Is there still a need to

report suspect cases?

While disease caused by the Schmallenberg virus (SBV) is not classified as a notifiable disease, the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine (DAFM) wishes to be kept informed of the prevalence of the disease and how it is affecting livestock in Ireland. To date, the disease has been confined to the south and south-east of the country, but it is anticipated to move north-west over time. Therefore, while there is no obligation to report new cases to the Department, we would ask farmers to submit suspected cases through their veterinary practitioner, for post mortem examination at their nearest Regional Veterinary Laboratory (RVL).

Is there a difference in the losses experienced between cattle and sheep?

The loss per case is likely to be greater among cattle rather than sheep due to the relative value of cows and calves versus ewes and lambs. However, due to the more compact nature of the sheep breeding season there is likely to be more cases of SBV in an affected sheep flock versus an affected cattle herd. Therefore, there is the potential for SBV to have a greater relative economic impact on sheep flocks than cattle herds.

Is Schmallenberg travelling across the country as expected this year?

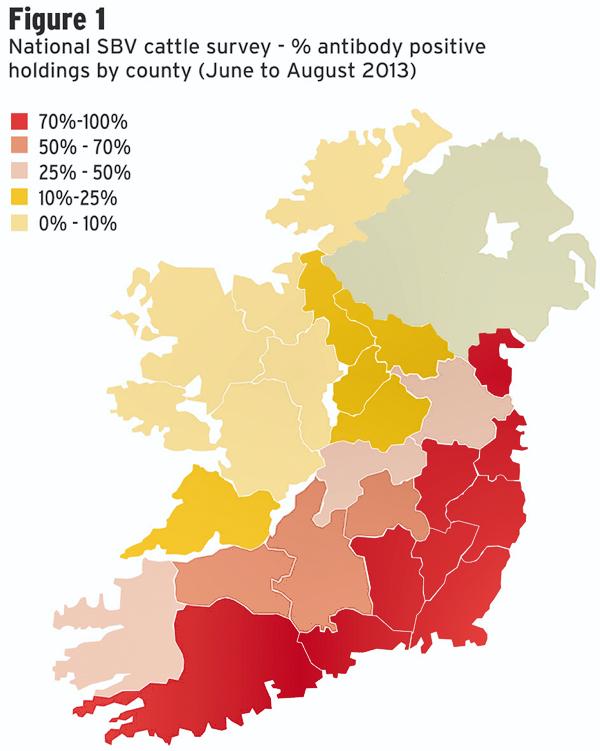

DAFM has carried out surveys for SBV antibodies in cattle and sheep in 2013. See figure 1. Studies in cattle and sheep indicate that the disease has, more or less, remained in the areas in which it was identified earlier in the year. So far it has not spread to new areas. This is somewhat surprising, but similar findings have been reported before in Europe in midge borne diseases, where the extent and speed of spread may vary from year to year.

How is the virus spread?

The infection is spread by the bite of infected midges. The female needs a blood meal for her eggs to mature so that they can be laid. Midges are most active from April to December.

What are the losses experienced in affected flocks and herds due to Schmallenberg virus infection?

In sheep, cattle and goats, SBV causes abortions, stillbirths and congenital deformities. Many of the deformities involve the fusion of joints, resulting in conditions such as twisted necks (torticollis), fused limb joints (arthrogryposis) and curved back (kyphosis). The lower jaw may also be abnormally short (undershot).

The brain of affected neonates may be grossly underdeveloped, resulting in clinical signs of a nervous nature – uncoordination, trembling, partial paralysis. In cattle SBV is also known to cause fever, milk drop, inappetence and diarrhoea in adult cattle at the time of infection (acute phase of disease immediately after infection by midge bite).

What is the highest risk period for cattle and sheep to contract the virus that will result in the greatest losses?

The greatest losses are associated with the development of deformed foetuses. The period of susceptibility in sheep is between day 28 and day 56 of pregnancy and between day 62 and day 170 of pregnancy in cattle. If ewes and cows at these stages of pregnancy are exposed to SBV-infected midges for the first time, they are at the greatest risk of producing a deformed foetus.

Immunologically naive, early lambing flocks which were synchronised appear to be the most severely affected flocks. The later lambing parts of such flocks tended to have fewer, if any, congenital abnormalities related to the virus.

Can animals become naturally immune to the virus?

Animals which have had a natural infection develop acquired resistance to the infection. Based on our current knowledge, we assume such animals are considered protected against further infection. However, this is a new virus to science and some questions cannot be answered, such as whether this immunity is life-long.

Are there any long-term health or production problems with animals which were infected with Schmallenberg virus?

Obviously deformed lambs and calves have no long-term future, even if they survive. However, once their dams recover from giving birth to them, and don’t develop any infections, there will be no long-term implications.

Is there a human health risk with this virus?

This condition is confined to ruminants and does not affect people.

What is the current situation in other countries in relation to Schmallenberg virus?

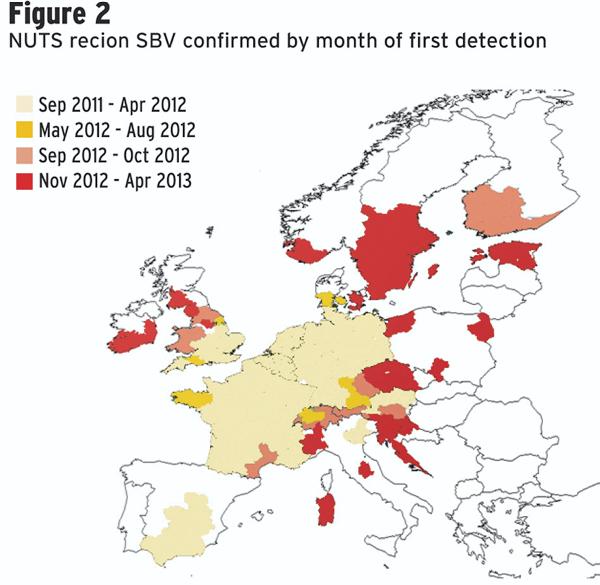

Disease due to SBV was first identified in the town of Schmallenberg in Germany in the autumn of 2011. Since then it has spread across Europe. Details of when it was first diagnosed in each country is shown in figure 2.

