Often, the instant response from Ontario wheat-growers when they hear the Irish twang is: “We just can’t grow wheat like you guys do over there.” It is certainly true that wheat yields in Ontario are limited by weather, climate and distance from the equator. However, are bigger yields always better? In Ireland, we constantly push for higher yields with higher inputs, but higher costs follow and we often forget about profitability.

Poverty grass

A lot of growers here in Ontario actually refer to wheat as “poverty grass”. The simple fact is that growing wheat in Ontario isn’t sexy; corn or maize is the crop that everyone wants to talk about. Growers here are intensely focused on improving their corn yields and are doing this through increased spend on extra nitrogen, plus fungicides at tasselling.

In my mind, corn here is treated very similar to how wheat is treated back home. While it can provide the highest yields when weather co-operates, if it does not, yield is lost, costs are too high and profit is lost. In the recent past, wheat has been used as a type of break crop in a three-year crop rotation of soya beans, wheat and corn. While the image of poverty grass is hard to shake off, the more intensive wheat growers are now starting to focus on growing it profitably.

Ireland v Ontario

Here in Ontario, 2016 proved to growers and agronomists that they can produce the type of yields that we can. Early planting, in combination with a mild autumn, created perfect conditions for wheat yields last harvest.

I recently spoke at the FarmSmart Conference in Guelph, Ontario, where I asked the question: “Are bigger yields always better”? I also wanted to put the term poverty grass to bed. To do this, I did a case study comparing a local Ontario grower with my home farm in Stradbally, Co Laois.

The grower in Ontario had an average yield of 118 bushels (3.2t) per acre compared with 154 bushels (419t) per acre at home. The Irish wheat producer had higher yields (not surprising) and both growers sold the straw from the field leaving similar revenues. It was also interesting that both growers received the same price for their wheat in 2016 – $184.80/t.

Cost breakdown

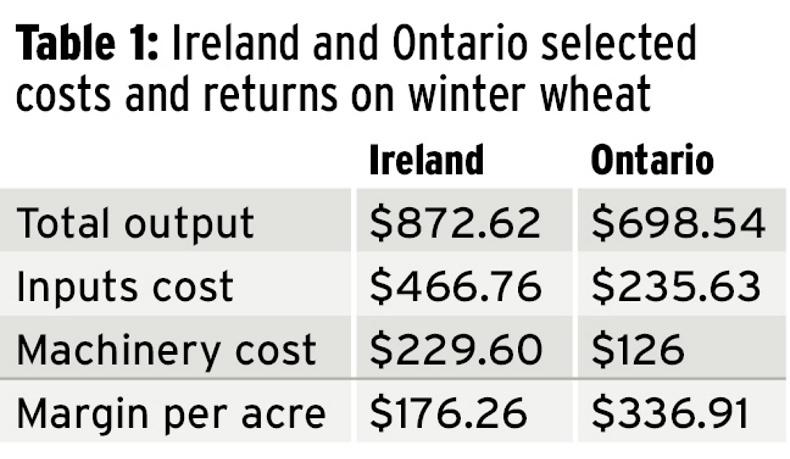

As you can see from Table 1, costs for both inputs and machinery in Ireland were a lot higher – almost double in both instances. There is less input applied in Ontario and this automatically leads to lower machinery costs.

The majority of wheat planted here in Ontario is either no-tilled or sown with one pass of a cultivator ahead of the planter. At home, we use a Horsch drill, with most fields ploughed and ring-rolled before seeding.

Seed costs are actually higher here compared with Irish certified seed. In Ontario, there are typically two fertiliser applications in the spring, with all the phosphorus delivered through the planter. The total nitrogen applied was 120lbs/acre or 134kg N/ha in Ontario – at home we apply 240kg N/ha. We also use three splits back home, leading to higher spreading costs.

The biggest difference in costs related to chemical inputs and their application. Here, most growers now apply two fungicides on wheat. The first is applied at T1 timing in conjunction with a broadleaved weed herbicide while the second was applied at early flowering.

There are some growth regulators registered here but they are generally not used due to the maximum residue limits for grain being exported to the US. At home, we applied four fungicide applications (T0 to T3), as is common for Irish growers. The reason for this is obviously the extremely high disease pressure in Ireland, especially from septoria.

When costs were all added up, we spent $189/ac on chemical inputs, almost six times the amount spent by the Ontario grower. These figures are absolutely scary. While we probably have the worst conditions for the spread of septoria in the world, we need to use as much good farming and agronomy practices as possible to help reduce this risk and chemical cost.

Efficiency and profitability

The two most important factors in producing cereal crops, whether that be in southern Ontario or in the Irish midlands, are efficiency of production and overall profitability. Despite our ability in Ireland to produce bigger wheat crops, we are much less efficient than our Ontario counterparts. From roughly 50% of our machinery and input costs, the Ontario grower can produce 70% of the overall Irish yield.

The Ontario grower had a net profit after all costs of $336.91/ac, almost double the profit on my home farm. There is a unique opportunity for Ontario wheat growers to produce wheat profitably and efficiently. In spite of the ‘‘poverty grass’’ tag, intensive producers want to grow better wheat crops. This is being done in conjunction with industry research and has enabled significant yield increases.

These growers constantly look to the Irish and UK model for producing wheat. They always want to hear about the production practices we use and how we manage crops to help achieve higher yield. Earlier maturing soya bean varieties are being planted to help get wheat planted in September. They have increased nitrogen rates and are now applying sulphur with these applications.

The intensive Ontario wheat grower is happy to listen to the merits of a T2 fungicide in a high disease year and will apply if necessary. While they look to our model in terms of production technology, Ontario wheat growers have now surpassed us in terms of profitability. We have a high-yielding environment in Ireland but that brings its own disadvantages, mostly in the form of septoria pressure.

