The report puts processed meat in the highest category of certainty as a cause of cancer. It followed by putting red meat in general into the next category, which is defined as probably causing a link to cancer.

Processed meat is defined as meat that has “been transformed through salting, curing, fermentation, smoking or other processes to enhance flavour or improve presentation”. Red meat is defined as “all mammalian muscle meat, including beef, veal, pork, lamb, mutton, horse and goat”. Poultry and fish are excluded.

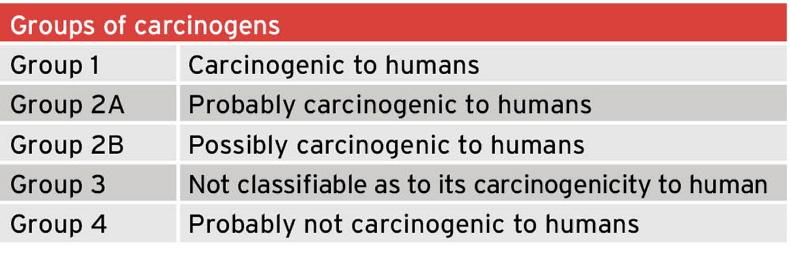

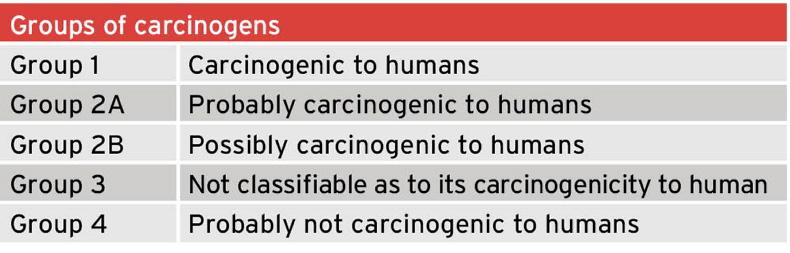

Carcinogens are a substance associated with cancer in humans and are classified into five categories according to IARC (see table).

What has caused outrage in the industry is putting processed beef into Group 1, which includes things like exposure to asbestos or smoking. This is a classic example of something being factually correct while at the same time completely misleading to a lay person, not reading with a scientific mind.

As explained by the Food Safety Authority of Ireland, this classification system indicates the weight of evidence as to whether an agent is capable of causing cancer – that is all. It is not a measure of the likelihood that cancer will occur as a result of exposure or the level of risk and is not an indication of how potent the agent is as a carcinogen.

Therefore, while both smoking and consumption of 50g of processed meat are correctly classified as Group 1, according to the report, it remains that smoking is considered to increase the risk of developing cancer by 600%, while consumption of processed meat at 50g daily increases the risk by 18%.

Even this creates an inaccurate suggestion. Using the example of a 50-year-old male: he has a 0.68% risk of developing bowel cancer within the next 10 years. If this was to increase by 18%, that brings the 0.68% risk up to 0.8%, still well under 1%, miniscule when compared with smoking, which increases the risk by a massive 600%.

This relatively simple comparison puts a totally different complexion on the report and allows consumers to put the risk in context. Over recent decades, there has been consumer overload with scientific reports on food risks and nutritional advice. That has resulted in many people becoming quite cynical and vox pops frequently reveal people being dismissive, saying they would continue to enjoy their rashers, sausages and black pudding as they always have.

When we learn that the report wasn’t unanimous, with up to seven members out of the 22-person agency abstaining, we can begin to understand why some people dismiss science. Doing so also misses the point. Study of disease causes requires study of scientific evidence by experts capable of understanding and assessing it. That involves an element of human judgement in weighing up the evidence and reaching a conclusion.

It is understandable that two equally qualified scientists could evaluate the same evidence and come to different conclusions. Therefore we have to base judgement on the weight of evidence and accept dissenting opinions.

Publication of reports like this would benefit so much from context and interpretation being published alongside. The initial sensational reporting has with time been replaced with balanced debate in the context of the by now well-explained risk. It is interesting and commendable that the Cancer charities and Food Safety Authority have been to the forefront of this, putting the risk in the overall context of lifestyle diet and behaviour.

SHARING OPTIONS