At the recent Farm Profit Programme Focus Group open day, we had a station demonstrating the Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) that drive profit in the suckler cow system. The first point in this is that the only variables that were examined were those that were controllable within the farm gate. This means that price and support payments have been set aside as we have no influence over them.

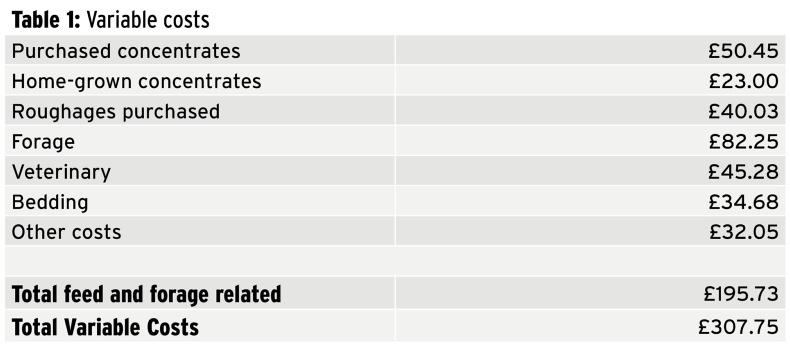

As price is excluded, in order to discover the real profit drivers, we need to look at the largest costs and the performance factors that have the greatest influence on them. To look further at the costs, Table 1 has been created using the data from the QMS Cattle and Sheep Enterprise Profitability in Scotland booklet.

This table has used the average data for each system explored in the booklet and averaged them all together to give a representation of suckler production in Scotland

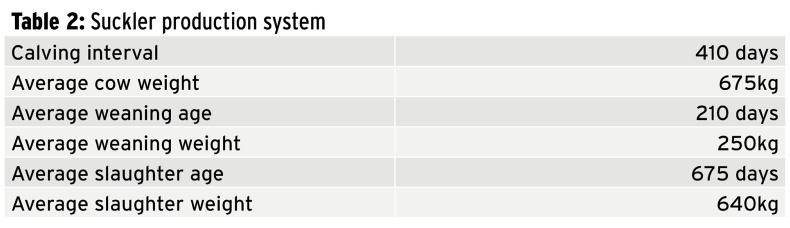

As can be seen in Table 1, feed and forage related costs make up nearly two thirds of all variable costs in the system, so it would seem logical to start with the feed costs. From here, we need to see what makes up the bulk of the feed costs. For this, we look at our suckler production systems. Table 2 summarises some details.

If the calf takes 465 days to gain 390kg between weaning and slaughter, then it will eat around 3.3t of dry matter over this period. If, however, its mother is the above average cow, weighing 675kg and taking 410 days between calves, this means that she will eat around 5.54t of dry matter per calf produced. If we give grazed grass a value and add up all of the dry matter utilised, the calf costs around £300 in feeding, whilst the cow costs nearly £450 in feeding.

Pulling all of this information together, it means that in order to have the greatest effect on the profit from selling a calf is to manage its dam’s feed costs. This can be achieved in several manners.

Firstly, shorten the winter

Preserving some grass in the autumn to ensure an early turnout in the spring is one of the greatest profit drivers that we can use. Around half of all suckler calves in Scotland are registered (and thus born) in March, April and May and being able to get cows out of sheds and on to grass as quickly as possible after calving will not only reduce feed costs but will also ensure that the cows’ lactation will peak as high as possible. This will mean a better supply of milk for the calf, leading to better weaning weights. It also means a significant reduction in disease pressure in sheds if calves are being turned out before excessive exposure to the disease buildup in the shed.

Having a plan to have some fertiliser on grass as soon as it is able to utilise the nitrogen will mean that the grass is ready for cows to be turned out on to. An inexpensive garden thermometer can be used to check the soil temperature at 10cm (4”) in the spring and once it is consistently above 5°C for a few days, the grass will utilise applied nitrogen. 30-40kg/ha of nitrogen (1cwt/ac of 27N product) at this stage will ensure that growth begins early.

Secondly, reduce the cost of winter

The cost of keeping a suckler cow through winter is the main cost in the suckler system. Reducing this has a significant effect on the profit margin. One way of reducing the cost of the winter is to make better use of straw. It may seem strange in a year when straw is expensive to feed more of it and yet when we look at a straw-based diet against a silage-based diet, although the straw consumed is certainly higher, the actual straw used due to reduced bedding requirements, can actually lead to less straw being used overall.

It is also worth pointing out that silage, when fully costed, costs somewhere in the region of £100/t of dry matter. Straw at £100/t delivered is equivalent to £116/t of dry matter. When feeding straw-based diets, cow intakes can be reduced significantly due to the bulking effect of the straw in the gut. This is partly why straw diets reduce straw usage. The other reason is that because there is little energy or protein in the straw, it does not pass through the cow as quickly, leading to drier bedding. Straw diets do need supplementing with protein to ensure that the rumen continues to work and the diet needs to be a minimum of 10% protein.

Arthur Duguid, one of the focus farmers is trialling 20 dry cows on a straw-and molasses-based syrup diet. So far, he is using around 3-4 bales less straw per week to feed and bed these cows against others in the same shed on a straw and silage diet. They will remain on this diet until mid-January and then move on to the same straw and silage diet pre-calving.

The cows chosen were fitter than the rest, however, they are now mobilising body condition and will be in CS 2.5 for calving.

These are the biggest effects and relatively simple to adopt in the short term. Longer term, cow size is the next profit driver. This is not an immediate effect as it takes time to change the makeup of a herd.

However, as the feed consumed to maintain a cow is directly related to her bodyweight, it does have a significant effect on the profitability of the herd. In order to gather the best data for this, weighing the cows and their calves at weaning and looking at the calf’s weight as a percentage of its mother’s bodyweight gives the best indication. It is then a simple case of choosing the heifers from the cows with the greatest weaning percentage as the replacements and selecting those cows in the herd that are not weaning a minimum percentage of their bodyweight for culling. Over time, this leads to a far more efficient herd and greater profitability.

Finally, in terms of the cow, the last key profit driver is the herd calving interval. The average herd in Scotland has a calving interval (days between calvings) of 410 days. Spread across the herd, this means that each cow is not producing for six weeks.

Those six weeks of lost production, mean an extra 0.5t of dry matter per cow is being consumed. This is equivalent to £35/calf being wasted in lost days. Culling empty cows and not giving them a second chance is a big part of fixing this and in order to expose them, a tight calving pattern is key.

None of these alone are a magic bullet, however, taken together, they can lead to gross margin improvements of around £200/cow. This is a significant difference in light of the current profitability of the sector.