I like wheat as a crop but as this disease adapts, we need to adapt to wider crop rotations and the use of other crops in the rotation that will help ensure the profitability of wheat in the future. Corn is the sexy crop here in Ontario, but wheat is profitable. In Ireland, we need to make our crops more profitable too.

Diverse rotations and the relatively poor performance of wheat traditionally caused it to be known as poverty grass in Ontario.Good husbandry and attention to detail has pulled the profitability of wheat right back up among the better performing crops.Cost of production per tonne is a very important element of efficiency, as is yield.

Often, the instant response from Ontario wheat-growers when they hear the Irish twang is: “We just can’t grow wheat like you guys do over there.” It is certainly true that wheat yields in Ontario are limited by weather, climate and distance from the equator. However, are bigger yields always better? In Ireland, we constantly push for higher yields with higher inputs, but higher costs follow and we often forget about profitability.

Poverty grass

A lot of growers here in Ontario actually refer to wheat as “poverty grass”. The simple fact is that growing wheat in Ontario isn’t sexy; corn or maize is the crop that everyone wants to talk about. Growers here are intensely focused on improving their corn yields and are doing this through increased spend on extra nitrogen, plus fungicides at tasselling.

In my mind, corn here is treated very similar to how wheat is treated back home. While it can provide the highest yields when weather co-operates, if it does not, yield is lost, costs are too high and profit is lost. In the recent past, wheat has been used as a type of break crop in a three-year crop rotation of soya beans, wheat and corn. While the image of poverty grass is hard to shake off, the more intensive wheat growers are now starting to focus on growing it profitably.

Ireland v Ontario

Here in Ontario, 2016 proved to growers and agronomists that they can produce the type of yields that we can. Early planting, in combination with a mild autumn, created perfect conditions for wheat yields last harvest.

I recently spoke at the FarmSmart Conference in Guelph, Ontario, where I asked the question: “Are bigger yields always better”? I also wanted to put the term poverty grass to bed. To do this, I did a case study comparing a local Ontario grower with my home farm in Stradbally, Co Laois.

The grower in Ontario had an average yield of 118 bushels (3.2t) per acre compared with 154 bushels (419t) per acre at home. The Irish wheat producer had higher yields (not surprising) and both growers sold the straw from the field leaving similar revenues. It was also interesting that both growers received the same price for their wheat in 2016 – $184.80/t.

Cost breakdown

As you can see from Table 1, costs for both inputs and machinery in Ireland were a lot higher – almost double in both instances. There is less input applied in Ontario and this automatically leads to lower machinery costs.

The majority of wheat planted here in Ontario is either no-tilled or sown with one pass of a cultivator ahead of the planter. At home, we use a Horsch drill, with most fields ploughed and ring-rolled before seeding.

Seed costs are actually higher here compared with Irish certified seed. In Ontario, there are typically two fertiliser applications in the spring, with all the phosphorus delivered through the planter. The total nitrogen applied was 120lbs/acre or 134kg N/ha in Ontario – at home we apply 240kg N/ha. We also use three splits back home, leading to higher spreading costs.

The biggest difference in costs related to chemical inputs and their application. Here, most growers now apply two fungicides on wheat. The first is applied at T1 timing in conjunction with a broadleaved weed herbicide while the second was applied at early flowering.

There are some growth regulators registered here but they are generally not used due to the maximum residue limits for grain being exported to the US. At home, we applied four fungicide applications (T0 to T3), as is common for Irish growers. The reason for this is obviously the extremely high disease pressure in Ireland, especially from septoria.

When costs were all added up, we spent $189/ac on chemical inputs, almost six times the amount spent by the Ontario grower. These figures are absolutely scary. While we probably have the worst conditions for the spread of septoria in the world, we need to use as much good farming and agronomy practices as possible to help reduce this risk and chemical cost.

Efficiency and profitability

The two most important factors in producing cereal crops, whether that be in southern Ontario or in the Irish midlands, are efficiency of production and overall profitability. Despite our ability in Ireland to produce bigger wheat crops, we are much less efficient than our Ontario counterparts. From roughly 50% of our machinery and input costs, the Ontario grower can produce 70% of the overall Irish yield.

The Ontario grower had a net profit after all costs of $336.91/ac, almost double the profit on my home farm. There is a unique opportunity for Ontario wheat growers to produce wheat profitably and efficiently. In spite of the ‘‘poverty grass’’ tag, intensive producers want to grow better wheat crops. This is being done in conjunction with industry research and has enabled significant yield increases.

These growers constantly look to the Irish and UK model for producing wheat. They always want to hear about the production practices we use and how we manage crops to help achieve higher yield. Earlier maturing soya bean varieties are being planted to help get wheat planted in September. They have increased nitrogen rates and are now applying sulphur with these applications.

The intensive Ontario wheat grower is happy to listen to the merits of a T2 fungicide in a high disease year and will apply if necessary. While they look to our model in terms of production technology, Ontario wheat growers have now surpassed us in terms of profitability. We have a high-yielding environment in Ireland but that brings its own disadvantages, mostly in the form of septoria pressure.

I like wheat as a crop but as this disease adapts, we need to adapt to wider crop rotations and the use of other crops in the rotation that will help ensure the profitability of wheat in the future. Corn is the sexy crop here in Ontario, but wheat is profitable. In Ireland, we need to make our crops more profitable too.

Diverse rotations and the relatively poor performance of wheat traditionally caused it to be known as poverty grass in Ontario.Good husbandry and attention to detail has pulled the profitability of wheat right back up among the better performing crops.Cost of production per tonne is a very important element of efficiency, as is yield.

SHARING OPTIONS