It is a challenging time in New Zealand. With the average farmer there making a loss for the first time in a generation, the mood in the industry is bleak. The system of farming has changed from low cost to high cost and continues to evolve.

Some of this change has been driven by decisions made during the high payout years, where farmers tried to maximise returns by producing more milk, either by feeding more supplements such as palm kernel and grain, or by lifting post-grazing grass heights.

Now that the milk price has dropped, farmers are finding it very hard to shake off the habit of feeding meal, even though the majority are making a loss on every kilogramme of milk solids produced. A lot of the excellent grassland management skills that New Zealand farmers became famous for have been lost also.

The other big change is in environmental regulations. Now, consent (planning permission) from district councils is required for new dairy farms, with increased environmental scrutiny being applied to existing farms.

Ground water quality has been deteriorating for many years and dairy farming is getting the blame for this. Many farmers have been forced to build soiled water storage tanks and some district councils are imposing stocking rate limits and compulsory winter housing requirements.

This suggests that the competitive advantage of New Zealand dairy farming is being eroded, both by farmers making bad decisions and by regulators rightly imposing environmental restrictions.

However, it is always in a time of flux that opportunities are created and lessons are learned. Many of the farmers I met were still making money and looking to expand. The following is a summary of what I take home from the visit.

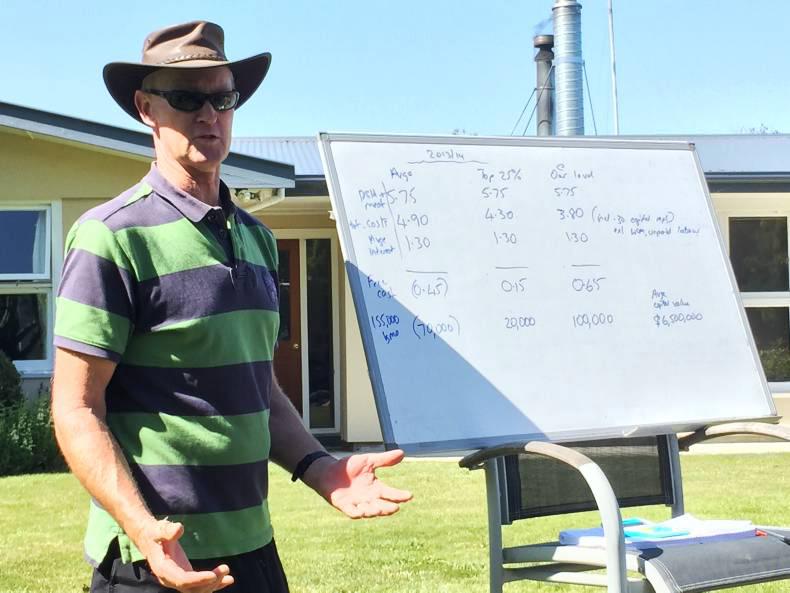

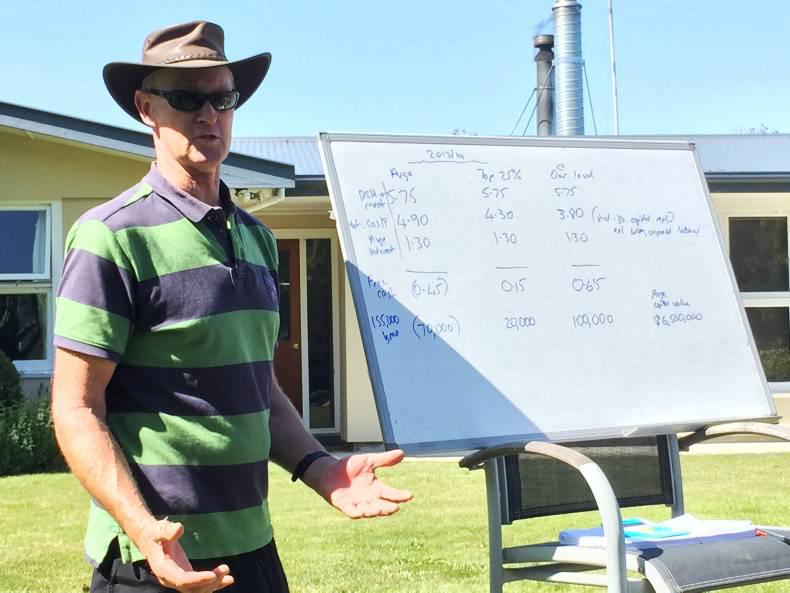

1 Chase EBIT not production: Earnings before interest and tax (EBIT) is what the top farmers use to analyse their businesses. Using EBIT/ha, they can quickly and easily compare investments based on the return on capital. To work out your EBIT, subtract all farm expenses, including your own labour but excluding interest charges, from total farm income. Divide this by the hectares farmed (total not just milking platform) to get EBIT/ha.

2 Return on capital drives investment decisions: EBIT divided by the total amount of capital invested will give the return on capital. Return on capital is used by all the top farmers to evaluate investments. The capital component should include stock, infrastructure and land purchase. When you know what your EBIT/ha is, evaluating investments is a simple calculation.

