Fifteen members of the Whyte family derive an income from their family farm in the Naul, Co Dublin. They farm 3,000 acres, 1,000 of which they own and 2,000 of which are rented. Seven members of the Whyte clan – who range in age from 55 to 72 are farming alongside their seven sons, who range in age from 25 to 40. Mary Whyte runs the ship in the office.

The Whytes have been in the Naul since the 1720s and it’s fair to say they’re kingpins in the local community (though they’ll be mortified that I’ve written that). The Whyte family accounted for half the population of the local school at one stage, and at one point, half the football team was comprised of Whytes. This is no surprise given there are 36 Whyte grandchildren all living within one mile of one another.

The grandparents of these 36 grandchildren were Peter and Brigid Whyte, who began the original farming enterprise in 1942. Peter was from a farming family of three brothers and five sisters. He didn’t own land and when he got married he went out on his own and started contracting.

He then bought a small bit of land and was mainly interested in tillage – growing wheat and barley – but he had a great love for livestock too.

Peter and Brigid Whyte had eight children: seven boys and a girl. Two of these children, Ollie and his brother Peter Jnr, fondly remember their parents. They say their mother was an industrious and supportive woman who had a great friendship with all her daughters-in-law and brought hot dinners to her family in the fields.

Ollie and Peter say the business was very simple at the time. “There was no fertiliser and no spraying, but [our father] developed it over the years,” says Ollie. “Then we came along and he encouraged us to work on the farm with him.”

They say their father was very much a family man and liked to see the family stick together, but he was also good at helping people who were starting off. He was national ploughing champion in 1946/1947 and had a great interest in machinery. Peter Whyte had an old chamber combine from America and was one of the first people in the country to own a CLAAS combine.

The Irish Farmers Journal is shown photos of the combine, bought in 1951 – and the invoice for it. You got one headlight at the time and you had to pay extra for a second one.

“He was a progressive type of man in his way, and if you had ideas he would encourage you to pursue them,” says Ollie.

But it is his work ethic his children remember most (“He was a shocking hard worker”) and the Whytes attribute the success of their business today to this legacy.

Peter Jnr remembers: “My father always said: ‘Once you’re able to work hard, that will take care of most of the problems.’ If you think you’re going to be able to farm and not work hard, you’re not going to be successful. It’s as simple as that. And working hard means applying yourself to every aspect of the business, it’s a full package.”

farming footsteps

One by one, as they all finished school, the Whyte children went in to farming (apart from daughter Genevieve, but she shows great interest in the land and the business).

“We kept expanding as we went along,” says Peter Jnr. “The more mouths there were to feed, the more land we bought.”

Peter Whyte Snr had great hope one of his children would become a vet, but that didn’t happen. “We all just wanted to go home and farm,” says Ollie. “He was very progressive, but he also made room for that (expansion) to happen.

“Over the years we bought a bit of land and then paid for it. Then we would buy another bit of land, and that’s the way we worked. If you were interested in doing it and if you were willing to work hard then that was enough,” explains Ollie.

The business

The Whyte farm currently grows about 2,700ac of cereals each year: wheat, oats, barley, oilseed rape, beans and maize. The Whytes sell most of their grain on the futures markets, something they say is enabled by their scale. Their scale also allows them to buy hundreds of tonnes of fertiliser at a very good price.

They also share machinery. “We have a company that pools all the machinery and that keeps the cost down,” explains Ollie. “Everything that comes in and out of here is purchased like a producers’ group.”

The farm used to have a large contract for sugar beet, but they started growing potatoes in the mid 1990s to replace it. Today, their potatoes go to Tesco through Country Crest and their potatoes are in Dunnes Stores too. “We have our own drying system and storage for potatoes – we handle all of that,” says Ollie. “We can deliver potatoes from here every week of the year.”

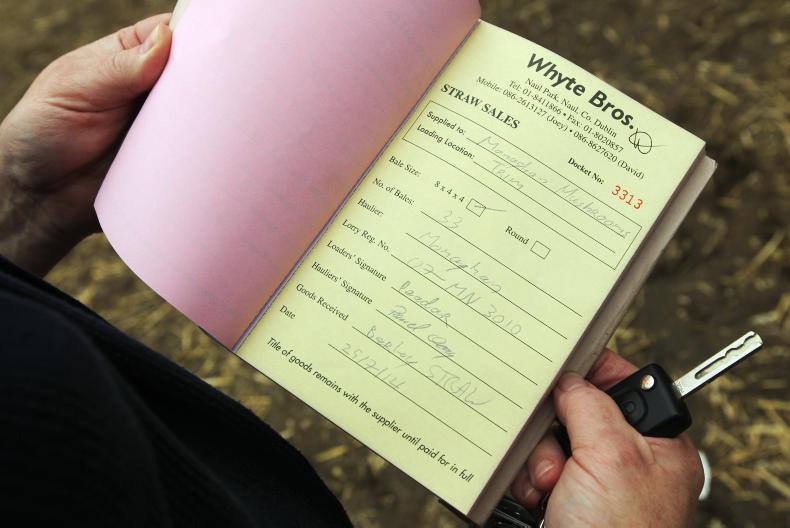

The Whyte also have a straw business and are Monaghan Mushrooms’ biggest suppliers (the mushroom industry uses straw in the compost mushrooms are grown in). They buy about 4,000ac to 5,000ac of straw each year, bale it up, stack it into ricks and deliver it to Monaghan Mushrooms. “We go into a farmer who cuts his corn and we buy the straw,” explains Joe Whyte.

There is a lot of livestock on the farm too – close to 600 head of cattle, to be precise – which are mainly heifers. “We supply Kepak with top-quality continentals,” says Peter.

And quality is something the Whytes place a lot of emphasis on. “If you have good quality you will sell at the best price on the day and the consumer wants it and the people you are dealing with will want it,” says Ollie.

We turn around and if most think that’s the way to go, then that’s the way we go. It’s a consensus thing

Various facets were added to the business gradually over the years – but never because it was dictated by a business plan.

“We would love to say we sat down and put a 10-year plan in place, but we didn’t. We just kept expanding. We had to go bigger,” says Peter. “As well as that, we didn’t all just come in at the one time. It was phased development and we increased the size to meet the needs.”

Dairy is almost the only farming enterprise the Whytes haven’t pursued. But it’s not for lack of interest – on the part of the older generation at least, some of whom were very keen to see the younger Whytes, like Kevin and Joe, turn their hands to milking.

“When trying to convince Kevin, we told him that cattle were a great way of keeping money together over the winter,” smiles Ollie. “His response was that an elastic band would do the same thing!”

All seven in the younger generation studied agriculture in college – whether that was in WIT, UCD or Warranstown. Does their expertise help the business? “If there is a bit of merit in their ideas, they are taken up,” says Ollie. “We are always open to new ways and moving forward. The lads would have a better technical knowledge.”

“But nothing beats experience!” laughs Peter.

With so many involved in the business, do they have regular meetings to make decisions? “A lot of people think we have some plan, that we sit down and there are all sorts of rules and regulations, but there’s not. There’s nothing like that,” says Kevin.

“Generally, if an idea comes up we talk it out and the downfalls will always be pointed out. Everyone has an area of responsibility. They are in charge and know their area. At the end of the day we would stand in the yard and chat anyway. Compared to a business, the same meetings happen, just in an informal way.”

“Generally, we play around and we don’t make decisions too quickly,” says Anthony Whyte. “We turn around and if most think that’s the way to go, then that’s the way we go. It’s a consensus thing. And if that decision is made then that’s gone, you move on.”

Anthony notes that having a larger number involved in decision-making can make it easier because “if two don’t agree with one another, then you have got other voices coming in.”

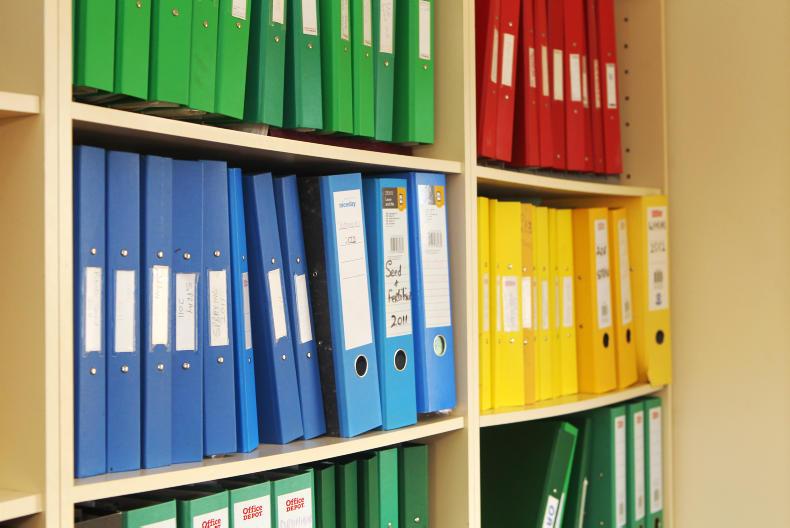

The farm is run through a computer, on which every field is logged, and every bit of corn is logged to every field, so the Whytes know the costs and the return of each field. Everyone owns their own land and then the Whytes rent a lot of conacre which is divided out among everyone.

When the younger generation “came home” first, they were given a share of the business. They were all given “their bits of land” and entitlements were applied for on behalf of each of them.

Although they have their own share in the business, each farmer is considered an employee too, and wages are paid by standing order every week.

There’s no doubt the administration of this business is more complicated than most. Mary keeps account of everything – and the eight or nine male Whytes the Irish Farmers Journal met during this interview (we lost count there were so many coming and going!) were very keen to stress that the farm would fall apart without her.

If the Whytes had their way, there would be space for another four or five of the younger generation in the business, but for now, it’s at capacity.

But it’s a capacity bigger than most!

SHARING OPTIONS