Fusarium Head Blight (FHB), or ear blight, is an important fungal disease that affects wheat by reducing kernel weight, yield, and flour extraction rates in many important wheat-growing areas, including Ireland.

The extent of the losses depends on the severity of infection, the species of Fusarium involved in the infection, and on the environmental conditions prevailing at the time of infection. More than 15 Fusarium species have been isolated from infected wheat ears. Several of the species have been identified in Ireland, namely Fusarium avenacum, F. culmorum and F. poa, which produce mycotoxins such as DON (deoxynivelanol), fuminosins, zearalenone and T-2 (T-2 and HT-2) toxins.

The mycotoxins of primary concern is deoxynivalenol (DON) also known as vomitoxin, and produced by F. graminearum and F. culmorum. Since wheat grain is also the most traded cereal commodity, increasing concerns for food safety make breeding for FHB resistance a high priority although chemical intervention can help reduce losses.

Wheat is most associated with FHB and grains with severe Fusarium infection are typically shrunken. But this disease complex can also infect barley and oats, only the symptoms are less apparent since the kernels may not be shrunken. However, fungal growth may develop on the hull giving similar effects as with wheat.

Epidemiology

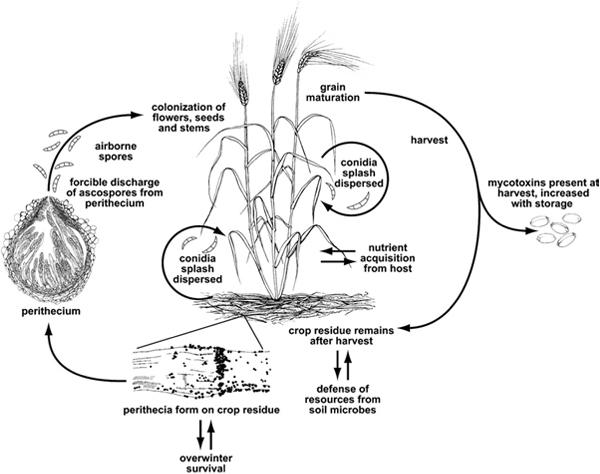

The initial point of a FHB epidemic cycle is an inoculum source, (eg crop debris, alternative hosts, Fusarium seedling blight and footrot of cereals) where Fusarium spp either survive as saprophytic mycelium or as chlamydospores (thick-walled asexual spores capable of surviving adverse conditions).

The fungus may subsequently infect the seedling, causing seedling blight and foot rot. Airborne and water-splashed conidia, as well as ascospores released from the source can infect wheat florets, resulting in FHB and new inoculum. Warm and moist weather conditions during wheat flowering and shortly thereafter promotes the germination of spores and the growth of fungal hyphae into grain tissues.

The process of penetration, infection and invasion of wheat ears by F. culmorum following spore germination involves the fungus producing a dense hyphal network on the host surface initially. After this infection, hyphae penetrate the inner surfaces of the developing grain, eg the lemma, glume, palea and the upper ovary. Parts of the grain (lemma and palea) can occasionally be invaded through the plant’s stomata and by intra and intercellular growth, where the fungal hyphae spread throughout the grain causing severe damage.

The mode of dispersal of inoculum to ears remains unclear, but contaminated insects, systemic fungal growth within the plant and wind and rain-splash dispersal of spores have been proposed. Infection of wheat ears occurs mainly during flowering and it has been demonstrated that fungal growth stimulants may be present in anthers which help to accentuate Fusarium infection during flowering.

Threat to plants

Plants inhabit environments that are crowded with infectious microbes which pose constant threats to their survival. Pathogens, such as Fusarium, are notorious for their aggressive disease causing ability which promotes plant death to secure nutrients for growth and reproduction from these dead cells. These factors help it exhibit a strong disease causing ability which contrast with the plant’s response to other pathogens such as Septoria. This makes Fusarium control more difficult.

The plant immune system, when effective, disarms infectious Fusaria species of their disease-causing arsenal. Simply inherited resistance traits confer protection against specific species. However, resistance to a broad range of Fusaria species is complex, thereby complicating its control. Components of resistance against Fusaria are currently being identified and this work offers some hope for enhanced resistance in future varieties.

Progress with resistance

Genetic resistance is generally characterised as Type 1 (resistance to initial infection) and Type 2 (slows the spread of the fungus within the ear from an infected spikelet to another through the rachis) but other mechanisms of resistance have been proposed in relation to their effect on DON.

Breeders and pathologists rely on visual scoring of disease symptoms and, now, the analysis of mycotoxins is also commonly used to assess tolerance in new lines. But these approaches are indirect methods and do not determine the accumulated fungal biomass involved in Fusaria infection. Relatively new molecular techniques, such as “Quantitative PCR”, can now be used to assess fungal biomass using its DNA. This could offer new possibilities to help develop Fusarium resistance in cereals and, particularly, in wheat.

In recent years, a quantitative PCR assay has been developed for trichothecene-producing Fusarium species. This has proven to be useful for the resistance assessment of wheat lines artificially infected with F. graminearum and F. culmorum. Techniques such as these will help in developing new lines with enhanced resistance to Fusaria species.

While the plant/disease interactions of FHB are complex, a greater understanding of these mechanisms along with new techniques in gene expression, should help provide the means to develop new strategies to control the disease.

Effect of straw length

A correlation between FHB resistance and plant height has been reported from earlier research findings. It is well known that work started by CIMMYT in the 1960s, saw dwarfing alleles intensively introgressed into elite wheat germplasm.

We now know that these dwarfing genes have a negative effect on FHB resistance in the field. A field study with near-isogenic lines in two genetic backgrounds of hexaploid winter wheat revealed a 35% and 52% higher FHB susceptibility when the dwarfing alleles Rht-B1 or Rht-D1 were present. This finding is supported by more recent research.

Chemical control

Fungicidal control of FHB is, at best, inconsistent and there are many reasons for this. Firstly, the inherent activity of molecules used for its control is only moderate due to the complexity of the organisms involved. Good activity against one Fusarium species may be masked by the subsequent growth of another. Secondly, there are real problems associated with application timing. And, thirdly, resistance to fungicides can develop quickly due to the complex nature of the FHB organisms.

Control options for FHB are limited. Research into plant breeding, an improved understanding of infection mechanisms and the genetic basis of resistance have only met with moderate success to date.While progress is being made regarding genetic resistance to FHB, no variety currently shows good Fusarium resistance.New plant breeding techniques and analysis tools may help sharpen the breeding effort. As well as a T3 fungicide, growers should minimise other risk factors such as wheat following maize and min-till establishment.Dry grain to 15% as soon as possible after harvest to help prevent mycotoxin production.

Fusarium Head Blight (FHB), or ear blight, is an important fungal disease that affects wheat by reducing kernel weight, yield, and flour extraction rates in many important wheat-growing areas, including Ireland.

The extent of the losses depends on the severity of infection, the species of Fusarium involved in the infection, and on the environmental conditions prevailing at the time of infection. More than 15 Fusarium species have been isolated from infected wheat ears. Several of the species have been identified in Ireland, namely Fusarium avenacum, F. culmorum and F. poa, which produce mycotoxins such as DON (deoxynivelanol), fuminosins, zearalenone and T-2 (T-2 and HT-2) toxins.

The mycotoxins of primary concern is deoxynivalenol (DON) also known as vomitoxin, and produced by F. graminearum and F. culmorum. Since wheat grain is also the most traded cereal commodity, increasing concerns for food safety make breeding for FHB resistance a high priority although chemical intervention can help reduce losses.

Wheat is most associated with FHB and grains with severe Fusarium infection are typically shrunken. But this disease complex can also infect barley and oats, only the symptoms are less apparent since the kernels may not be shrunken. However, fungal growth may develop on the hull giving similar effects as with wheat.

Epidemiology

The initial point of a FHB epidemic cycle is an inoculum source, (eg crop debris, alternative hosts, Fusarium seedling blight and footrot of cereals) where Fusarium spp either survive as saprophytic mycelium or as chlamydospores (thick-walled asexual spores capable of surviving adverse conditions).

The fungus may subsequently infect the seedling, causing seedling blight and foot rot. Airborne and water-splashed conidia, as well as ascospores released from the source can infect wheat florets, resulting in FHB and new inoculum. Warm and moist weather conditions during wheat flowering and shortly thereafter promotes the germination of spores and the growth of fungal hyphae into grain tissues.

The process of penetration, infection and invasion of wheat ears by F. culmorum following spore germination involves the fungus producing a dense hyphal network on the host surface initially. After this infection, hyphae penetrate the inner surfaces of the developing grain, eg the lemma, glume, palea and the upper ovary. Parts of the grain (lemma and palea) can occasionally be invaded through the plant’s stomata and by intra and intercellular growth, where the fungal hyphae spread throughout the grain causing severe damage.

The mode of dispersal of inoculum to ears remains unclear, but contaminated insects, systemic fungal growth within the plant and wind and rain-splash dispersal of spores have been proposed. Infection of wheat ears occurs mainly during flowering and it has been demonstrated that fungal growth stimulants may be present in anthers which help to accentuate Fusarium infection during flowering.

Threat to plants

Plants inhabit environments that are crowded with infectious microbes which pose constant threats to their survival. Pathogens, such as Fusarium, are notorious for their aggressive disease causing ability which promotes plant death to secure nutrients for growth and reproduction from these dead cells. These factors help it exhibit a strong disease causing ability which contrast with the plant’s response to other pathogens such as Septoria. This makes Fusarium control more difficult.

The plant immune system, when effective, disarms infectious Fusaria species of their disease-causing arsenal. Simply inherited resistance traits confer protection against specific species. However, resistance to a broad range of Fusaria species is complex, thereby complicating its control. Components of resistance against Fusaria are currently being identified and this work offers some hope for enhanced resistance in future varieties.

Progress with resistance

Genetic resistance is generally characterised as Type 1 (resistance to initial infection) and Type 2 (slows the spread of the fungus within the ear from an infected spikelet to another through the rachis) but other mechanisms of resistance have been proposed in relation to their effect on DON.

Breeders and pathologists rely on visual scoring of disease symptoms and, now, the analysis of mycotoxins is also commonly used to assess tolerance in new lines. But these approaches are indirect methods and do not determine the accumulated fungal biomass involved in Fusaria infection. Relatively new molecular techniques, such as “Quantitative PCR”, can now be used to assess fungal biomass using its DNA. This could offer new possibilities to help develop Fusarium resistance in cereals and, particularly, in wheat.

In recent years, a quantitative PCR assay has been developed for trichothecene-producing Fusarium species. This has proven to be useful for the resistance assessment of wheat lines artificially infected with F. graminearum and F. culmorum. Techniques such as these will help in developing new lines with enhanced resistance to Fusaria species.

While the plant/disease interactions of FHB are complex, a greater understanding of these mechanisms along with new techniques in gene expression, should help provide the means to develop new strategies to control the disease.

Effect of straw length

A correlation between FHB resistance and plant height has been reported from earlier research findings. It is well known that work started by CIMMYT in the 1960s, saw dwarfing alleles intensively introgressed into elite wheat germplasm.

We now know that these dwarfing genes have a negative effect on FHB resistance in the field. A field study with near-isogenic lines in two genetic backgrounds of hexaploid winter wheat revealed a 35% and 52% higher FHB susceptibility when the dwarfing alleles Rht-B1 or Rht-D1 were present. This finding is supported by more recent research.

Chemical control

Fungicidal control of FHB is, at best, inconsistent and there are many reasons for this. Firstly, the inherent activity of molecules used for its control is only moderate due to the complexity of the organisms involved. Good activity against one Fusarium species may be masked by the subsequent growth of another. Secondly, there are real problems associated with application timing. And, thirdly, resistance to fungicides can develop quickly due to the complex nature of the FHB organisms.

Control options for FHB are limited. Research into plant breeding, an improved understanding of infection mechanisms and the genetic basis of resistance have only met with moderate success to date.While progress is being made regarding genetic resistance to FHB, no variety currently shows good Fusarium resistance.New plant breeding techniques and analysis tools may help sharpen the breeding effort. As well as a T3 fungicide, growers should minimise other risk factors such as wheat following maize and min-till establishment.Dry grain to 15% as soon as possible after harvest to help prevent mycotoxin production.

SHARING OPTIONS