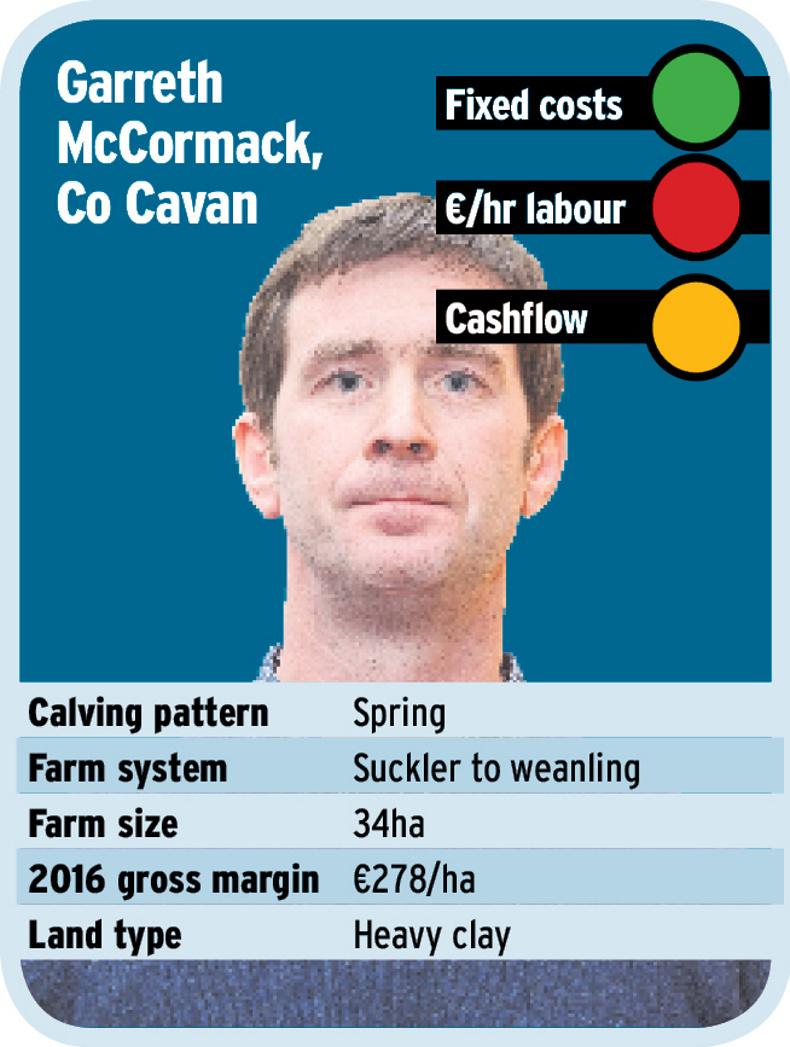

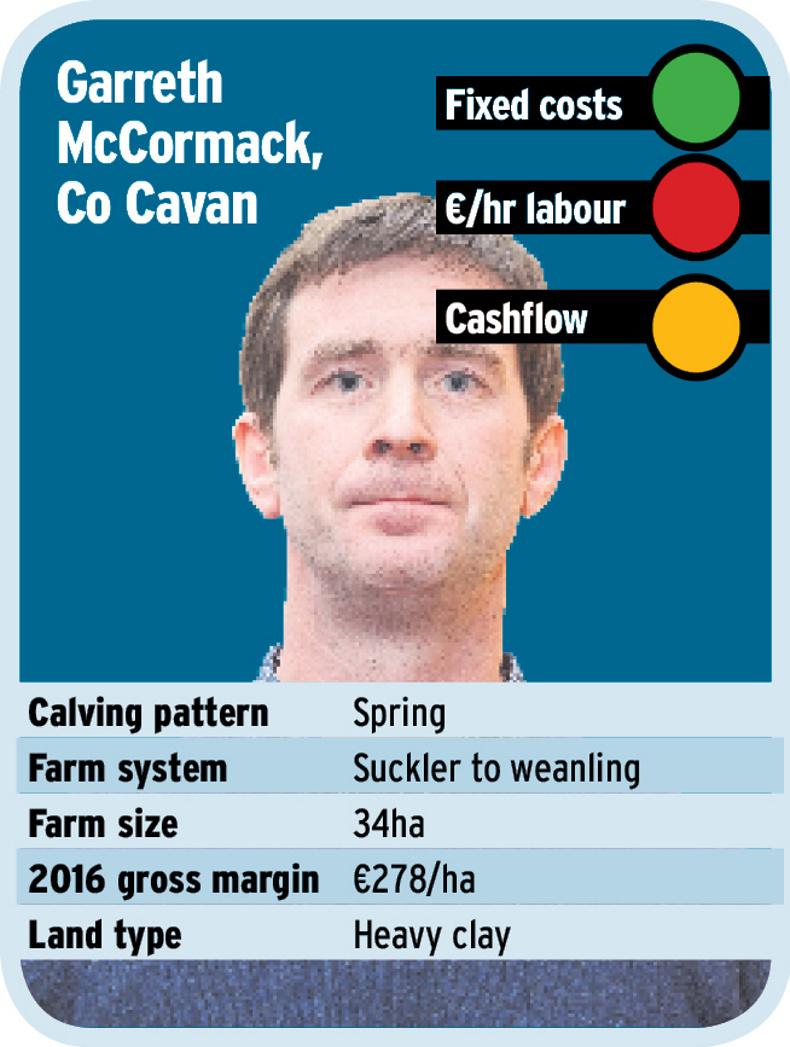

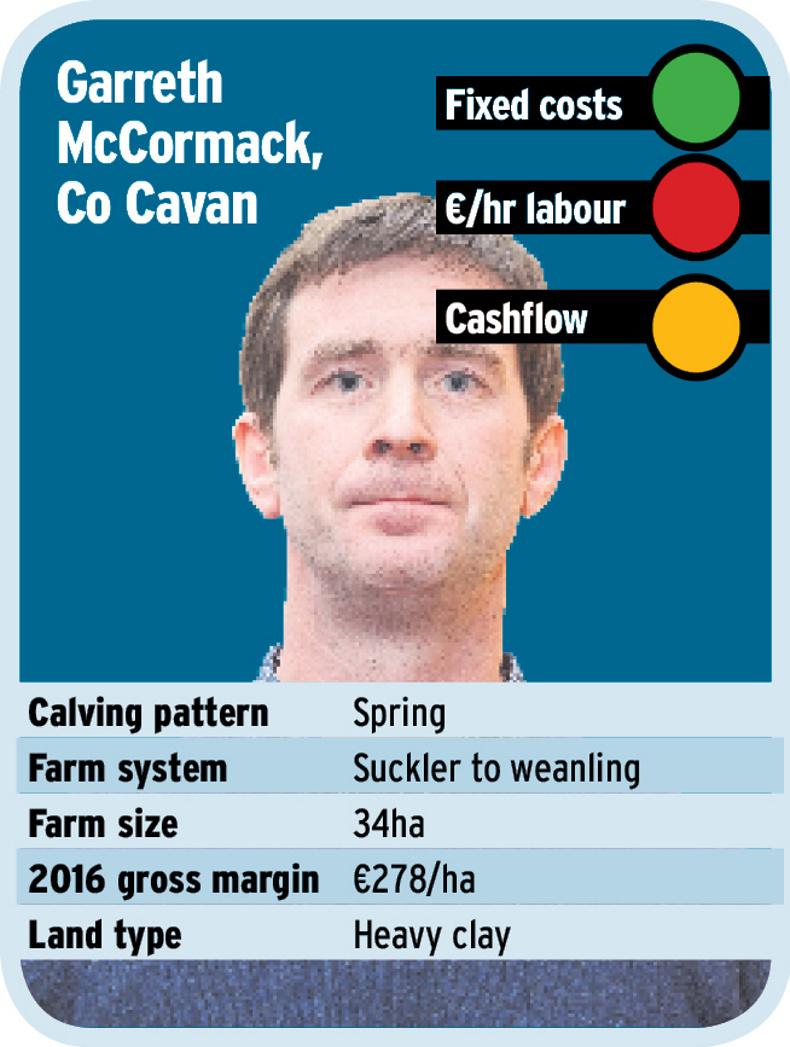

Garreth McCormack is Cavan’s representative in phase three of the BETTER farm beef programme. He runs a spring-calving, weanling-producing enterprise on a single 34ha block near Bailieborough in Co Cavan.

Thirty-five cows calved on the farm in 2016, though Garreth is pushing this to 45 for 2017 and is currently in the middle of his breeding season. Breeding starts On 1 April for Garreth – he has traditionally marketed a weanling in the autumn sales and thus calved early by design to maximise sale weight.

“I can make January calving work here – there are just enough housing facilities to get me by and I have a six-bay, well-ventilated cubicle shed, half of which can be turned into a creep area for calves quite easily,” Garreth said. “Going forward, I’d like to move toward finishing my cattle – it seems to be the most profitable way.”

Breeding on the farm involves six weeks of AI and a further six weeks of clean-up bulls. A former dairy farm, the land is set up well for AI breeding – most paddocks have direct access to farm roadways.

As of Tuesday, Garreth had served 38 cows in 32 days, with four repeats – impressive submission given his early calving date and what has been a difficult spring for some around the country.

Getting good nutrition into cows in the weeks prior to breeding is crucial for optimising fertility. Ideally, this nutrition is in the form of grazed grass and for someone breeding as early as Garreth, it has not been plain sailing in 2017.

Early grass

“I am very conscious of having grass for fresh-calvers in the spring and they go to my silage ground first which I purposefully have close to the yard. It means closing up ground early in the back-end but it is worth a lot to me to be able to get cattle out here after calving. They get a couple of days in a nursery paddock behind the shed and then go grazing.

“In terms of ground conditions, it would be one of the better fields on the farm. That said, I had to bring cows and calves in a couple of times when things got bad in the spring. I was glad to have the cubicle shed with the creep area – we had no health issues with calves when they did have to come in, which was great. They were never in for more than two days at a time,” Garreth said.

There is no denying that an AI policy increases the breeding season workload dramatically. Fertility is the cornerstone of successful suckler beef and our attention to detail must be such that we match a theoretical stock bull in terms of conception rates when all is said and done.

Workload

As well as suckling, Garreth works a 48-hour week in a local co-op. He works in shifts, with six days on and two days off. Impressively, despite his off-farm responsibility, his herd is humming in terms of reproductive performance:

Calving interval: 371 days.Calves/cow/year: 0.95.Females not calved in period: 0%.“Look, the AI is very time-consuming when I’m working too. But I think it’s great for the farm, suits the farm and I enjoy it too. I’m getting the best genetics into my cow herd and using terminal sires that sell well in the mart. I know I’m lucky with the layout of the farm in that it facilitates easy rounding-up of cows,” he said.

Garreth’s suckler herd has an average replacement index value of €115, placing him well inside the top 10% of Irish suckler herds in this regard. Going further, his average cow has a carcase weight index value of 17kg (four star), an average milk figure of 5.1kg (five star) and a daughter calving interval figure of -2.19 days (five star).

If Garreth is to finish his progeny in the future, it is vital that he has a cow model that will consistently leave him with a heavy weanling at the year’s end and judging by the herd’s physical performance and genetic breakdown, he is on the right track.

Sires

The Saler breed dominates Garreth’s cow herd, with most cows crossed to Limousin, though there are smatterings of Simmental, Charolais, dairy and Hereford genetics in the group too.

“The Saler has calving and mothering ability. I have not got the luxury of having time to pull every calf, nor can I afford to help dopey calves find their first drink. Obviously the breed has a reputation of being flighty, but I have avoided these types and as you can see the herd is largely quiet,” Garreth remarked, as we stood among a group of cows barely taking notice of us.

This year, Garreth has leaned toward dual-purpose Limousin sires like Castleview Casino (CWI – five star maternal and five star terminal) and Castleview Gazelle (ZAG – five star maternal and four star terminal) with a view to producing both future cows and animals that will perform in the sales ring. Sticking with Saler, he has also used some Ulsan (SA2189), the second-highest indexed (maternal) AI sire currently available, and Doudou (S1544).

I asked Garreth how he copes with rounding up cows to serve and heat detection.

Getting them in

“I think it’s important to have patience. I’m a one-man show here, so I need to keep things as straightforward as possible. That means working with the cows and not getting excited. I use a handheld reel, which I electrify, and a couple of posts to make a funnel towards the gate of a paddock. I loop around the bulling cow slowly and walk her towards the gate. Obviously, I try to bring a cow’s calf with her but if he doesn’t come it’s no issue. I always bring a mate with the cow though.

“If I see a cow bulling at night and I have work the next morning, I’ll bring her in that night and leave her in the shed. I’ve often left a cow in the shed with her calf back in the field and both were fine.

“This year the scratchcard-style tail patches are my principal detection aid and they’re working well. The big periods for detecting heat are between 6am and 8am and after 8pm. I find though if I’m around during the day I often get the odd one in late afternoon.

“I used a teaser bull up until last year but this year he’s gone and I am running everything in one group, including heifers. This way there is lots of activity when animals are in heat.”

On 25 April, Garreth’s eight heifers for breeding averaged 410kg as a group, with the lightest being 385kg. We aim to breed suckler heifers at approximately 400kg – 60% of their mature body weight.

“I have no problem letting my heifers calve near the middle of my calving spread. To be honest, I find that the heifers calving slightly later rarely slip back, probably because they can get to grass quickly after calving and are under less pressure,” Garreth said.

Garreth McCormack is Cavan’s representative in phase three of the BETTER farm beef programme. He runs a spring-calving, weanling-producing enterprise on a single 34ha block near Bailieborough in Co Cavan.

Thirty-five cows calved on the farm in 2016, though Garreth is pushing this to 45 for 2017 and is currently in the middle of his breeding season. Breeding starts On 1 April for Garreth – he has traditionally marketed a weanling in the autumn sales and thus calved early by design to maximise sale weight.

“I can make January calving work here – there are just enough housing facilities to get me by and I have a six-bay, well-ventilated cubicle shed, half of which can be turned into a creep area for calves quite easily,” Garreth said. “Going forward, I’d like to move toward finishing my cattle – it seems to be the most profitable way.”

Breeding on the farm involves six weeks of AI and a further six weeks of clean-up bulls. A former dairy farm, the land is set up well for AI breeding – most paddocks have direct access to farm roadways.

As of Tuesday, Garreth had served 38 cows in 32 days, with four repeats – impressive submission given his early calving date and what has been a difficult spring for some around the country.

Getting good nutrition into cows in the weeks prior to breeding is crucial for optimising fertility. Ideally, this nutrition is in the form of grazed grass and for someone breeding as early as Garreth, it has not been plain sailing in 2017.

Early grass

“I am very conscious of having grass for fresh-calvers in the spring and they go to my silage ground first which I purposefully have close to the yard. It means closing up ground early in the back-end but it is worth a lot to me to be able to get cattle out here after calving. They get a couple of days in a nursery paddock behind the shed and then go grazing.

“In terms of ground conditions, it would be one of the better fields on the farm. That said, I had to bring cows and calves in a couple of times when things got bad in the spring. I was glad to have the cubicle shed with the creep area – we had no health issues with calves when they did have to come in, which was great. They were never in for more than two days at a time,” Garreth said.

There is no denying that an AI policy increases the breeding season workload dramatically. Fertility is the cornerstone of successful suckler beef and our attention to detail must be such that we match a theoretical stock bull in terms of conception rates when all is said and done.

Workload

As well as suckling, Garreth works a 48-hour week in a local co-op. He works in shifts, with six days on and two days off. Impressively, despite his off-farm responsibility, his herd is humming in terms of reproductive performance:

Calving interval: 371 days.Calves/cow/year: 0.95.Females not calved in period: 0%.“Look, the AI is very time-consuming when I’m working too. But I think it’s great for the farm, suits the farm and I enjoy it too. I’m getting the best genetics into my cow herd and using terminal sires that sell well in the mart. I know I’m lucky with the layout of the farm in that it facilitates easy rounding-up of cows,” he said.

Garreth’s suckler herd has an average replacement index value of €115, placing him well inside the top 10% of Irish suckler herds in this regard. Going further, his average cow has a carcase weight index value of 17kg (four star), an average milk figure of 5.1kg (five star) and a daughter calving interval figure of -2.19 days (five star).

If Garreth is to finish his progeny in the future, it is vital that he has a cow model that will consistently leave him with a heavy weanling at the year’s end and judging by the herd’s physical performance and genetic breakdown, he is on the right track.

Sires

The Saler breed dominates Garreth’s cow herd, with most cows crossed to Limousin, though there are smatterings of Simmental, Charolais, dairy and Hereford genetics in the group too.

“The Saler has calving and mothering ability. I have not got the luxury of having time to pull every calf, nor can I afford to help dopey calves find their first drink. Obviously the breed has a reputation of being flighty, but I have avoided these types and as you can see the herd is largely quiet,” Garreth remarked, as we stood among a group of cows barely taking notice of us.

This year, Garreth has leaned toward dual-purpose Limousin sires like Castleview Casino (CWI – five star maternal and five star terminal) and Castleview Gazelle (ZAG – five star maternal and four star terminal) with a view to producing both future cows and animals that will perform in the sales ring. Sticking with Saler, he has also used some Ulsan (SA2189), the second-highest indexed (maternal) AI sire currently available, and Doudou (S1544).

I asked Garreth how he copes with rounding up cows to serve and heat detection.

Getting them in

“I think it’s important to have patience. I’m a one-man show here, so I need to keep things as straightforward as possible. That means working with the cows and not getting excited. I use a handheld reel, which I electrify, and a couple of posts to make a funnel towards the gate of a paddock. I loop around the bulling cow slowly and walk her towards the gate. Obviously, I try to bring a cow’s calf with her but if he doesn’t come it’s no issue. I always bring a mate with the cow though.

“If I see a cow bulling at night and I have work the next morning, I’ll bring her in that night and leave her in the shed. I’ve often left a cow in the shed with her calf back in the field and both were fine.

“This year the scratchcard-style tail patches are my principal detection aid and they’re working well. The big periods for detecting heat are between 6am and 8am and after 8pm. I find though if I’m around during the day I often get the odd one in late afternoon.

“I used a teaser bull up until last year but this year he’s gone and I am running everything in one group, including heifers. This way there is lots of activity when animals are in heat.”

On 25 April, Garreth’s eight heifers for breeding averaged 410kg as a group, with the lightest being 385kg. We aim to breed suckler heifers at approximately 400kg – 60% of their mature body weight.

“I have no problem letting my heifers calve near the middle of my calving spread. To be honest, I find that the heifers calving slightly later rarely slip back, probably because they can get to grass quickly after calving and are under less pressure,” Garreth said.

SHARING OPTIONS