The abomasum is the fourth stomach of ruminants such as cattle. It normally lies on the floor of the abdomen. However, particularly in dairy cows post-calving, it can become displaced. This displacement can occur either to the left (LDA) or right (RDA) of the abdomen, where it tends to rise up under the ribs due to distension with gas, this can lead to poor appetite and reduced milk yield in the periparturient (the period from two weeks before to four weeks after calving) dairy cow.

Causes

There are a number of common risk factors for displacement of the abomasum. Cows which are overconditioned at calving (body condition score =3.5) are particularly at risk.

Other factors which can lead to a displaced abomasum include:

Subclinical or clinical hypocalcaemia / milk fever (low blood calcium).Excess concentrates in relation to forage in the diet of the cow post-calving, resulting in the production of large volumes of volatile fatty acids in the abomasums.A lack of long fibre in the diet. A poor transition diet in the immediate post-calving period, ie too much concentrates introduced too quickly into the diet. Concurrent disease, eg retained placenta, metritis etc. Large calves or twins leading to lots of space for movement of the abomasum after calving. Negative energy balance (ketosis) in the periparturient period.Social and metabolic stress in first-lactation cows, particularly when feed barrier space is restricted.Beef breeds occasionally develop right displacement and volvulus - RDV (this is displacement with concurrent twisting) of the abomasum. It can usually occur in beef animals fed diets with an imbalance between concentrates and forage/fibre.

Symptoms

The classic symptoms of this condition are of a marked drop in milk production in a recently calved dairy cow. Cows tend to stop eating concentrates while continuing to eat forage (hay, silage, maize or grass), although it tends to be at a reduced rate.

This selective consumption of fodder occurs because all of these cows develop secondary ketosis, ie they are breaking down fat off their back as an energy source. This is to compensate for the fact that digested food substrates are not being absorbed from the rumen or passing down to the intestines for absorption.

The physical displacement of the abomasum and its dilation with gas is painful and leads to reduced motility of all the cows’ stomachs. The cow will quickly lose body condition and look empty due to lack of rumen fill.

In some cows with LDA, the last three ribs on the left flank may be sprung outwards. If there is an RVA, ie displacement and simultaneous twisting of the stomach high on the right flank, cows will become very sick in the space of hours. They will develop signs of shock with sunken eyes, weakness, depression and distension of the abdomen as fluid builds up within the twisted abomasum. While LDA is not an immediately life-threatening condition, RVA leads to death in 12 to 24 hours.

Treatment

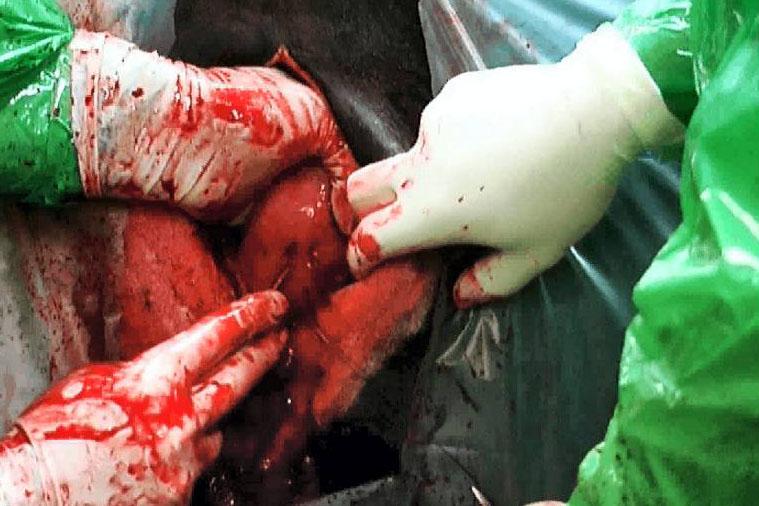

Displaced abomasum can be managed conservatively but is best treated using surgical correction. Conservative management includes techniques such as rolling the cow, altering the diet and treating concurrent disease, but failure and recurrence rates are quite high. Surgical correction is very successful for LDA and has a high cost-benefit ratio – there is an economic benefit in favour of surgical intervention. The prognosis for RDAs does not tend to be as good. In the case of RVA, the prognosis is poor and very few affected cows survive RVAs.

Prevention and control

Displacement of the abomasum can be prevented by minimising the known risk factors. In particular, attention should be given to body condition scoring of dry cows to ensure that they calve down at BCS 3-3.25. Introducing small quantities of concentrates in late pregnancy in the transition period can make a very significant difference. The addition of long fibre to the dry cow and milking cow diets can also aid in prevention of the condition. Also feeding of good quality dry cow minerals with adequate magnesium is one of the best preventative measures for hypocalcaemia.

The abomasum is the fourth stomach of ruminants such as cattle. It normally lies on the floor of the abdomen. However, particularly in dairy cows post-calving, it can become displaced. This displacement can occur either to the left (LDA) or right (RDA) of the abdomen, where it tends to rise up under the ribs due to distension with gas, this can lead to poor appetite and reduced milk yield in the periparturient (the period from two weeks before to four weeks after calving) dairy cow.

Causes

There are a number of common risk factors for displacement of the abomasum. Cows which are overconditioned at calving (body condition score =3.5) are particularly at risk.

Other factors which can lead to a displaced abomasum include:

Subclinical or clinical hypocalcaemia / milk fever (low blood calcium).Excess concentrates in relation to forage in the diet of the cow post-calving, resulting in the production of large volumes of volatile fatty acids in the abomasums.A lack of long fibre in the diet. A poor transition diet in the immediate post-calving period, ie too much concentrates introduced too quickly into the diet. Concurrent disease, eg retained placenta, metritis etc. Large calves or twins leading to lots of space for movement of the abomasum after calving. Negative energy balance (ketosis) in the periparturient period.Social and metabolic stress in first-lactation cows, particularly when feed barrier space is restricted.Beef breeds occasionally develop right displacement and volvulus - RDV (this is displacement with concurrent twisting) of the abomasum. It can usually occur in beef animals fed diets with an imbalance between concentrates and forage/fibre.

Symptoms

The classic symptoms of this condition are of a marked drop in milk production in a recently calved dairy cow. Cows tend to stop eating concentrates while continuing to eat forage (hay, silage, maize or grass), although it tends to be at a reduced rate.

This selective consumption of fodder occurs because all of these cows develop secondary ketosis, ie they are breaking down fat off their back as an energy source. This is to compensate for the fact that digested food substrates are not being absorbed from the rumen or passing down to the intestines for absorption.

The physical displacement of the abomasum and its dilation with gas is painful and leads to reduced motility of all the cows’ stomachs. The cow will quickly lose body condition and look empty due to lack of rumen fill.

In some cows with LDA, the last three ribs on the left flank may be sprung outwards. If there is an RVA, ie displacement and simultaneous twisting of the stomach high on the right flank, cows will become very sick in the space of hours. They will develop signs of shock with sunken eyes, weakness, depression and distension of the abdomen as fluid builds up within the twisted abomasum. While LDA is not an immediately life-threatening condition, RVA leads to death in 12 to 24 hours.

Treatment

Displaced abomasum can be managed conservatively but is best treated using surgical correction. Conservative management includes techniques such as rolling the cow, altering the diet and treating concurrent disease, but failure and recurrence rates are quite high. Surgical correction is very successful for LDA and has a high cost-benefit ratio – there is an economic benefit in favour of surgical intervention. The prognosis for RDAs does not tend to be as good. In the case of RVA, the prognosis is poor and very few affected cows survive RVAs.

Prevention and control

Displacement of the abomasum can be prevented by minimising the known risk factors. In particular, attention should be given to body condition scoring of dry cows to ensure that they calve down at BCS 3-3.25. Introducing small quantities of concentrates in late pregnancy in the transition period can make a very significant difference. The addition of long fibre to the dry cow and milking cow diets can also aid in prevention of the condition. Also feeding of good quality dry cow minerals with adequate magnesium is one of the best preventative measures for hypocalcaemia.

SHARING OPTIONS