The last place you want to find yourself, coming home from the pub or a dance, on Halloween night is at a lonely crossroads at midnight. Here you are in a prime time and space to encounter one of the many supernatural, otherworldly entities that terrifiy Irish people.

One might also of course come across the slua sidh ‘the fairy host’, the púca, the devil, the black dog or any number of old women, all up to no good. The one that always catches my interest is a notorious female called Petticoat Loose. There are numerous stories of the terrifying antics of Petticoat Loose from Dungarvan to Dingle and we have the wonderful folklorist Anne O’Connor to thank for bringing so many accounts together for us.

Petticoat got her name from her penchant for excessive drinking and spirited dancing in pubs and, on one occasion, such was the extent of her wild gyrations, her petticoat flew off. She is cast in the various accounts as a fallen and unrepentant woman and her name in itself suggests a sense of sexual profligacy.

Petticoat was a female force to be reckoned with and enjoyed wrestling men and competing with them in drinking contests.

Seemingly, she was for a time married to a hedge school master but tiring of his controlling nature, she murdered him and from there on in, she was extremely violent to all who confronted her.

The story goes that after one particularly excessive drinking bout when she was mercilessly egged on by the men, she consumed a complete surfeit and unexpectedly dropped dead with the bottle still in her hand. Terrified of the consequences, the men in the pub took her body and hurriedly buried her during the night on patch of no-man’s land near the crossroads.

Being a murderer, along with her low morals and subsequent burial without the blessing of a priest constrained her as a ghostly revenant that was confined to roaming the night and confronting men that passed by. Petticoat never attacked women.

There are numerous accounts of men travelling by horse and cart late at night and on coming to the crossroads seeing a woman on her own, they kindly offer her a lift. It is when she sits up onto the cart that her identity is revealed as the poor horse starts to struggle and sweat profusely. This huge extra burden was caused by her great weight. Petticoat’s weight came from her arms, each weighing one tonne and with a swinging blow from one of them she would kill all before her at will.

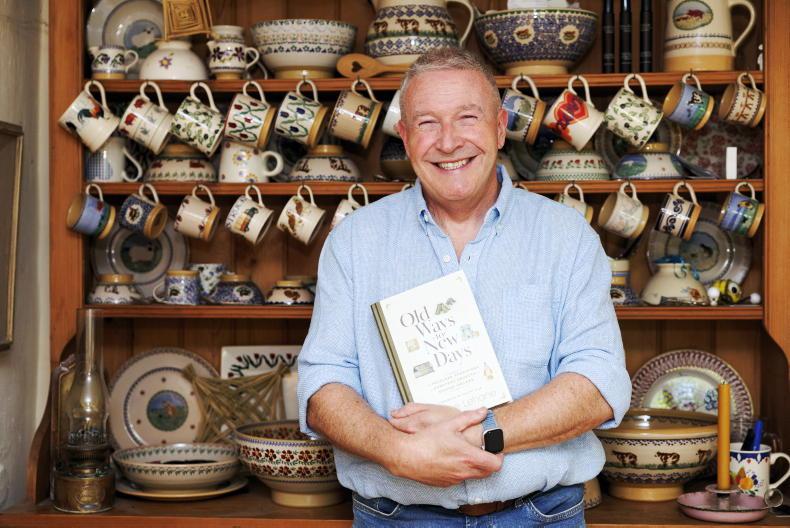

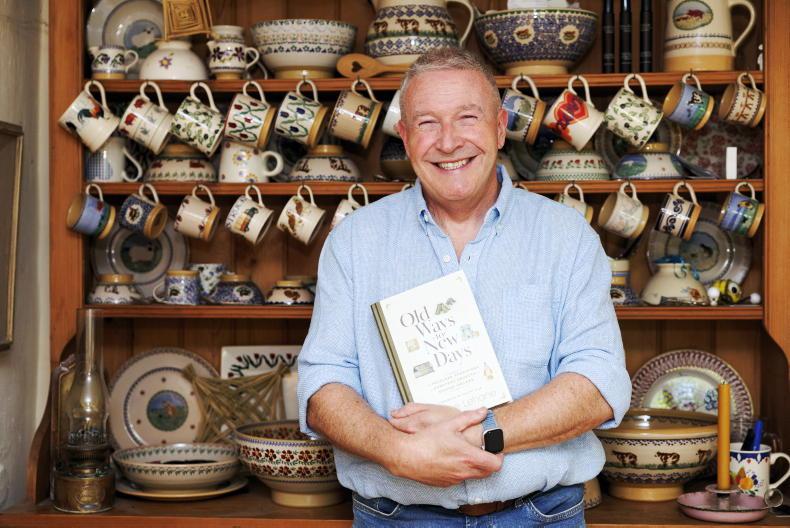

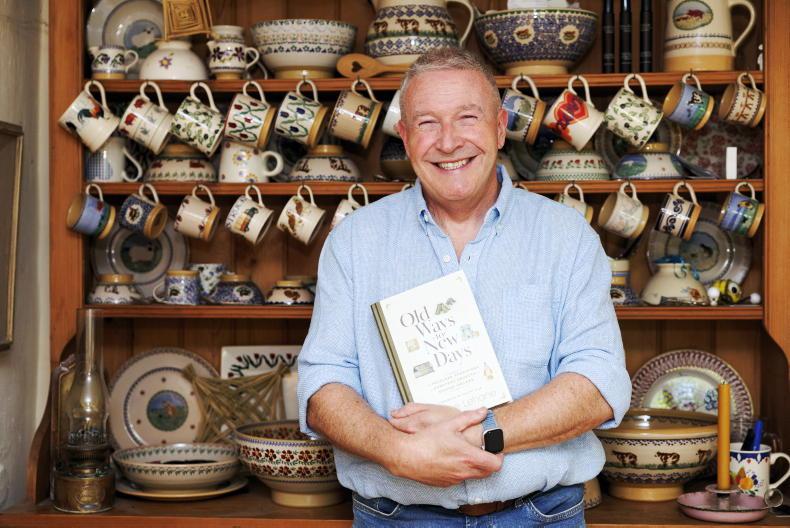

Shane Lehane, The Yellow House, Vicarsown, Co Cork. \ Donal O' Leary

Petticoat Loose strikes

In the stories, because of the initial kindness of offering her a lift, she allows some of the men to carry on, only if they promise to return the following night. In these cases, the men seek counsel from the parish priest who arrogantly dismisses their concerns, but the young curate comes to the rescue.

He advises them to wear a scapular and to bring holy water and pour a protective circle around themselves. The following night at the crossroads, when Petticoat comes along, she cannot get near him, and the man is terrified, but safe. The curate intervenes and tries to elicit a confession from Petticoat asking her what has caused her to be the way she is.

Petticoat lists her many wrongdoings from watering down the milk to beating her father and mother along with drinking and carousing while Mass was on.

However, it is her stark declaration that she was an abortionist, killing unbaptised children for payment and her complete lack of repentance that causes the curate to banish her. He condemns her and banishes her to spend rest of time at some never-ending tedious task such as emptying the Red Sea with a bottomless thimble or plaiting ropes out of sand.

Chauvinistic judgement

The emphasis on Petticoat’s excessive and nefarious activities speaks loudly of the male and church perspective on women in Ireland of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Petticoat is cast as the ultimate sinful woman, the epitome of all the so-called female vices. Scornful of all authority and social expectations, she flagrantly flaunts her independence in the face of all.

Condemnation of her comes not alone because of what she does, but moreover it is because she is a woman doing these things. Perhaps, it is best for us to hold back on any automatic, chauvinistic judgement of this complex female archetype and think again as to what the folk tales tell us about the prejudiced status quo.

Shane Lehane is a folkorists who works in UCC and Cork College of FEF, Tramore Road Campus. Contact: slehane@ucc.ie. Shane is author of Old Ways to New Days: The Folklore, Traditions and Everyday Objects that Shaped Ireland, published by Hachette Books Ireland, €18.99.

The last place you want to find yourself, coming home from the pub or a dance, on Halloween night is at a lonely crossroads at midnight. Here you are in a prime time and space to encounter one of the many supernatural, otherworldly entities that terrifiy Irish people.

One might also of course come across the slua sidh ‘the fairy host’, the púca, the devil, the black dog or any number of old women, all up to no good. The one that always catches my interest is a notorious female called Petticoat Loose. There are numerous stories of the terrifying antics of Petticoat Loose from Dungarvan to Dingle and we have the wonderful folklorist Anne O’Connor to thank for bringing so many accounts together for us.

Petticoat got her name from her penchant for excessive drinking and spirited dancing in pubs and, on one occasion, such was the extent of her wild gyrations, her petticoat flew off. She is cast in the various accounts as a fallen and unrepentant woman and her name in itself suggests a sense of sexual profligacy.

Petticoat was a female force to be reckoned with and enjoyed wrestling men and competing with them in drinking contests.

Seemingly, she was for a time married to a hedge school master but tiring of his controlling nature, she murdered him and from there on in, she was extremely violent to all who confronted her.

The story goes that after one particularly excessive drinking bout when she was mercilessly egged on by the men, she consumed a complete surfeit and unexpectedly dropped dead with the bottle still in her hand. Terrified of the consequences, the men in the pub took her body and hurriedly buried her during the night on patch of no-man’s land near the crossroads.

Being a murderer, along with her low morals and subsequent burial without the blessing of a priest constrained her as a ghostly revenant that was confined to roaming the night and confronting men that passed by. Petticoat never attacked women.

There are numerous accounts of men travelling by horse and cart late at night and on coming to the crossroads seeing a woman on her own, they kindly offer her a lift. It is when she sits up onto the cart that her identity is revealed as the poor horse starts to struggle and sweat profusely. This huge extra burden was caused by her great weight. Petticoat’s weight came from her arms, each weighing one tonne and with a swinging blow from one of them she would kill all before her at will.

Shane Lehane, The Yellow House, Vicarsown, Co Cork. \ Donal O' Leary

Petticoat Loose strikes

In the stories, because of the initial kindness of offering her a lift, she allows some of the men to carry on, only if they promise to return the following night. In these cases, the men seek counsel from the parish priest who arrogantly dismisses their concerns, but the young curate comes to the rescue.

He advises them to wear a scapular and to bring holy water and pour a protective circle around themselves. The following night at the crossroads, when Petticoat comes along, she cannot get near him, and the man is terrified, but safe. The curate intervenes and tries to elicit a confession from Petticoat asking her what has caused her to be the way she is.

Petticoat lists her many wrongdoings from watering down the milk to beating her father and mother along with drinking and carousing while Mass was on.

However, it is her stark declaration that she was an abortionist, killing unbaptised children for payment and her complete lack of repentance that causes the curate to banish her. He condemns her and banishes her to spend rest of time at some never-ending tedious task such as emptying the Red Sea with a bottomless thimble or plaiting ropes out of sand.

Chauvinistic judgement

The emphasis on Petticoat’s excessive and nefarious activities speaks loudly of the male and church perspective on women in Ireland of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Petticoat is cast as the ultimate sinful woman, the epitome of all the so-called female vices. Scornful of all authority and social expectations, she flagrantly flaunts her independence in the face of all.

Condemnation of her comes not alone because of what she does, but moreover it is because she is a woman doing these things. Perhaps, it is best for us to hold back on any automatic, chauvinistic judgement of this complex female archetype and think again as to what the folk tales tell us about the prejudiced status quo.

Shane Lehane is a folkorists who works in UCC and Cork College of FEF, Tramore Road Campus. Contact: slehane@ucc.ie. Shane is author of Old Ways to New Days: The Folklore, Traditions and Everyday Objects that Shaped Ireland, published by Hachette Books Ireland, €18.99.

SHARING OPTIONS