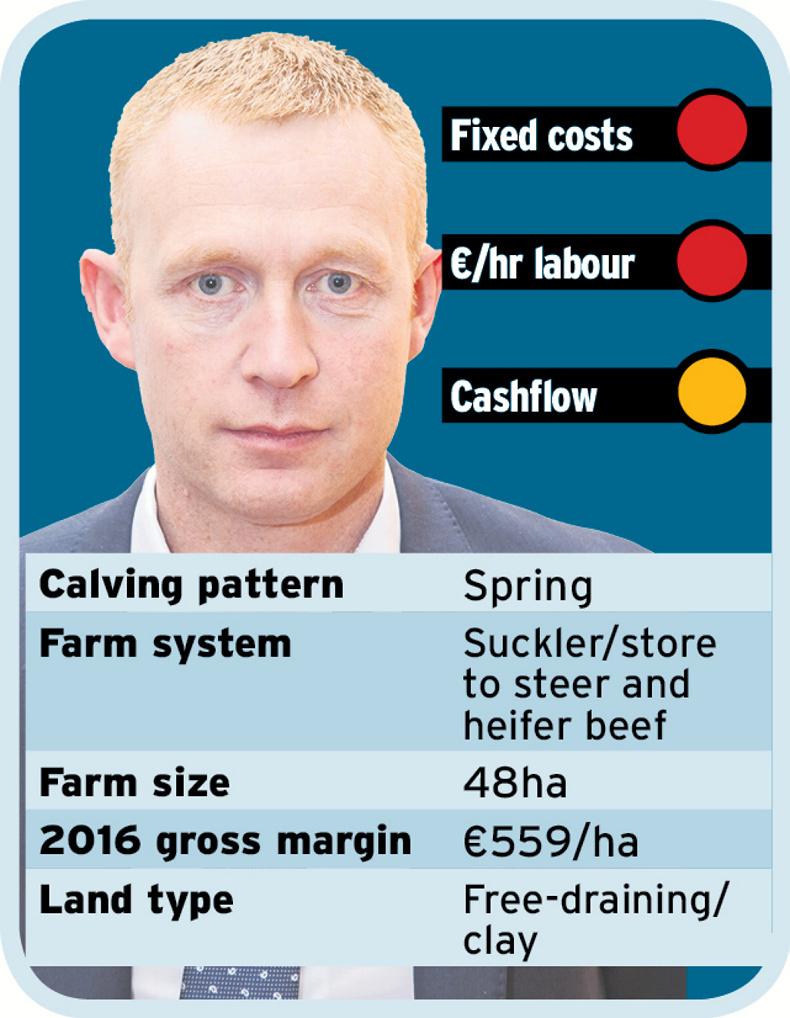

Brian Doran is flying the flag for Wicklow in phase three of the BETTER Farm beef programme. He farms 48 hectares near Carnew, in conjunction with his father, Pat. Brian’s wife, Deirdre, works in nursing and they have two children, Leah and Faye. The farm is split into three free-draining blocks of land.

Brian currently operates a suckler-to-beef system, slaughtering bullocks at 24 months of age and heifers slightly younger, at 20 months of age. Forty five cows calved down this year in the springtime and Brian’s plan is to push up to 50 suckler cows during the programme. Though he has the land to carry more, the fact that he mans the suckler side of the business largely on his own, and with the fragmented nature of the farm, Brian feels that 50 is a comfortable number for him.

The cows

The right raw materials are crucial for any business. Brian is blessed with land that has the potential to carry a long grazing season and an enviable cow herd to boot. There is quite a strong dairy influence in the herd, with the vast majority of Brian’s cows being either first cross or second cross from the dairy herd.

At Tullamore Farm’s open day this week, ICBF speakers talked of the importance of looking within the overall replacement when making breeding decisions – “for serious cattle breeders, stars alone shouldn’t be the focus any more”.

Brian’s cow herd is a good example of this. At €88 overall, he is just the wrong side of the five-star maternal index threshold. But, within this, his herd is +7.5kg for milk production (national average 4.99kg) and -1.09 days for calving interval (national average -1.14). Brian’s suckler herd carcase weight index value (which predicts the cow’s genetic influence on progeny weight-for-age) is low, at 7kg (national average 9kg).

To balance this out we look to our sire. In recent years, the problem with the national suckler herd has been the heavy terminal influence in its genetic base – commercial cows bred for rosette winning, not calf rearing. This led to the introduction of the BDGP and the drive towards the replacement index.

