Like most modern celebrations, Halloween has become increasingly commercialised. Expensive costumes, flashy decorations and sugary sweets are now the mainstay in shops, as opposed to the simpler staples of nuts, apples and barmbrack, popular in years gone by.

Halloween marks the final and darkest quarter of the year, shrouding it in mystery. As agriculture was historically the country’s main occupation, with the harvest stored for the winter and the turf in, at Halloween time there was a certain security and a sense that people could unwind.

With roots in both the pagan festival of Samhain and the Catholic All Souls’ Day, Halloween is rich in custom, mostly surrounding the dead, and around the country in years gone by there were many unique traditions to celebrate.

In preparation for this article, I muse as to what would be the best way to access information on long-established and forgotten Halloween traditions. If only the people in the know were still around to ask. Well, many may not still be alive to tell the tale, but some have already told it.

The National Folklore Collection (NFC), established in 1935, documents people’s stories relating to all aspects of life, and of course the celebration of Halloween was among the topics covered.

Ríonach Uí Ógáin, a director of the NFC, outlines to Irish Country Living some of the material in the collection relating to Halloween. So too, some information from The Year in Ireland: Irish Calendar Customs by Kevin Danaher is used in this article. Most of the traditions and customs below would have been commonplace up to the 1940s.

Ghosts

In general, in the past people mingled more in the imagination. As Halloween signals the start of winter, it was often seen as a period when you could be exposed to other elements, ie ghosts, explains Ríonach.

It was a time when people perceived that the dead would be passing by and it was expected they would visit. Fairies, otherworld spirits and the púca would also be about and this was reflected in everyday actions.

“They lit candles, but the purpose of lighting candles was to accommodate both the dead and others. Say on Halloween, when you were throwing out water on the yard, you would say something like seachain – avoid – to warn them to stay away, that you were throwing water, something you might not do on other days of the year.

“With the dead, there wasn’t exactly a fear, it was an expectation and a respect. In some cases they left chairs out in the kitchen and food for them in case they were hungry. It was treating the dead as if they were alive.”

Of these immortals in folklore, the púca is the only one negatively perceived.

