In the Budget last October the Government announced a review of farm taxation was to be undertaken. Taxation could have a huge influence on dairy expansion post-2015 and the potential of the Irish dairy industry to achieve the Government’s Food Harvest 2020 targets.

Two of the biggest challenges facing dairy farms are cashflow and milk price volatility. A tax strategy which would help expanding dairy farms cope with these challenges would reduce risk and deliver huge benefits to farmers. The positive effect profitable expansion would have on the country’s economy would be a big bonus for the Government.

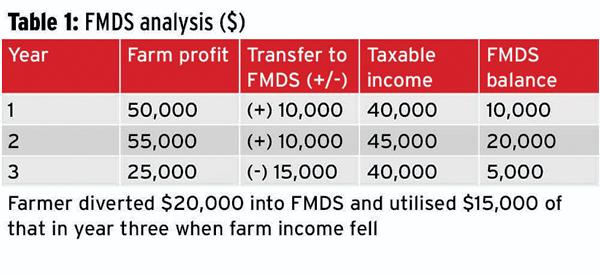

In Australia, the government implemented a scheme called the Farm Management Deposit Scheme (FMDS) which helps farmers deal with risk. When farmers have a good financial year, they can set aside part of their pre-tax farm income into a special account (Table 1). The income is not taxed until the year it is drawn back down and it can earn interest while it is deposited. Banks, credit unions and building societies manage these accounts, offering different interest rates.

The FMDS encourages tax-efficient, smart saving. Tax is still inevitably paid on all income but income that would be exposed to a high tax bill is deposited and made active again when required.

As important as tax saving is that the farm has a reserve of income that can be accessed in a poor financial year. Farmers can also choose to draw down the income in a year where they are carrying out farm development.

The FMDS was first set up in 1999. Australia has 6,300 dairy farmers and stats from the FMDS show that there are 3,000 accounts held by dairy farmers with an average amount per account of $68,000 (€43,000). Farmers can have multiple accounts but the maximum any farmer can hold in the FMDS is $400,000 (€252,000). The scheme is open to all types of primary agricultural activity – beef, sheep, tillage, horticulture, etc.

The Australian government made the scheme available to farmers to give them the opportunity to control risk, as opposed to having to engage in crisis management when businesses were put under financial pressure. The government was particularly worried about the fluctuation in weather trends and global price volatility.

Putting money away in a good year in preparation for a bad year is a strategy that will be crucial for all Irish dairy farms to cope with milk price volatility. For those planning on milking more cows when quotas go, it could be the difference between success and failure. However, the key issue highlighted by farmers when putting away money is that it is difficult to build after-tax cash reserves.

Dairy expansion promises much potential for Irish dairy farmers – and the whole Irish economy – but fluctuation in weather (as in 2009 and 2012) and milk price volatility will pose serious challenges. Could a similar Government scheme in Ireland provide farmers with the opportunity to protect themselves from these risks?

In a high-income year, a farmer facing a high tax bill in Ireland is currently encouraged to spend liberally to reduce his/her tax exposure, often on items which deliver a poor return on investment. The opportunity to instead put this money aside to be drawn down when really needed could act as a huge safety net to fall back on when milk price drops. Repayments on investments for expansion must be paid regardless of milk price so having cash put aside is essential.

Qualification

In Australia, companies can’t access the FMDS. As in Ireland, companies pay the same rate of tax regardless of total profit. The scheme is available to sole traders and individuals in a farm partnership.

To be in a position to put money into a government account, the farm business has to be profitable and have cash to deposit.

For this reason, the scheme will tend to suit larger farms where, after drawings, there is still income to be deposited. Exposure to the higher rate of tax will also tend to be greater on larger farms. In a year of high milk prices, dairy farms of all scales could make use of the scheme.

The requirements to take part in the FMDS in Australia are:

You must deposit $1,000 or more each time. The scheme requires funds to be deposited for at least 12 months with a deposit-taking institution (bank, credit union or building society). There is a minimum 12-month deposit period. This can be set aside if the government decides exceptional circumstances have occurred which mean farmers need immediate access to saved cash, eg during a severe drought.Farmers can hold multiple accounts with different financial entities but the maximum total which can be held in the scheme is $400,000.Off-farm income is capped at $65,000 (€41,000) per year.Companies don’t qualify to use the scheme.Options

What volatility management options are currently available for Irish farmers and why would a scheme such as Australia’s be better?

Income averaging is one option which has actually led to farmers being exposed to a higher tax bill in a poor income year. For example, in 2009 milk price fell to 23c/l, meaning incomes and profits were drastically reduced. However, a farmer using income averaging had to pay the average tax based on 2007, 2008 (both good milk price years) and 2009, which was much higher than what the actual 2009 tax bill would have been on its own.

If a scheme such as the Australian one was in place, farmers would have had money in the scheme after two relatively good years, which they could have drawn down in 2009.

Fixing a price for part of your milk supply is currently an option with a small number of processors to insulate against drops in milk price but it is then also insulated against rises in milk price – as seen this year. It also costs farmers and co-ops to get a fixed milk price contract with a hedging company.

In Ireland, an FMDS could protect dairy (and other) farms from price volatility and lead to more planned expenditure and investment. In Australia, farmers can access money within the 12-month time frame due to exceptional circumstances if needed. A comparison could be spring 2013 in Ireland where the Government could have granted full access to any income deposited under the FMDS in 2012 to allow farmers purchase fodder.

Proving popular

The Australian government has actually made changes to the FMDS to make it more appealing for farmers. Originally the cap on how much a farmer could hold was $300,000 (since increased to $400,000) and the threshold for maximum off-farm income has been increased from $50,000 to $65,000.

There is also the option of transferring money from the FMDS to a superannuation fund, allowing farmers to prepare for retirement.

An innovative tax scheme such as this would deliver much-needed support to commercial farmers who want to realise the potential that quota removal has for Irish farms.

Stock

relief policy

In Ireland, current farm taxation policy on stock relief is likely to pose significant challenges for farmers hoping to expand. Rearing extra dairy replacements to increase herd size puts a significant strain on cashflow due to higher rearing costs, while stock sales are reduced as animals are held in the herd to help increase numbers. This is a severe enough challenge but is added to as the growth in livestock within the herd is viewed as income and therefore liable to tax.

The farmer is investing money in stock for the future and paying increased tax on these stock that, as of yet, are producing little or no output. Add this to investing in grazing infrastructure, reseeding, winter housing and milking facilities for extra stock and you have a business under potentially severe financial pressure.

Current stock relief of 25% for farmers will offer very little protection from increased tax bills. Stock relief for young farmers has been limited to a total of €70,000 in a farmer’s first four years, which was previously uncapped.

When Ireland last went through a period of significant dairy expansion in the 1970s, all farms could access stock relief. Surely the case could be made that again offering 100% stock relief for farms in expansion is more in the long-term interest of Government rather than imposing tax on these stock before they begin producing any milk?

The potential benefits of expansion are huge at both farmer level from increased profits and economy level with increased levels of employment, exports and industry activity. However, the realities of achieving these benefits while coping with milk price volatility, weather fluctuation, loan repayments, etc, are also formidable.

Changes to farm taxation policies could help farmers achieve the potential and realise the benefits of expansion for themselves and the economy.

In the Budget last October the Government announced a review of farm taxation was to be undertaken. Taxation could have a huge influence on dairy expansion post-2015 and the potential of the Irish dairy industry to achieve the Government’s Food Harvest 2020 targets.

Two of the biggest challenges facing dairy farms are cashflow and milk price volatility. A tax strategy which would help expanding dairy farms cope with these challenges would reduce risk and deliver huge benefits to farmers. The positive effect profitable expansion would have on the country’s economy would be a big bonus for the Government.

In Australia, the government implemented a scheme called the Farm Management Deposit Scheme (FMDS) which helps farmers deal with risk. When farmers have a good financial year, they can set aside part of their pre-tax farm income into a special account (Table 1). The income is not taxed until the year it is drawn back down and it can earn interest while it is deposited. Banks, credit unions and building societies manage these accounts, offering different interest rates.

The FMDS encourages tax-efficient, smart saving. Tax is still inevitably paid on all income but income that would be exposed to a high tax bill is deposited and made active again when required.

As important as tax saving is that the farm has a reserve of income that can be accessed in a poor financial year. Farmers can also choose to draw down the income in a year where they are carrying out farm development.

The FMDS was first set up in 1999. Australia has 6,300 dairy farmers and stats from the FMDS show that there are 3,000 accounts held by dairy farmers with an average amount per account of $68,000 (€43,000). Farmers can have multiple accounts but the maximum any farmer can hold in the FMDS is $400,000 (€252,000). The scheme is open to all types of primary agricultural activity – beef, sheep, tillage, horticulture, etc.

The Australian government made the scheme available to farmers to give them the opportunity to control risk, as opposed to having to engage in crisis management when businesses were put under financial pressure. The government was particularly worried about the fluctuation in weather trends and global price volatility.

Putting money away in a good year in preparation for a bad year is a strategy that will be crucial for all Irish dairy farms to cope with milk price volatility. For those planning on milking more cows when quotas go, it could be the difference between success and failure. However, the key issue highlighted by farmers when putting away money is that it is difficult to build after-tax cash reserves.

Dairy expansion promises much potential for Irish dairy farmers – and the whole Irish economy – but fluctuation in weather (as in 2009 and 2012) and milk price volatility will pose serious challenges. Could a similar Government scheme in Ireland provide farmers with the opportunity to protect themselves from these risks?

In a high-income year, a farmer facing a high tax bill in Ireland is currently encouraged to spend liberally to reduce his/her tax exposure, often on items which deliver a poor return on investment. The opportunity to instead put this money aside to be drawn down when really needed could act as a huge safety net to fall back on when milk price drops. Repayments on investments for expansion must be paid regardless of milk price so having cash put aside is essential.

Qualification

In Australia, companies can’t access the FMDS. As in Ireland, companies pay the same rate of tax regardless of total profit. The scheme is available to sole traders and individuals in a farm partnership.

To be in a position to put money into a government account, the farm business has to be profitable and have cash to deposit.

For this reason, the scheme will tend to suit larger farms where, after drawings, there is still income to be deposited. Exposure to the higher rate of tax will also tend to be greater on larger farms. In a year of high milk prices, dairy farms of all scales could make use of the scheme.

The requirements to take part in the FMDS in Australia are:

You must deposit $1,000 or more each time. The scheme requires funds to be deposited for at least 12 months with a deposit-taking institution (bank, credit union or building society). There is a minimum 12-month deposit period. This can be set aside if the government decides exceptional circumstances have occurred which mean farmers need immediate access to saved cash, eg during a severe drought.Farmers can hold multiple accounts with different financial entities but the maximum total which can be held in the scheme is $400,000.Off-farm income is capped at $65,000 (€41,000) per year.Companies don’t qualify to use the scheme.Options

What volatility management options are currently available for Irish farmers and why would a scheme such as Australia’s be better?

Income averaging is one option which has actually led to farmers being exposed to a higher tax bill in a poor income year. For example, in 2009 milk price fell to 23c/l, meaning incomes and profits were drastically reduced. However, a farmer using income averaging had to pay the average tax based on 2007, 2008 (both good milk price years) and 2009, which was much higher than what the actual 2009 tax bill would have been on its own.

If a scheme such as the Australian one was in place, farmers would have had money in the scheme after two relatively good years, which they could have drawn down in 2009.

Fixing a price for part of your milk supply is currently an option with a small number of processors to insulate against drops in milk price but it is then also insulated against rises in milk price – as seen this year. It also costs farmers and co-ops to get a fixed milk price contract with a hedging company.

In Ireland, an FMDS could protect dairy (and other) farms from price volatility and lead to more planned expenditure and investment. In Australia, farmers can access money within the 12-month time frame due to exceptional circumstances if needed. A comparison could be spring 2013 in Ireland where the Government could have granted full access to any income deposited under the FMDS in 2012 to allow farmers purchase fodder.

Proving popular

The Australian government has actually made changes to the FMDS to make it more appealing for farmers. Originally the cap on how much a farmer could hold was $300,000 (since increased to $400,000) and the threshold for maximum off-farm income has been increased from $50,000 to $65,000.

There is also the option of transferring money from the FMDS to a superannuation fund, allowing farmers to prepare for retirement.

An innovative tax scheme such as this would deliver much-needed support to commercial farmers who want to realise the potential that quota removal has for Irish farms.

Stock

relief policy

In Ireland, current farm taxation policy on stock relief is likely to pose significant challenges for farmers hoping to expand. Rearing extra dairy replacements to increase herd size puts a significant strain on cashflow due to higher rearing costs, while stock sales are reduced as animals are held in the herd to help increase numbers. This is a severe enough challenge but is added to as the growth in livestock within the herd is viewed as income and therefore liable to tax.

The farmer is investing money in stock for the future and paying increased tax on these stock that, as of yet, are producing little or no output. Add this to investing in grazing infrastructure, reseeding, winter housing and milking facilities for extra stock and you have a business under potentially severe financial pressure.

Current stock relief of 25% for farmers will offer very little protection from increased tax bills. Stock relief for young farmers has been limited to a total of €70,000 in a farmer’s first four years, which was previously uncapped.

When Ireland last went through a period of significant dairy expansion in the 1970s, all farms could access stock relief. Surely the case could be made that again offering 100% stock relief for farms in expansion is more in the long-term interest of Government rather than imposing tax on these stock before they begin producing any milk?

The potential benefits of expansion are huge at both farmer level from increased profits and economy level with increased levels of employment, exports and industry activity. However, the realities of achieving these benefits while coping with milk price volatility, weather fluctuation, loan repayments, etc, are also formidable.

Changes to farm taxation policies could help farmers achieve the potential and realise the benefits of expansion for themselves and the economy.

SHARING OPTIONS