Beef injection

Brian has the complete opposite problem to fix, in that he needs a beef injection coming from his sire to counteract the dairy genetics in his cow. The bull currently working his herd is a classy Limousin, with excellent pedigree. Sired by Haltcliffe Dancer, his dam’s genetics stem from both the infamous Imperial and the Ardlea herd. He holds five stars on the terminal index and is exceptionally strong for both carcase weight (38kg – five stars) and carcase conformation (2.62 – five stars).

Visually, the bull has exceptional depth and consistent muscularity from the neck right back to the hind quarter. While weak from a maternal point of view (two star, negative milk, positive calving interval), Brian has these traits in spades in the cow herd. For me, this bull complements things excellently. So as to prevent a dilution effect on these traits, only a small number of the bull’s daughters are being kept, with Brian looking to source first-cross black Limousin replacement heifers from surrounding dairy farms, where possible.

Getting the genetic cocktail right on paper is all well and good, but is Brian’s mix of a milky cow and a terminal bull physically delivering on the ground? Is he getting calves with visual quality and high pre-weaning growth rates?

At the time of writing, Brian’s last calf weight was taken in the first week in June. At this point, his calves were, on average, 103 days of age and had achieved an average daily gain of 1.27kg (range 0.83 to 1.97kg) from birth, to weigh 169kg. As the images of Brian’s calves suggest, the dairy influence in his cow herd is having minimal effect on quality.

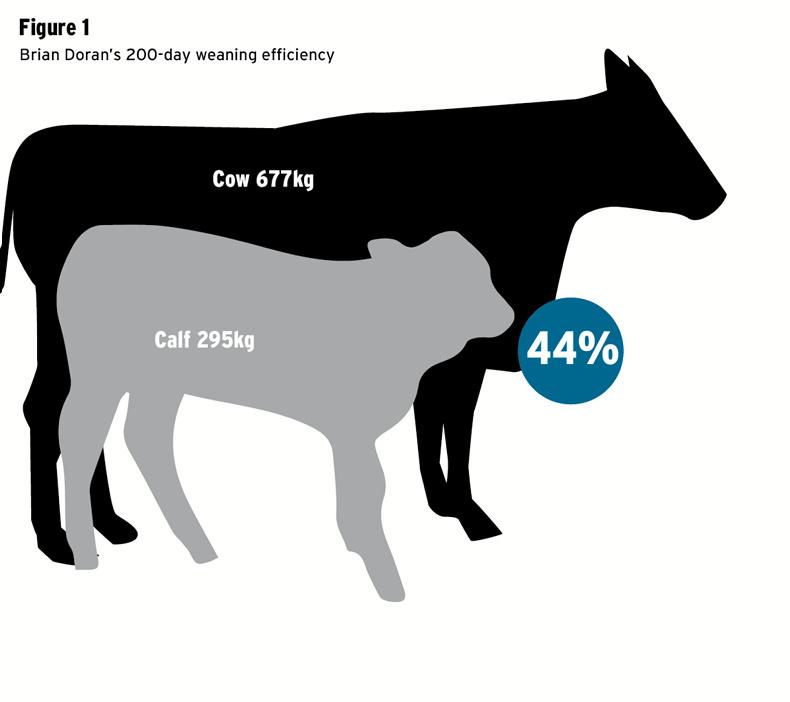

Weaning efficiency

One aspect of suckling that we will look to work on in the BETTER Farm beef programme is cow weaning efficiency. The overwhelming majority of the feed that a suckler cow eats goes towards her own maintenance, and the energy requirement for maintenance increases in tow with liveweight. In many of the big beef-producing nations around the world, feed is scarce. Farmers in these countries have bred handier cows (575-625kg) with lower feed requirements, which still produce weighty calves. Weaning efficiency is now an important measure when it comes to culling decisions, with a target of 50% set – that is, a cow should be weaning 50% of her body weight.

From an Irish point of view, we need informed discussion on two aspects of this figure before we can apply it across the board. The figure used in the UK and North America is ‘200-day calf weight’, yet we typically wean calves much older (and still struggle to reach the 50% figure as a whole). So where do we draw the line? Also, where do we stick the pin in cow weight – given its dynamic nature – when she has her work clothes on in mid-lactation or has fleshed up at weaning?

At 103 days, Brian’s cows weighed 677kg (ranging from 556kg to 876kg). If we assume that his calves remain growing linearly at the same rate – there is no reason why they shouldn’t – to 200 days and take this cow weight, Brian will achieve a weaning efficiency of 44% (295kg) in mid-September.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: