Elizabeth Thompson, Lady Butler (1846-1933) was a British painter who specialised in painting scenes from military campaigns, including the Crimean and Napoleonic Wars.

Her work was enormously popular in her early life – a period when Victorian pride in the growing British Empire was at its highest.

Elizabeth began receiving art instruction in 1862 while growing up in Italy. In 1866, she entered the Royal Female School of Art in South Kensington, London, and began exhibiting her artwork (usually watercolours) as a student.

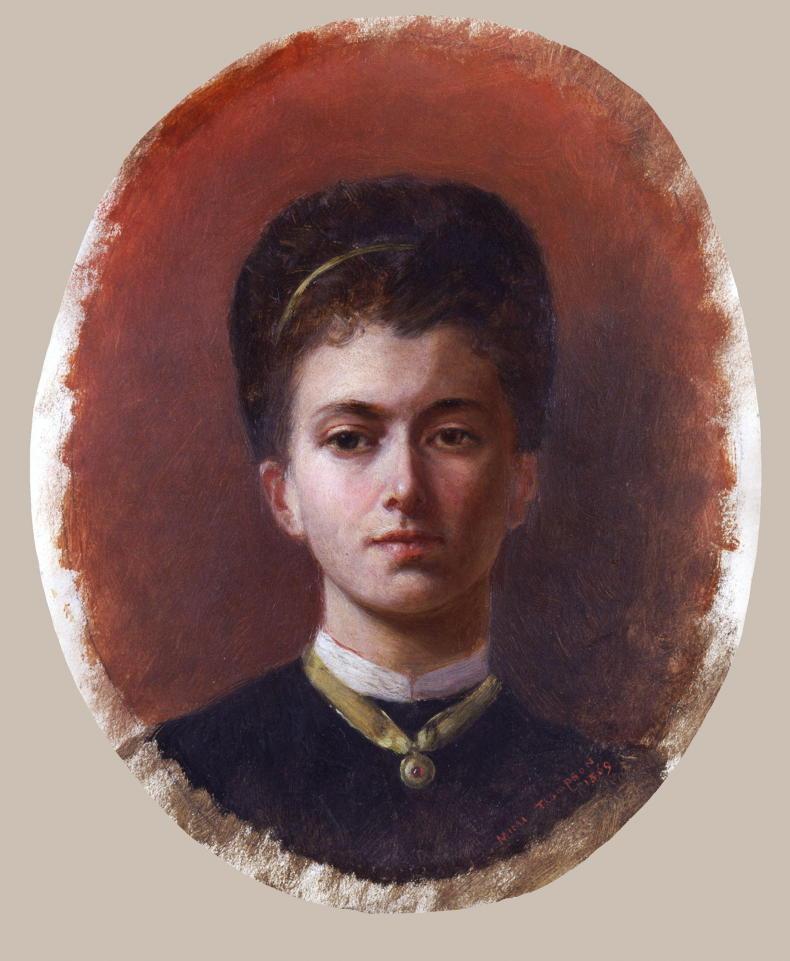

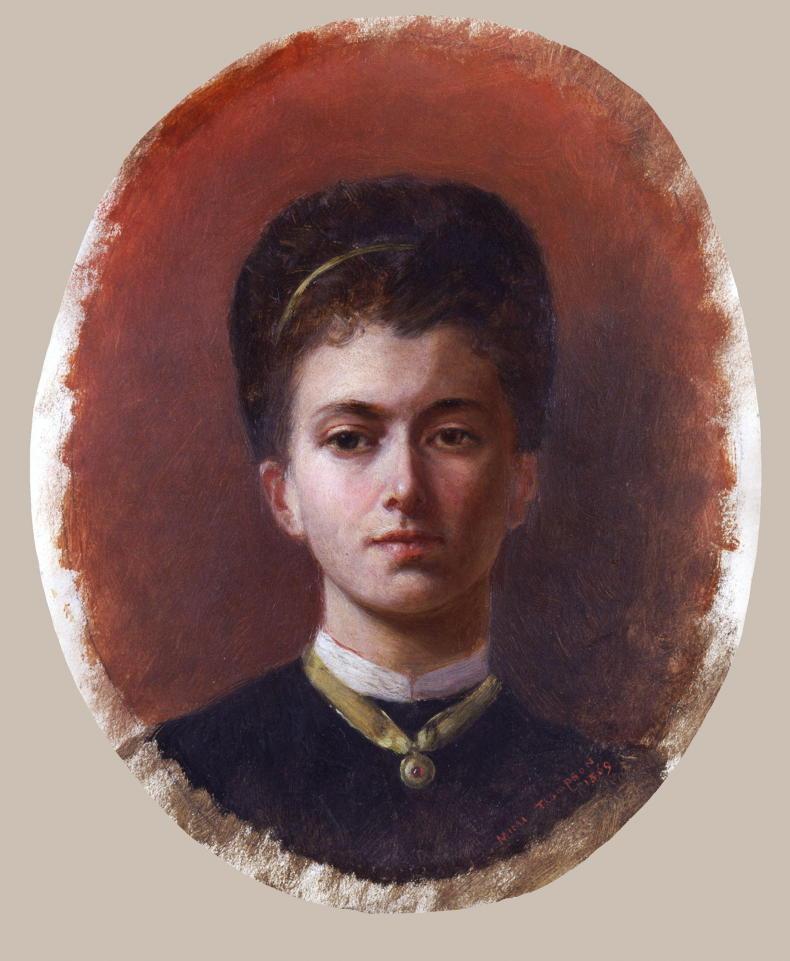

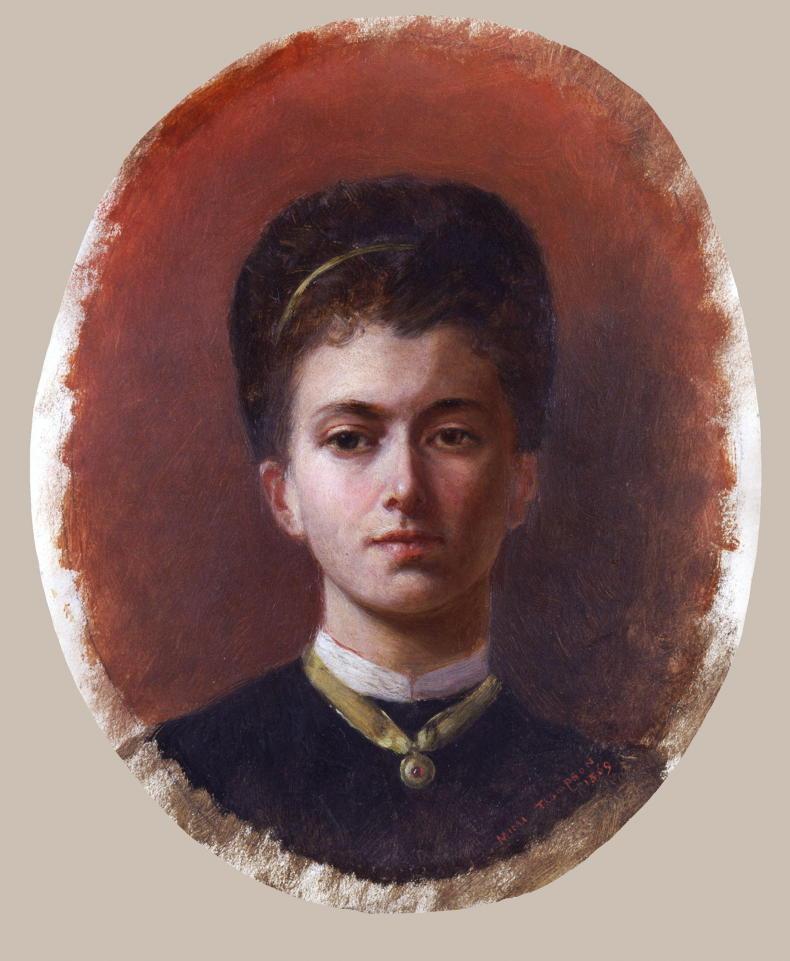

Elizabeth Southerden Butler (self portrait).

She created a sensation in 1874 when, at the age of 27, her sombre, evocative Crimean War scene The Roll Call was accepted and displayed by the Royal Academy. The painting was purchased by Queen Victoria and was not only a critical sensation but a public one as well.

In 1877 she married William Francis Butler, an officer of the British Army who had grown up in Golden, Co Tipperary. Much of the Butler family’s wealth had been dissipated over the years in fines and confiscations resulting from the family’s refusal to give up the Catholic faith.

Many people looked askance at the match between the Jesuit-educated, Irish Catholic soldier with the decidedly left-leaning outlook and quintessentially English toast of the London art scene.

Her 1890 painting Evicted was the result of Elizabeth witnessing the eviction of an Irish woman from her cottage in the Wicklow mountains

Notwithstanding his distinguished military career, which saw him reach the rank of Lieutenant General and a knighthood, William Butler was known as a proponent of Irish Home Rule and an admirer of Charles Stewart Parnell. Over time, his wife was to take on a good deal of his political shading.

Her 1890 painting Evicted was the result of Elizabeth witnessing the eviction of an Irish woman from her cottage in the Wicklow mountains. When it was exhibited in London, it was met with disapproval for being “too political”. The British establishment of the time did not appreciate open criticism of the Empire from one of their own.

The earlier Listed for the Connaught Rangers is a more ambiguous work. Elizabeth came to Ireland for the first time in 1877 on her honeymoon and grew to love the country and its people. She described Connaught Rangers as her first married painting and she sketched it in Kerry, where she also found her models for the two recruits. The painting shows two Irishmen marching down a glen with a red-jacketed recruiting party; bound for service in the famous 88th Regiment of Foot (Connaught Rangers), who served with distinction from South Africa to the Somme for 135 years.

Elizabeth may have intended that Connaught Rangers would draw attention to the economic plight that forced Ireland’s youth into the army of its ancient ruler

One of the young recruits is looking straight ahead, head up, shoulders back, hands in pockets and clay pipe in mouth as he marches off to meet a future far beyond the confines of the misty west of Ireland. The other, by contrast, throws a rueful backward glance at a ruined cabin, perhaps the home he had to leave.

Elizabeth may have intended that Connaught Rangers would draw attention to the economic plight that forced Ireland’s youth into the army of its ancient ruler. However, when the painting was exhibited at London’s Royal Academy in 1879, most British commentators chose to view it as a tribute to a country that – despite its social problems – could still send loyal young men to fight the Empire’s wars.

Elizabeth Butler travelled to the far reaches of the Empire on her husband’s various postings until the couple retired to Bansha Castle in 1905. She spent the final years of her life with her daughter Eileen, Viscountess Gormanston, at Gormanston Castle, Co Meath. She died there shortly before her 87th birthday and is buried at nearby Stamullen graveyard.

Elizabeth Thompson, Lady Butler (1846-1933) was a British painter who specialised in painting scenes from military campaigns, including the Crimean and Napoleonic Wars.

Her work was enormously popular in her early life – a period when Victorian pride in the growing British Empire was at its highest.

Elizabeth began receiving art instruction in 1862 while growing up in Italy. In 1866, she entered the Royal Female School of Art in South Kensington, London, and began exhibiting her artwork (usually watercolours) as a student.

Elizabeth Southerden Butler (self portrait).

She created a sensation in 1874 when, at the age of 27, her sombre, evocative Crimean War scene The Roll Call was accepted and displayed by the Royal Academy. The painting was purchased by Queen Victoria and was not only a critical sensation but a public one as well.

In 1877 she married William Francis Butler, an officer of the British Army who had grown up in Golden, Co Tipperary. Much of the Butler family’s wealth had been dissipated over the years in fines and confiscations resulting from the family’s refusal to give up the Catholic faith.

Many people looked askance at the match between the Jesuit-educated, Irish Catholic soldier with the decidedly left-leaning outlook and quintessentially English toast of the London art scene.

Her 1890 painting Evicted was the result of Elizabeth witnessing the eviction of an Irish woman from her cottage in the Wicklow mountains

Notwithstanding his distinguished military career, which saw him reach the rank of Lieutenant General and a knighthood, William Butler was known as a proponent of Irish Home Rule and an admirer of Charles Stewart Parnell. Over time, his wife was to take on a good deal of his political shading.

Her 1890 painting Evicted was the result of Elizabeth witnessing the eviction of an Irish woman from her cottage in the Wicklow mountains. When it was exhibited in London, it was met with disapproval for being “too political”. The British establishment of the time did not appreciate open criticism of the Empire from one of their own.

The earlier Listed for the Connaught Rangers is a more ambiguous work. Elizabeth came to Ireland for the first time in 1877 on her honeymoon and grew to love the country and its people. She described Connaught Rangers as her first married painting and she sketched it in Kerry, where she also found her models for the two recruits. The painting shows two Irishmen marching down a glen with a red-jacketed recruiting party; bound for service in the famous 88th Regiment of Foot (Connaught Rangers), who served with distinction from South Africa to the Somme for 135 years.

Elizabeth may have intended that Connaught Rangers would draw attention to the economic plight that forced Ireland’s youth into the army of its ancient ruler

One of the young recruits is looking straight ahead, head up, shoulders back, hands in pockets and clay pipe in mouth as he marches off to meet a future far beyond the confines of the misty west of Ireland. The other, by contrast, throws a rueful backward glance at a ruined cabin, perhaps the home he had to leave.

Elizabeth may have intended that Connaught Rangers would draw attention to the economic plight that forced Ireland’s youth into the army of its ancient ruler. However, when the painting was exhibited at London’s Royal Academy in 1879, most British commentators chose to view it as a tribute to a country that – despite its social problems – could still send loyal young men to fight the Empire’s wars.

Elizabeth Butler travelled to the far reaches of the Empire on her husband’s various postings until the couple retired to Bansha Castle in 1905. She spent the final years of her life with her daughter Eileen, Viscountess Gormanston, at Gormanston Castle, Co Meath. She died there shortly before her 87th birthday and is buried at nearby Stamullen graveyard.

SHARING OPTIONS