Generally, if the return on capital is lower than interest rates, then the investment is not worthwhile.

Some of the top farmers will only invest in something if the return on capital is predicted to be minimum 1.5 times greater than the interest rate.

To get a good return on capital, EBIT must be high and capital investment must be low. The interest rate at the moment in New Zealand is typically 6%.

3 Get the basic principles right: All the top farmers were very clear on the drivers of their businesses. Their system of farming didn’t just happen by accident – it was well thought out and geared towards being profitable in all milk prices.

The four pillars which underpin their systems are stocking rate, calving date, herd genetics and grazing management.

4 Stocking rate: This is determined by the amount of grass grown on the farm, particularly during the first six months of lactation. On some of the farms that are prone to drought, the stocking rate is higher than normal to maximise output per hectare before late summer and then animals are dried off or culled early to reduce demand later in the season.

Setting an appropriate stocking rate is a balancing act between getting high output per hectare and not having to rely too heavily on supplementary feeding. The best are feeding between zero and 300kg per cow.

5 Calving date: Calving is timed so that the herd is finished calving before grass growth takes off to maximise utilisation and avoid wastage.

A tight calving spread is essential to achieve this. Most of the farmers visited target a 10-week calving period with 50% of the herd calved in two weeks and 90% calved in six weeks. Having all the cows calved in a tight period really maximises milk solids output when grass growth takes off.

6 Genetic merit: High genetic merit cows are more efficient utilisers of grass, produce more milk solids and have a faster rebound after a period of feed shortage.

The New Zealand breeding index is called breeding worth (BW) and is similar to EBI.

The highest BW herds are all Jersey crossbred. Decisions surrounding what bulls to pick are easy. The majority use a team of bulls (premier sires) selected by LIC.

7 Grazing management: Strict grazing management is rigorously enforced on all the profitable farms. Leaving grass behind in the paddock is forbidden. The target grazing residual is never above 3.5cm.

The spring rotation planner is used to allocate the daily grazing area in spring. The feed wedge, rotation lengths and average farm cover are used to manage grass for the summer. The most important grass target is closing cover. This is close to 800kg/ha on many of the farms, with over-winter growth rates of 3kg to 4kg/day.

8 Body condition score: Having the herd in the correct body condition score (BCS) at drying off goes hand-in-hand with having the correct average farm cover at closing.

Cows will be dried off earlier to ensure they are in the right BCS at drying off and subsequently at calving. Cows will be culled if grass is behind target cover in autumn.

During the first rotation, grass covers and BCS gradually decreases. From the second rotation right through to the end of breeding, grass allocation and BCS will start to gradually increase.

9 Farm conversions: The advice from those who have done many farm conversions is put all the capital required in on day one and get the farm running at full capacity as soon as possible to maximise return on investment. Getting soil fertility corrected in year one was considered essential.

10 Financial control: On financial management, the top farmers all had an annual budget with monthly targets that were assessed at each month-end.

Alistair Rayne described the budget as being like a scoresheet that keeps the results, but the actions on farm will determine whether or not you win. “Financial discipline is never flirting with bad habits,” he said.

11 Fertility: Performance varied widely between farms. The best- performing farms did not use any intervention (prostaglandin, CIDRs, etc) or carry over empty cows to the next season. Instead, they bred cows that suited their system and only kept replacements from the first three weeks of calving from their most-fertile cows.

12 Advice: It was suggested that for young people starting off in the industry, they surround themselves with positive people and only take advice from those without a vested interest in selling something.

So what do Irish farmers need to do to stay profitable in all milk prices? By sticking with the principles outlined above, a grass-based, high milk solids-output system is the only obvious way forward.

I have yet to see a farm feeding high levels of meal or supplement per cow and getting good grass utilisation from grazing – anywhere in the world.

For me, feeding more than 700kg of supplement during lactation is high. The ideal is less than 500kg per cow, but I visited farms in New Zealand where no supplementation is fed and the farms still make money.

By focusing on return on capital, unnecessary capital expenditure on fancy parlours, robots, zero grazing machines, tractors and sheds will be curtailed.

Potential sires of the best cows to maximise EBIT, irrespective of breed, come to the top of the AI sire lists in New Zealand.

This should also be the case here in Ireland. For the best New Zealand farmers, Jersey crossbreds are a key part. From an industry perspective, we need strong leadership from our research and advisory body.

In my view, Dairy NZ are culpable in allowing a strong grass-focused dairy industry to sink into a mire of debt and distractions. Instead of keeping farmers focused on grass, it has been advising farmers how best to utilise feed pads, herd homes, meal feeders, etc.

Voices of reason within Dairy NZ have been silenced in favour of giving farmers the advice they want to hear, not what they need to hear.

Finally, we need to see more opportunities open up for young people interested in dairy farming in Ireland. New Zealand has a fantastic track record in creating win-win scenarios for young people without a farm of their own and existing land owners.

SHARING OPTIONS