Between animal feed, food production and distilling, grain and feeds consumption in Ireland is more than 5m tonnes per year. But with Irish tillage farmers only producing between 2m and 2.5m tonnes of barley, wheat, oats and oilseed rape in any given year, there will always be a serious requirement for imported grain/feed in this country.

By far the largest imported type ofgrain is maize (corn), with close to 1m tonnes shipped into Ireland last year at a cost of €165m, according to figures from the CSO.

Maize has not always been such a major import ingredient for Irish feed, but the price dynamic of maize/wheat in recent years has seen imports soar. When maize prices were high – thanks to the US ethanol industry – Irish imports of maize were less than 400,000t per annum.

However, maize prices have fallen sharply in recent years as US ethanol production has plateaued and the US has become a net exporter of maize once again.

This has resulted in maize becoming more competitive than locally produced European wheat as a feed grain, even with the extra cost of shipping from the US, Canada or Ukraine. Huge global maize harvests also contributed to this price reduction.

This week on the Chicago grain market, the global benchmark, the US grain farmer is getting €126/t ($144/t) for maize. Freight and shipping costs of roughly €50/t mean maize prices off the boat in Ireland (ex-port) are €178/t. Depending on location, haulage costs to the feed mill will add a further €10/t to €15/t to this price.

Ireland imports maize from a multitude of destinations but just three countries account for almost two-thirds of imported volumes.

In 2016, Ukraine was the primary exporter of maize into Ireland, with over 265,000t shipped here. This was closely followed by the US with 230,000t, while Canada shipped 130,000t here.

The competitiveness of maize has displaced some of the demand for wheat by Irish importers.

In 2016, imports of unmilled wheat were just over 210,000t, with more than half of this coming from the UK. Denmark was the second-biggest supplier of wheat to Ireland last year, accounting for over a quarter (27%) of imports, or 58,000t.

For barley, almost all of the 90,000t imported came from the UK.

Protein

On the protein side, soya bean meal is the main protein source imported for use in animal feed. Roughly 500,000t of soya bean meal is imported every year ,with Argentina the number one supplier. The bulk of this soya bean meal is used to feed pigs and poultry, but the dairy herd is also a large user.

In Chicago this week, the US grain farmer will get just under €330/t ($377/t) for soya beans. Soya beans are then processed or “crushed” to create two separate products – soya bean oil and soya bean meal – which is used in animal feed.

Soya bean meal can be sourced in Chicago this week for less than €295/t ($337/t). With shipping costs similar to maize, at €50/t, soya bean meal off the boat in Ireland (ex-port) is priced at €340/t this week. Once again, haulage costs to the mill of €10/t to €15/t can be added to this cost price for Irish feed mills.

Depending on price, maize byproducts, such as distiller’s corn or gluten corn, may be used as a mid-level protein source for feed rations.

Comment: is there a benefit to inter-farm trading of grain?

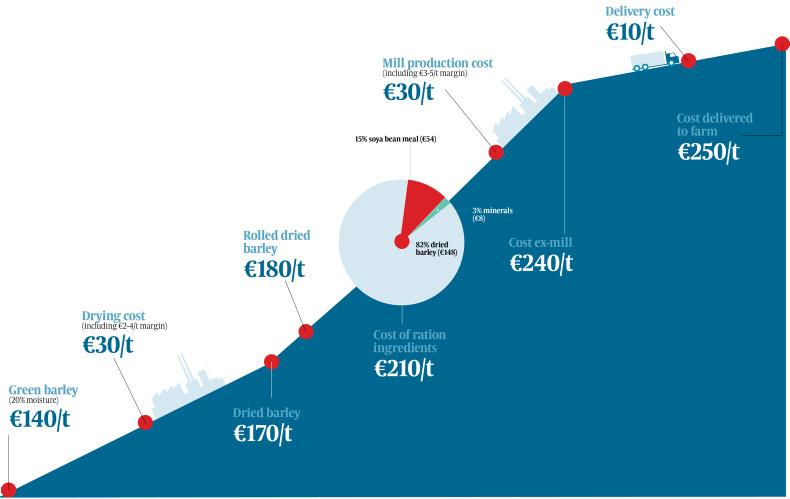

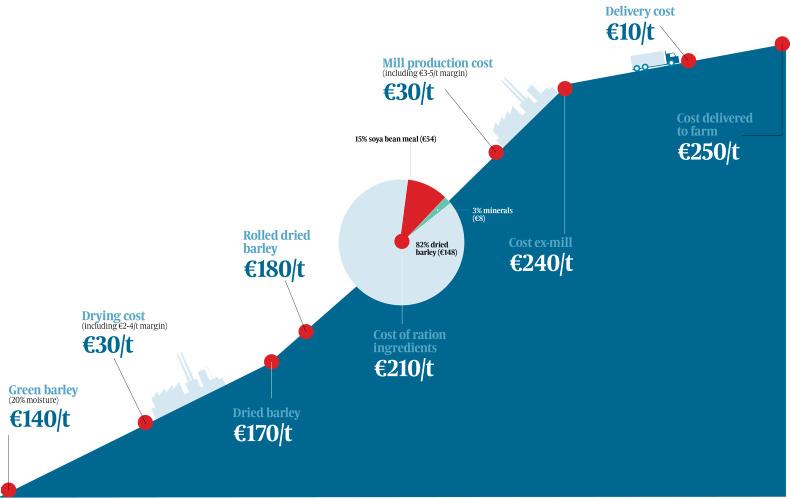

What does all this mean for a tillage farmer who may want to capture more of the chain and add value to his grain?

Firstly, while inter-farm trading makes sense on paper, in practice it is more complex and carries an element of risk. Looking at the various options available to a tillage farmer, the simplest would be to dry and roll barley.

Given the costs of drying and rolling, a further €5/t profit could be captured once all costs are paid. However, the additional investment made to capture this €5/t may not see any increased return.

If the grain farmer decided to make a coarse ration, the ration price in the example reflects actual costs of production and at most a €10/t profit margin. This profit level is required to cover the additional investment in drying, storing, rolling and mixing.

On the risk side, rather than selling at harvest, the volatility of the market is now borne by the grain farmer over the course of the year as feed sales continue for eight to 10 months post-harvest. While this can work to the farmers’ benefit in years where prices are increasing, the opposite is also true.

The feed buyer will require finance, which could be up to three months. This costs money. There is also the added complication of getting paid, collecting money and managing bad debts.

So, in conclusion, while inter-farm trading is an option, it is not for every tillage farmer and does involve significant investment and carries plenty of risk.

One of the benefits of the current merchant/co-op model is that last year – in a weak market – they paid above market prices for native Irish grain. One of the biggest weaknesses in the sector is the absence of a clear strategy to add value to Irish grain in a way that is returned to farmers. It’s a relatively small sector that needs greater joined-up thinking and stronger leadership.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: