As many dairy farmers grapple with the current low farmgate milk prices and wonder when they can expect a return to the halcyon days of 2013, some in the industry are questioning whether the current decline represents something more permanent.

Most analysts say we are experiencing a breakdown of the supply-demand balance and that the market fundamentals still point to a recovery during the first half of 2016. Although I agree a recovery is on the cards, I’m increasingly of the view that we are in the throes of a structural change in the global dairy commodity market and that the recovery will not be what many people expect.

If so, what does this mean for Irish dairy farmers?

Commodity cycles are a fact of life – demand for a commodity increases, supply follows and, generally, overshoots requirements, with a market correction causing prices to fall. When the price falls far enough, supply declines, demand outpaces supply, prices rise, and the cycle continues.

Complication

A further complication to this equation in dairy products is their luxury status. Their price is also dependent on the wealth of importing nations. This latter point is often forgotten in the argument that food prices will remain high because “people have to eat” and there is an ever-increasing number of people on the planet. Although it is true that the population is growing and that people have to eat, they don’t have to eat dairy.

For its nutritional composition, whole milk powder has been overpriced. If soya beans are €500/t, protein is worth approximately €1,000/t. Whole milk powder is only 25% protein. This puts its value at €250/t, purely for the protein supplied. Dairy protein is nutritionally superior to soya protein and should command a 100% higher price than soya protein on this basis. This puts its value at €500/t. It also deserves a premium for its functionality. However, we’re getting into the value-add space and not the basic nutritional needs of people who “have to eat”. In considering this, the lofty heights whole milk powder achieved during 2006 and 2013 reflected greater spending power in China and oil-exporting countries (due to high oil prices) and not a sudden increase in populations that “have to eat”.

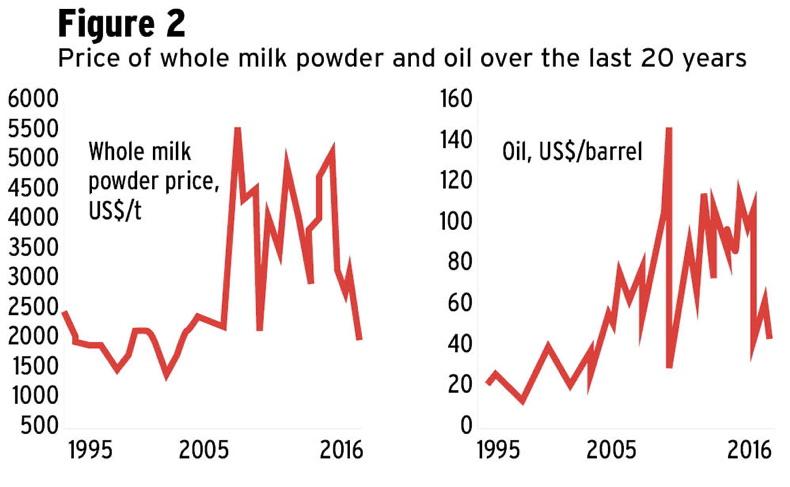

The current price is a reflection of over-supply of milk relative to demand. There was substantial growth in dairy production over the last 10 years, but it was the demand shocks that had the greatest influence on the depth of the downturn. Firstly, China artificially inflated apparent demand and price by purchasing beyond its needs in 2013. At the same time as China left the market in 2014, oil prices collapsed (from $110/barrel to $40/barrel) and sanctions and counter-sanctions with Russia removed major importers of dairy products from the global market. As a result, the supply-demand equation became even more imbalanced and price collapsed, dropping from US$5,100/t for whole milk powder in January 2014 to US$1,500/t in August 2015.

All of the indications are that this imbalance is being corrected through a lowering of milk supply, at least in New Zealand, and that this will lead to an upswing in prices globally through the latter half of 2015 or early 2016.

Although the markets appear to be correcting, I believe the basic fundamentals governing dairy commodities have changed and that we are in the throes of a long-term structural change that will influence the supply side of the equation and one which we ignore at our peril.

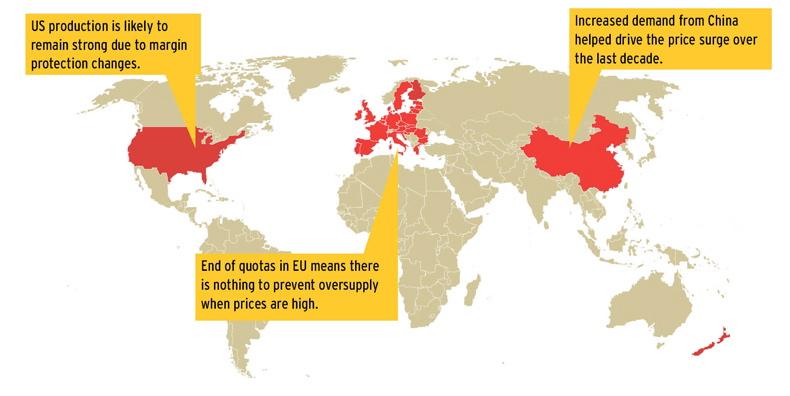

A decade ago, the removal of intervention stores coincided with significant economic growth in China. As a result, we saw a doubling of milk powder prices over the last 10 years when compared with the previous decade, albeit with greater short-term volatility around the mean.

I believe we are seeing equally large changes in the demand and supply for products, pointing to another structural change that will shape the milk price landscape over the next decade.

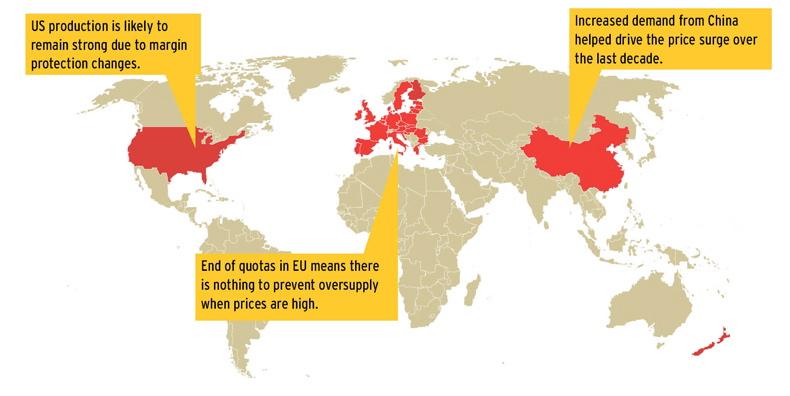

Arguably the most significant change is that the largest dairy producer in the world, the EU, is no longer constrained by quotas. This means quotas will no longer prevent an over-supply of milk when commodity prices are high.

This comes with a complication for export nations such as Ireland. Without a tiered pricing system for domestic and export milk in Europe, as is in place in the US, for example, domestic consumption within Europe inflates the price of milk received by the farmer during commodity market downturns.

Therefore, most European farmers are not receiving sufficiently strong signals to curb production. A 1% increase in milk production in the EU is equivalent to a 10% increase in New Zealand. Many are expecting a 5-10% increase in milk production in the EU with quotas gone.

Without a domestic market to absorb this increase, this is the equivalent to the entire production of New Zealand or about 30% more milk being traded globally. Even half of this projection would be a supply side game changer.

Furthermore, US farmers have had the opportunity to sign up to a margin protection programme. This means farmers can insure their margin over feed against drops in milk price. Low levels of insurance are virtually free, but even higher levels are inexpensive. For example, for a farmer to insure a margin over feed of 15c/litre, it would cost him around 2c/l.

More than half of all US farmers have taken out this insurance, with a higher proportion of larger farms members of the programme.

This programme could be a supply side game changer. Historically, when milk price dropped in the US, 5-10% of the national herd were removed from production. This automatically dropped supply and allowed prices to return to higher levels. With this insurance in place, even if milk price drops, farmers will be compensated for their milk up to the value of the insurance cover. In such a scenario, milk production will not slow down.

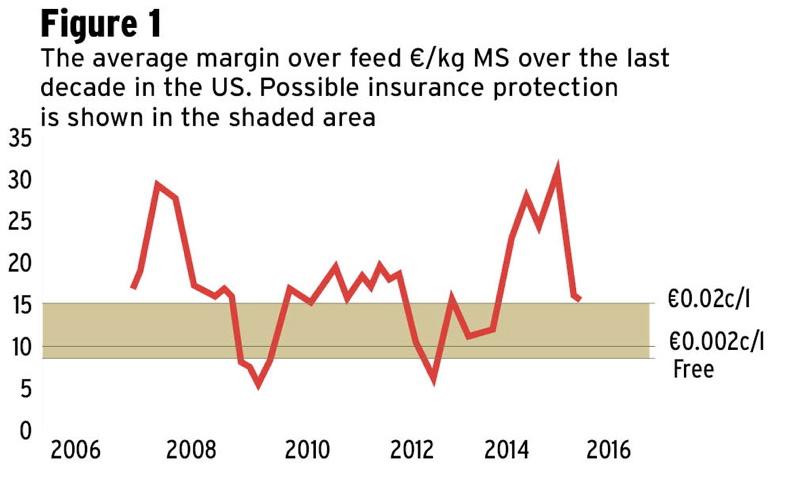

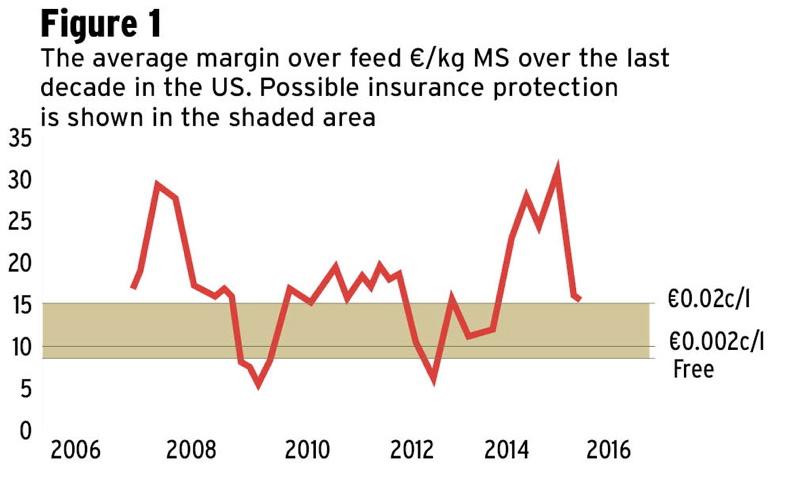

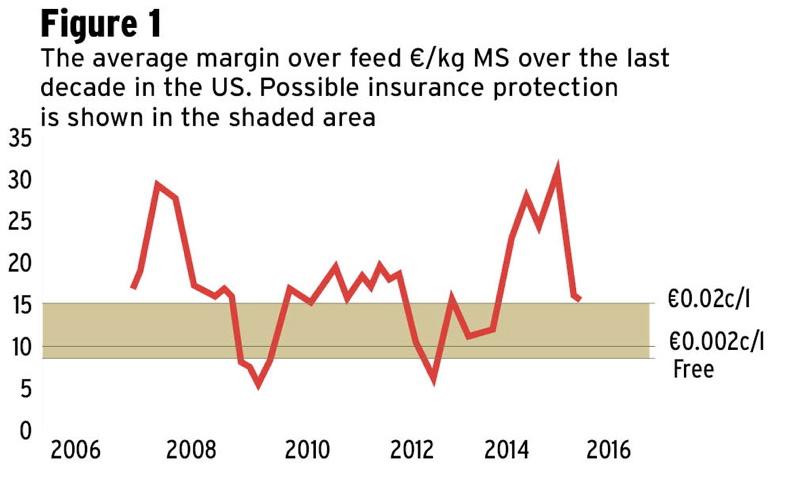

Figure 1 shows the average margin over feed in the US during the last decade. The shaded box highlights the level of insurance protection possible, with the premium cost for the different levels of protection highlighted on the right.

For example, insurance for €0.08/l margin over feed is virtually free, a €0.12/l margin over feed costs €0.002/l, and a €0.15/l margin over feed costs €0.02/l.

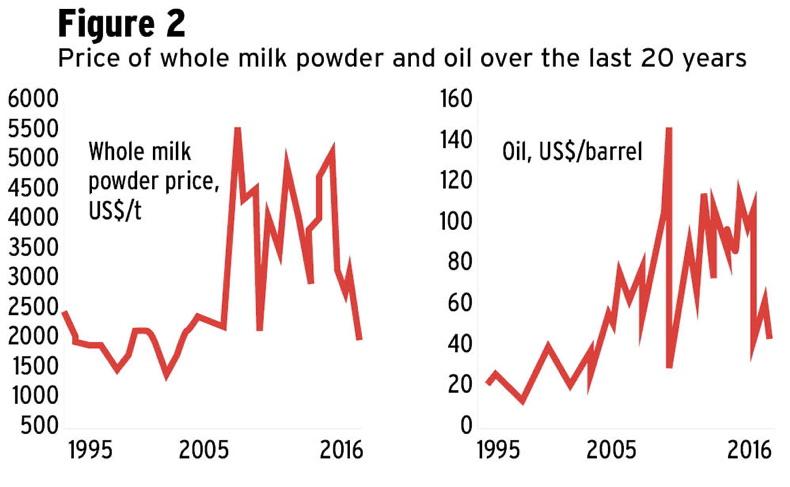

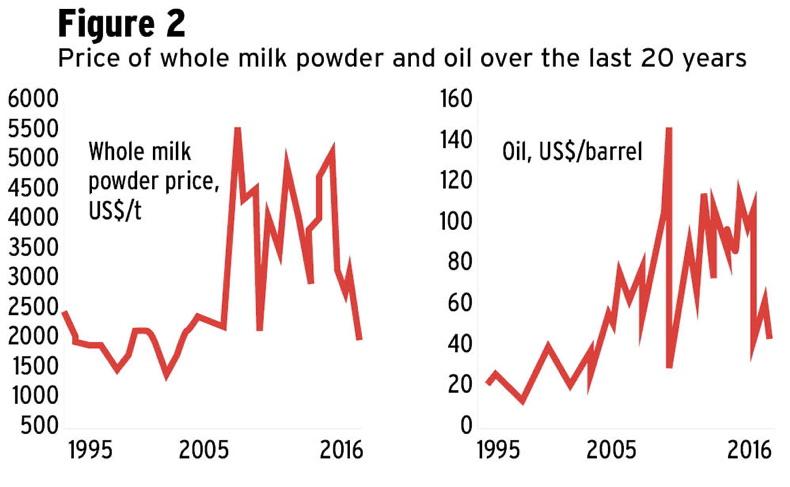

For the last two decades, the price of whole milk powder mirrored the price of oil (Figure 2). There are multiple reasons for this but, most notably, the cost of producing a tonne of whole milk powder increases with energy costs and the importation of dairy products (demand) by oil exporting nations increases with the price of oil.

During the last 18 months, oil prices have declined from more than US$100/barrel to US$40/barrel. This price is not likely to rise appreciably anytime soon, with reduced demand for oil due to the development of appreciable quantities of alternative sources of energy, most notably hydraulic fracking for shale gas.

Implications

Although the current low milk price is a result of short-term supply-demand imbalance, I believe that we are seeing a structural change in dairy commodity supply that will result in a return to lower milk prices than received between 2006 and 2015.

Although it is a dangerous game to be predicting milk price, we need to consider the range we are likely to receive if we are to set up our businesses to withstand the price shocks and avail of the high prices. For Irish farmers, long-term milk price is likely to sit close to €0.30, with peaks of €0.35 and troughs closer to €0.25 (ignoring shoulder payments). According to the Synlait milk price barometer, the value of milk supplied for export at the time of writing is €0.13.

Key messages haven’t changed:

Produce milk cheaply.Pay down debt and invest wisely in upswings.It has never been more important for Ireland to embrace the natural competitive advantage that its climate offers through grazed grass. Farmers must limit exposure to external market forces by limiting expenditure that does not result in more pasture consumed.

John Roche, PhD is from Castleisland, Co Kerry, and works in New Zealand. He is principal consultant at Down to Earth Advice Ltd.

As many dairy farmers grapple with the current low farmgate milk prices and wonder when they can expect a return to the halcyon days of 2013, some in the industry are questioning whether the current decline represents something more permanent.

Most analysts say we are experiencing a breakdown of the supply-demand balance and that the market fundamentals still point to a recovery during the first half of 2016. Although I agree a recovery is on the cards, I’m increasingly of the view that we are in the throes of a structural change in the global dairy commodity market and that the recovery will not be what many people expect.

If so, what does this mean for Irish dairy farmers?

Commodity cycles are a fact of life – demand for a commodity increases, supply follows and, generally, overshoots requirements, with a market correction causing prices to fall. When the price falls far enough, supply declines, demand outpaces supply, prices rise, and the cycle continues.

Complication

A further complication to this equation in dairy products is their luxury status. Their price is also dependent on the wealth of importing nations. This latter point is often forgotten in the argument that food prices will remain high because “people have to eat” and there is an ever-increasing number of people on the planet. Although it is true that the population is growing and that people have to eat, they don’t have to eat dairy.

For its nutritional composition, whole milk powder has been overpriced. If soya beans are €500/t, protein is worth approximately €1,000/t. Whole milk powder is only 25% protein. This puts its value at €250/t, purely for the protein supplied. Dairy protein is nutritionally superior to soya protein and should command a 100% higher price than soya protein on this basis. This puts its value at €500/t. It also deserves a premium for its functionality. However, we’re getting into the value-add space and not the basic nutritional needs of people who “have to eat”. In considering this, the lofty heights whole milk powder achieved during 2006 and 2013 reflected greater spending power in China and oil-exporting countries (due to high oil prices) and not a sudden increase in populations that “have to eat”.

The current price is a reflection of over-supply of milk relative to demand. There was substantial growth in dairy production over the last 10 years, but it was the demand shocks that had the greatest influence on the depth of the downturn. Firstly, China artificially inflated apparent demand and price by purchasing beyond its needs in 2013. At the same time as China left the market in 2014, oil prices collapsed (from $110/barrel to $40/barrel) and sanctions and counter-sanctions with Russia removed major importers of dairy products from the global market. As a result, the supply-demand equation became even more imbalanced and price collapsed, dropping from US$5,100/t for whole milk powder in January 2014 to US$1,500/t in August 2015.

All of the indications are that this imbalance is being corrected through a lowering of milk supply, at least in New Zealand, and that this will lead to an upswing in prices globally through the latter half of 2015 or early 2016.

Although the markets appear to be correcting, I believe the basic fundamentals governing dairy commodities have changed and that we are in the throes of a long-term structural change that will influence the supply side of the equation and one which we ignore at our peril.

A decade ago, the removal of intervention stores coincided with significant economic growth in China. As a result, we saw a doubling of milk powder prices over the last 10 years when compared with the previous decade, albeit with greater short-term volatility around the mean.

I believe we are seeing equally large changes in the demand and supply for products, pointing to another structural change that will shape the milk price landscape over the next decade.

Arguably the most significant change is that the largest dairy producer in the world, the EU, is no longer constrained by quotas. This means quotas will no longer prevent an over-supply of milk when commodity prices are high.

This comes with a complication for export nations such as Ireland. Without a tiered pricing system for domestic and export milk in Europe, as is in place in the US, for example, domestic consumption within Europe inflates the price of milk received by the farmer during commodity market downturns.

Therefore, most European farmers are not receiving sufficiently strong signals to curb production. A 1% increase in milk production in the EU is equivalent to a 10% increase in New Zealand. Many are expecting a 5-10% increase in milk production in the EU with quotas gone.

Without a domestic market to absorb this increase, this is the equivalent to the entire production of New Zealand or about 30% more milk being traded globally. Even half of this projection would be a supply side game changer.

Furthermore, US farmers have had the opportunity to sign up to a margin protection programme. This means farmers can insure their margin over feed against drops in milk price. Low levels of insurance are virtually free, but even higher levels are inexpensive. For example, for a farmer to insure a margin over feed of 15c/litre, it would cost him around 2c/l.

More than half of all US farmers have taken out this insurance, with a higher proportion of larger farms members of the programme.

This programme could be a supply side game changer. Historically, when milk price dropped in the US, 5-10% of the national herd were removed from production. This automatically dropped supply and allowed prices to return to higher levels. With this insurance in place, even if milk price drops, farmers will be compensated for their milk up to the value of the insurance cover. In such a scenario, milk production will not slow down.

Figure 1 shows the average margin over feed in the US during the last decade. The shaded box highlights the level of insurance protection possible, with the premium cost for the different levels of protection highlighted on the right.

For example, insurance for €0.08/l margin over feed is virtually free, a €0.12/l margin over feed costs €0.002/l, and a €0.15/l margin over feed costs €0.02/l.

For the last two decades, the price of whole milk powder mirrored the price of oil (Figure 2). There are multiple reasons for this but, most notably, the cost of producing a tonne of whole milk powder increases with energy costs and the importation of dairy products (demand) by oil exporting nations increases with the price of oil.

During the last 18 months, oil prices have declined from more than US$100/barrel to US$40/barrel. This price is not likely to rise appreciably anytime soon, with reduced demand for oil due to the development of appreciable quantities of alternative sources of energy, most notably hydraulic fracking for shale gas.

Implications

Although the current low milk price is a result of short-term supply-demand imbalance, I believe that we are seeing a structural change in dairy commodity supply that will result in a return to lower milk prices than received between 2006 and 2015.

Although it is a dangerous game to be predicting milk price, we need to consider the range we are likely to receive if we are to set up our businesses to withstand the price shocks and avail of the high prices. For Irish farmers, long-term milk price is likely to sit close to €0.30, with peaks of €0.35 and troughs closer to €0.25 (ignoring shoulder payments). According to the Synlait milk price barometer, the value of milk supplied for export at the time of writing is €0.13.

Key messages haven’t changed:

Produce milk cheaply.Pay down debt and invest wisely in upswings.It has never been more important for Ireland to embrace the natural competitive advantage that its climate offers through grazed grass. Farmers must limit exposure to external market forces by limiting expenditure that does not result in more pasture consumed.

John Roche, PhD is from Castleisland, Co Kerry, and works in New Zealand. He is principal consultant at Down to Earth Advice Ltd.

SHARING OPTIONS