If my flock or herd was exposed to the virus last year what is likely to happen in this coming calving and lambing season?

SBV was first diagnosed in Ireland just over 12 months ago, having been first identified and diagnosed in Germany the previous year.

Therefore, our understanding of how the disease behaves is evolving. However, Akabane, a related virus that affects ruminants in Australia, provides us with clues as to how SBV may behave in Ireland.

Animals which have been exposed to the virus prior to pregnancy will develop an immunity and the disease is not likely to be seen in such animals.

In herds/flocks in endemically infected areas, any new infections are likely to be confined to younger animals (heifers and hoggets) and animals introduced to the herd from non-infected regions.

Q&A continued here

Is there still a need to

report suspect cases?

While disease caused by the Schmallenberg virus (SBV) is not classified as a notifiable disease, the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine (DAFM) wishes to be kept informed of the prevalence of the disease and how it is affecting livestock in Ireland. To date, the disease has been confined to the south and south-east of the country, but it is anticipated to move north-west over time. Therefore, while there is no obligation to report new cases to the Department, we would ask farmers to submit suspected cases through their veterinary practitioner, for post mortem examination at their nearest Regional Veterinary Laboratory (RVL).

Is there a difference in the losses experienced between cattle and sheep?

The loss per case is likely to be greater among cattle rather than sheep due to the relative value of cows and calves versus ewes and lambs. However, due to the more compact nature of the sheep breeding season there is likely to be more cases of SBV in an affected sheep flock versus an affected cattle herd. Therefore, there is the potential for SBV to have a greater relative economic impact on sheep flocks than cattle herds.

Is Schmallenberg travelling across the country as expected this year?

DAFM has carried out surveys for SBV antibodies in cattle and sheep in 2013. See figure 1. Studies in cattle and sheep indicate that the disease has, more or less, remained in the areas in which it was identified earlier in the year. So far it has not spread to new areas. This is somewhat surprising, but similar findings have been reported before in Europe in midge borne diseases, where the extent and speed of spread may vary from year to year.

How is the virus spread?

The infection is spread by the bite of infected midges. The female needs a blood meal for her eggs to mature so that they can be laid. Midges are most active from April to December.

What are the losses experienced in affected flocks and herds due to Schmallenberg virus infection?

In sheep, cattle and goats, SBV causes abortions, stillbirths and congenital deformities. Many of the deformities involve the fusion of joints, resulting in conditions such as twisted necks (torticollis), fused limb joints (arthrogryposis) and curved back (kyphosis). The lower jaw may also be abnormally short (undershot).

The brain of affected neonates may be grossly underdeveloped, resulting in clinical signs of a nervous nature – uncoordination, trembling, partial paralysis. In cattle SBV is also known to cause fever, milk drop, inappetence and diarrhoea in adult cattle at the time of infection (acute phase of disease immediately after infection by midge bite).

What is the highest risk period for cattle and sheep to contract the virus that will result in the greatest losses?

The greatest losses are associated with the development of deformed foetuses. The period of susceptibility in sheep is between day 28 and day 56 of pregnancy and between day 62 and day 170 of pregnancy in cattle. If ewes and cows at these stages of pregnancy are exposed to SBV-infected midges for the first time, they are at the greatest risk of producing a deformed foetus.

Immunologically naive, early lambing flocks which were synchronised appear to be the most severely affected flocks. The later lambing parts of such flocks tended to have fewer, if any, congenital abnormalities related to the virus.

Can animals become naturally immune to the virus?

Animals which have had a natural infection develop acquired resistance to the infection. Based on our current knowledge, we assume such animals are considered protected against further infection. However, this is a new virus to science and some questions cannot be answered, such as whether this immunity is life-long.

Are there any long-term health or production problems with animals which were infected with Schmallenberg virus?

Obviously deformed lambs and calves have no long-term future, even if they survive. However, once their dams recover from giving birth to them, and don’t develop any infections, there will be no long-term implications.

Is there a human health risk with this virus?

This condition is confined to ruminants and does not affect people.

What is the current situation in other countries in relation to Schmallenberg virus?

Disease due to SBV was first identified in the town of Schmallenberg in Germany in the autumn of 2011. Since then it has spread across Europe. Details of when it was first diagnosed in each country is shown in figure 2.

If my flock or herd was exposed to the virus last year what is likely to happen in this coming calving and lambing season?

SBV was first diagnosed in Ireland just over 12 months ago, having been first identified and diagnosed in Germany the previous year.

Therefore, our understanding of how the disease behaves is evolving. However, Akabane, a related virus that affects ruminants in Australia, provides us with clues as to how SBV may behave in Ireland.

Animals which have been exposed to the virus prior to pregnancy will develop an immunity and the disease is not likely to be seen in such animals.

In herds/flocks in endemically infected areas, any new infections are likely to be confined to younger animals (heifers and hoggets) and animals introduced to the herd from non-infected regions.

Q&A continued here

SHARING OPTIONS