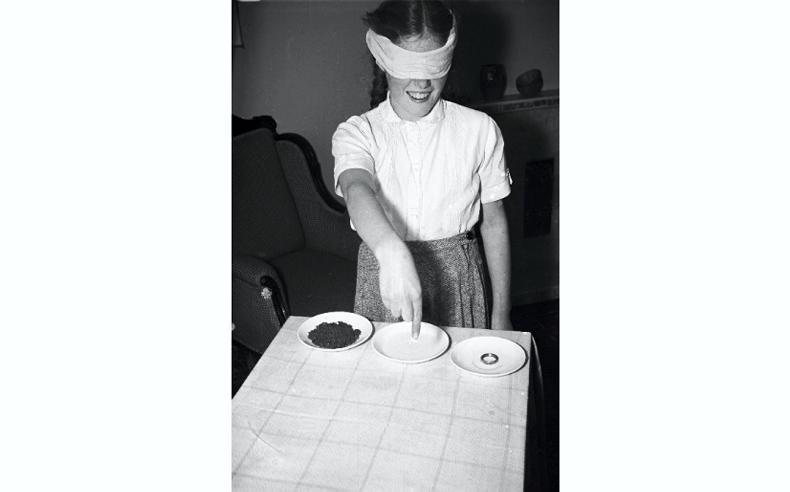

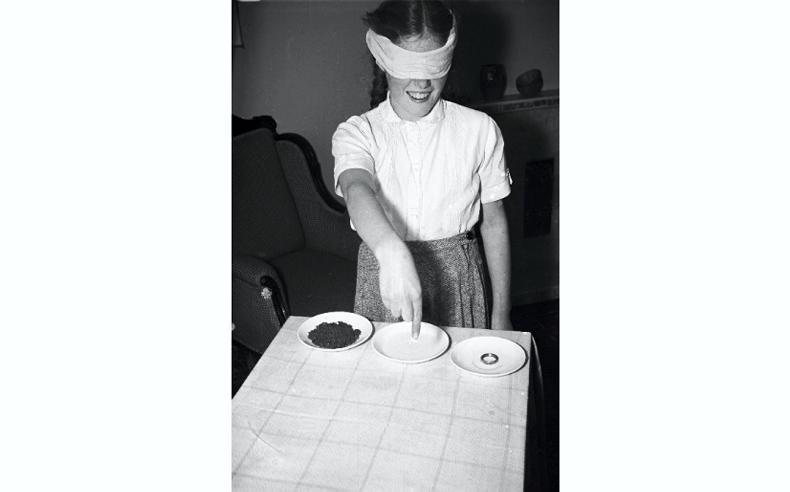

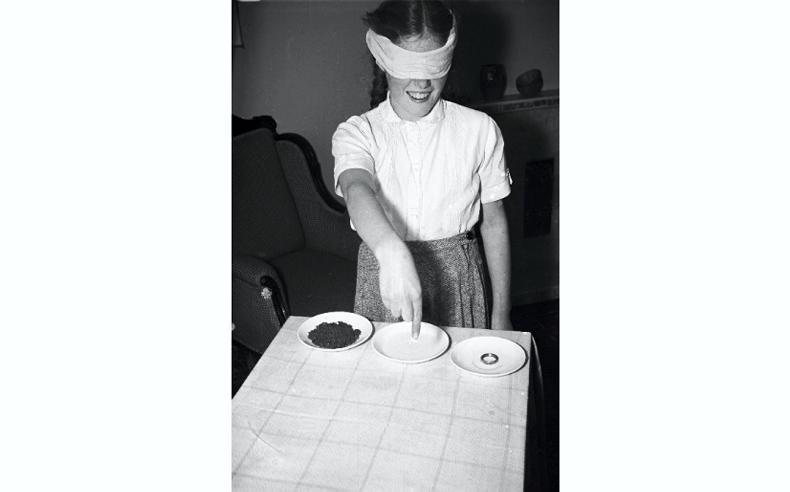

The girl in this photo is trying to find out about her future and is engaged in a game of divination. \ Maurice Curtain, courtesy of the NFC.

Divination

Another very strong belief relating to Halloween is that it was time when you could predict the future.

“Divination tied in with what Halloween represented, that it was a time when you could actually foresee what was going to happen, in a way that you couldn’t see on other days of the year,” says Ríonach.

“For example, what you dreamt on Oíche Shamhna was much more significant than what you might dream on the 3 or 4 November. If you dreamt of something on Halloween there was a greater chance it might come true.”

A photograph taken in Limerick during the 1940s exemplifies this idea of prophecy at Halloween acutely. It shows a girl, blindfolded, facing three dishes in front of her. Touching the dish of ash first means death, water means she will travel and the ring means she will get married soon.

Finding the ring in a barmbrack, taken circa 1935. \ Maurice Curtain, courtesy of the NFC.

Barmbrack

The Halloween treat of barmbrack was also a known tool of divination. The tradition of hunting for a ring in the sweet cake still holds firm today in many households. However, the meaning behind the ring and its previous accompaniments have since been slightly lost.

Long ago there would have been a ring, a pea, a stick and a piece of cloth all baked into the barmbrack. Each was a different omen for the person who found the object in their slice of cake.

Whoever found the ring would marry in the coming year, the pea would not marry, the stick would have an unhappy marriage or many disputes and the cloth symbolised a poor financial future.

Trick-or-treat

With regard to trick-or-treating, things were far different from the present day, although dressing up was still very common. Costumes were simple, mostly just masks fashioned from the back of Corn Flakes boxes, sometimes accompanied by a white sheet if a ghost was the desired effect. The food given out was mostly apples and nuts, sweets did not feature.

The trick side of things also varied slightly.

“The pranks and the tricks that were played on neighbours, they were dictated not just by social circumstance, but by economic circumstance,” outlines Ríonach. “In Connemara in the 1940s, I came across a trick that they would involve stealing the best couple of heads of cabbage belonging to a neighbour. It sounds very simple in today’s world, but at that time it was a big problem to lose three or four of your best heads of cabbage.” CL

Read more

Trick or treat - here's a tasty two-course Halloween offering

Halloween shopping tricks and treats

Like most modern celebrations, Halloween has become increasingly commercialised. Expensive costumes, flashy decorations and sugary sweets are now the mainstay in shops, as opposed to the simpler staples of nuts, apples and barmbrack, popular in years gone by.

Halloween marks the final and darkest quarter of the year, shrouding it in mystery. As agriculture was historically the country’s main occupation, with the harvest stored for the winter and the turf in, at Halloween time there was a certain security and a sense that people could unwind.

With roots in both the pagan festival of Samhain and the Catholic All Souls’ Day, Halloween is rich in custom, mostly surrounding the dead, and around the country in years gone by there were many unique traditions to celebrate.

In preparation for this article, I muse as to what would be the best way to access information on long-established and forgotten Halloween traditions. If only the people in the know were still around to ask. Well, many may not still be alive to tell the tale, but some have already told it.

The National Folklore Collection (NFC), established in 1935, documents people’s stories relating to all aspects of life, and of course the celebration of Halloween was among the topics covered.

Ríonach Uí Ógáin, a director of the NFC, outlines to Irish Country Living some of the material in the collection relating to Halloween. So too, some information from The Year in Ireland: Irish Calendar Customs by Kevin Danaher is used in this article. Most of the traditions and customs below would have been commonplace up to the 1940s.

Ghosts

In general, in the past people mingled more in the imagination. As Halloween signals the start of winter, it was often seen as a period when you could be exposed to other elements, ie ghosts, explains Ríonach.

It was a time when people perceived that the dead would be passing by and it was expected they would visit. Fairies, otherworld spirits and the púca would also be about and this was reflected in everyday actions.

“They lit candles, but the purpose of lighting candles was to accommodate both the dead and others. Say on Halloween, when you were throwing out water on the yard, you would say something like seachain – avoid – to warn them to stay away, that you were throwing water, something you might not do on other days of the year.

“With the dead, there wasn’t exactly a fear, it was an expectation and a respect. In some cases they left chairs out in the kitchen and food for them in case they were hungry. It was treating the dead as if they were alive.”

Of these immortals in folklore, the púca is the only one negatively perceived.

The girl in this photo is trying to find out about her future and is engaged in a game of divination. \ Maurice Curtain, courtesy of the NFC.

Divination

Another very strong belief relating to Halloween is that it was time when you could predict the future.

“Divination tied in with what Halloween represented, that it was a time when you could actually foresee what was going to happen, in a way that you couldn’t see on other days of the year,” says Ríonach.

“For example, what you dreamt on Oíche Shamhna was much more significant than what you might dream on the 3 or 4 November. If you dreamt of something on Halloween there was a greater chance it might come true.”

A photograph taken in Limerick during the 1940s exemplifies this idea of prophecy at Halloween acutely. It shows a girl, blindfolded, facing three dishes in front of her. Touching the dish of ash first means death, water means she will travel and the ring means she will get married soon.

Finding the ring in a barmbrack, taken circa 1935. \ Maurice Curtain, courtesy of the NFC.

Barmbrack

The Halloween treat of barmbrack was also a known tool of divination. The tradition of hunting for a ring in the sweet cake still holds firm today in many households. However, the meaning behind the ring and its previous accompaniments have since been slightly lost.

Long ago there would have been a ring, a pea, a stick and a piece of cloth all baked into the barmbrack. Each was a different omen for the person who found the object in their slice of cake.

Whoever found the ring would marry in the coming year, the pea would not marry, the stick would have an unhappy marriage or many disputes and the cloth symbolised a poor financial future.

Trick-or-treat

With regard to trick-or-treating, things were far different from the present day, although dressing up was still very common. Costumes were simple, mostly just masks fashioned from the back of Corn Flakes boxes, sometimes accompanied by a white sheet if a ghost was the desired effect. The food given out was mostly apples and nuts, sweets did not feature.

The trick side of things also varied slightly.

“The pranks and the tricks that were played on neighbours, they were dictated not just by social circumstance, but by economic circumstance,” outlines Ríonach. “In Connemara in the 1940s, I came across a trick that they would involve stealing the best couple of heads of cabbage belonging to a neighbour. It sounds very simple in today’s world, but at that time it was a big problem to lose three or four of your best heads of cabbage.” CL

Read more

Trick or treat - here's a tasty two-course Halloween offering

Halloween shopping tricks and treats

SHARING OPTIONS