Next Monday marks the 15th anniversary of the official end of the Land Commission. On 31 March 1999, the Commission became no more. The much derided entity had been part of Irish life and Irish agriculture since it was signed into law in 1881. For more than a century, the it was the body responsible for the redistribution of land in Ireland.

However, the Land Commission still casts a shadow over Irish farming and agriculture to this day. In certain cases, when lands were taken by the Commission and a neighbouring and productive farmer wanted the land to continue his or her development, the Commission distributed the land to a farmer hundreds of miles away.

According to the Central Statistics Office (CSO), of the 139,860 farm holdings operating in Ireland just 35,100 farms are in one block and 28,100 farms are in five blocks.

“It [the Land Commission] certainly created some anomalies,” historian John McCullen explained. “This happened when land from a farmer over the ditch from a neighbour came available. He wanted the land but because the farmer had no successor, the Commission took the land and gave to someone else,” he added.

The reasons for the creation of the Land Commission were twofold. Firstly, and perhaps most importantly, wealthy landlords were struggling for cash flow after the great famine. The landlords wanted to use what was at their disposal, large tracts of land, to improve their balance sheets.

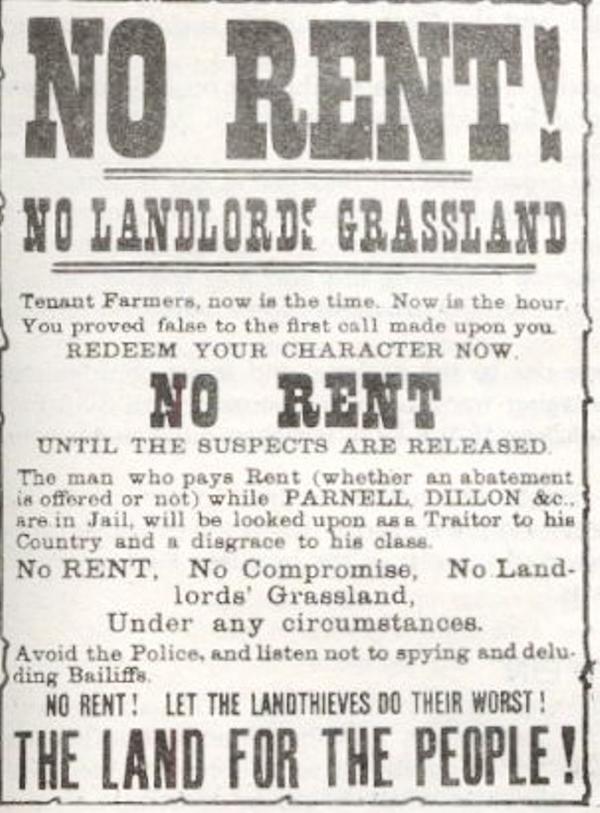

Secondly, the move to own land had taken on a new emphasis with the establishment of the Land League. The remnants of the famine not only have affected landowners but farmers too wanted the security of the ownership of land.

The Land Act of 1881 established the Land Commission which oversaw the sale of the land from the landlord to the tenants, usually at a price of 20-25 years worth of rent.

John McCullen explained: “The land holding system was at a bit of a crossroads. Approximately 15% of the people in Ireland owned 85% of the land, or something like that. The landlord or the people who owned the land had been living an exotic lifestyle with women and song. Many over-indulged outside the country. So, after the famine, they were short of money and saw the selling of land as a viable option.

“The hungry native wanted the land, and the security it brought, so it was a perfect fit. Three Fs from the Land League movement (fair price, free sale and fixity of tenure) were evoked. I suppose it was an early day John B Keane and the Bull McCabe,” McCullen said.

The heyday of the Land Commission was, perhaps, in the 1920s and 1930s when Éamon de Valera had the vision of uprooting farmers in the west of the country and who were Irish speakers into counties where land was underutilised, specifically in the east and north east.

Hence the 1932 phrase was born: “One more sow, one more cow, one more acre under the plough.”

McCullen said: “It was Dev’s great dream to bring Irish-speaking farmers from bad or marginal land in the west and south west and resettle them mainly in counties like Meath and Kildare, to bring the Irish language and culture to counties where it had been losing ground.

The whole system was poorly planned, though. Rather than vetting the farmers on suitability, the Commission, in most cases, simply chose the farmers who volunteered.”

The lack of planning resulted in some farmers who settled in the east returning to their farms in the west leaving the land to go through the commission again.

What are the legacies of the commission? There are clear and emotive feelings that remain over the body. Lands were taken and given to less productive farmers in cases. However, there are still those who benefited greatly from it. There are others who went from poor holdings to better quality farms and thrived. Also, land prices are considered to have been inflated considerably as a result of the Commission with farmers concerned over successors to the farm.

With the removal of dairy quotas in 2015 and access to land a concern for those looking to expand, is there a need to have a new Land Commission-style system to aid those looking for land around a parlour?

McCullen is not convinced.

“The ghost of the Land Commission I think would be too frightening for people to see a new version of the Commission set up. There remains huge hidden hostility towards what the Commission was and what the Commission stood for. The plan of a five or seven-year lease between farmer and landowner is much more, all-round, pleasing for all involved,” McCullen said.

In 1983, the commission ceased acquiring land and this was the beginning of the end for the entity. Some parcels of land continued to be signed off right up until 31 March 1999. The commission was taken over by the Department of Agriculture.

Next week, the Irish Farmers Journal will speak with descendents of those who were part of the Land Commission moves in 1930s and 1940s.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: