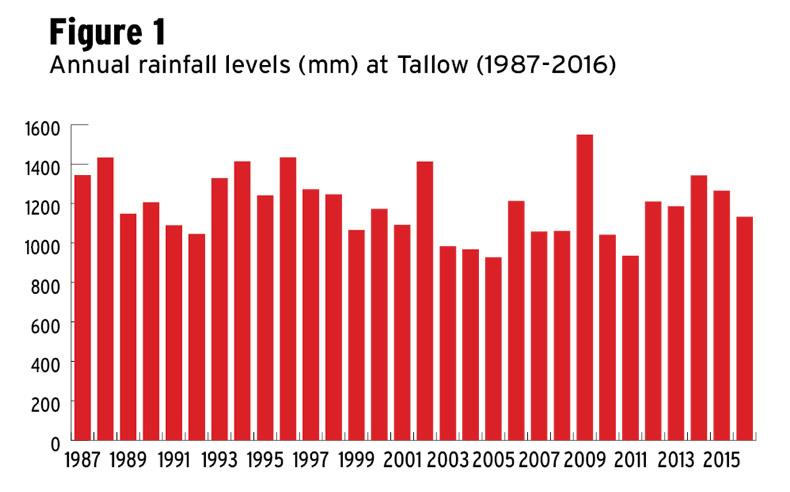

Over the past 30 years, our annual rainfall amounts have varied from 1,549.8mm (61in) in the wettest year of 2009 to 926.8mm (36.49in) in 2005. Our driest years might still be considered as wet in other parts of the country.

Across these 30 years our average annual rainfall (calendar year) works out at 1,194.24mm (47in). This is a definite hindrance to efficient crop production. The range in annual rainfall is shown in Figure 1. This shows that 15 of the past 30 years were above the average of 40in per year and reinforces the challenge of crop management.

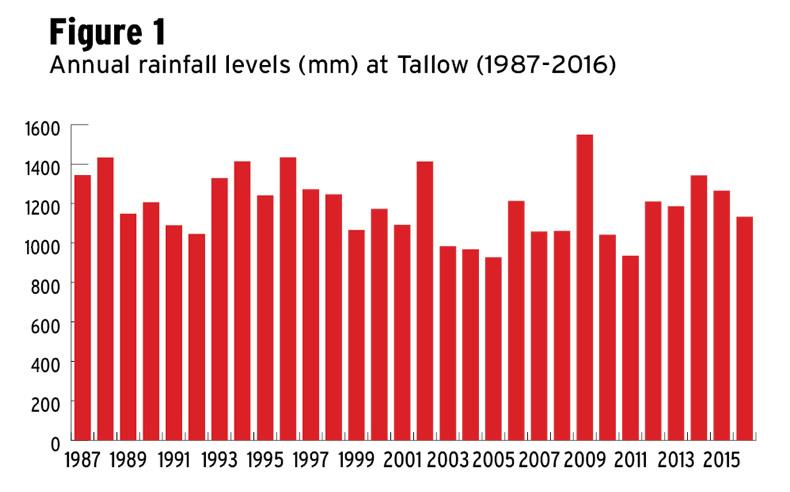

But average annual data does not tell the full story. Figure 2 shows the number of days in each of the 30 years that were either dry (less than 1mm of rainfall), had more than 1mm of rain, more than 12.5mm or more than 25mm.

With an average of over 150 days with more than 1mm of rain, one can quickly identify the challenge of having crops sufficiently dry for spraying. And this was as high as 183 days in 1994. We still had an average of 119 days with no, or virtually no, rain and we must hope that these dry days coincide as much as possible with the times when work needs to be done.

I have come to accept that a wet year is one with 1,270mm (50in) or greater. In the same way, we would categorise a year with 1,016mm (40in), or less, as a dry year. Lack of rainfall is seldom a real issue in this part of the country.

John O’Mahony can be contacted at omahonyjs3@gmail.com or on 087-256 6987.

SHARING OPTIONS