Eighty years ago this week, the trial of one Henry ‘Harry’ Gleeson commenced. Gleeson was charged with the murder of Mary ‘Moll’ McCarthy – he was found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging.

However, then, as now, many knew that Harry Gleeson was innocent.

In response to great work from the ‘Justice for Harry Gleeson Group’ and ‘The Irish Innocence Project’, in 2015 President Michael D Higgins signed a posthumous pardon for Harry Gleeson, which formally declared his innocence and acknowledged the miscarriage of justice that occurred.

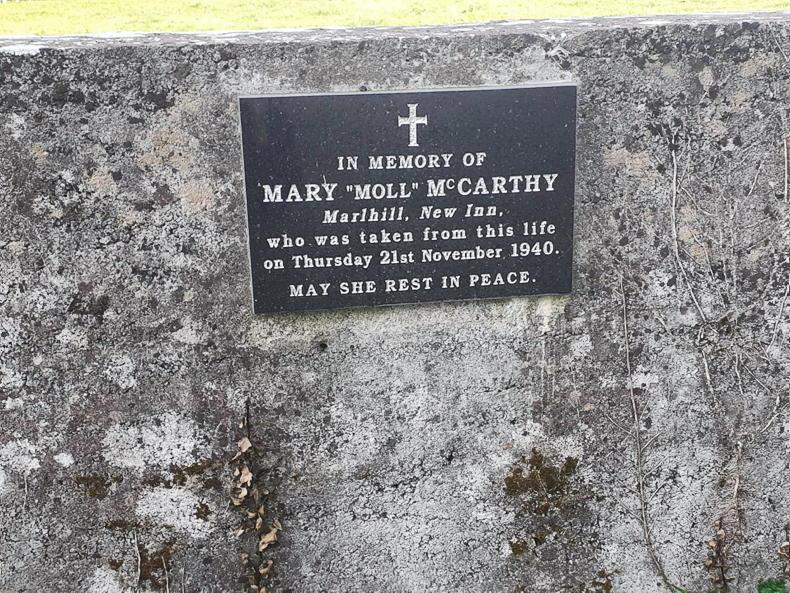

The village of New-Inn in Co Tipperary came to national attention following the events in November 1940, when Moll McCarthy was found murdered in a field owned by a man named John Caesar – the farm was managed by Caesar’s nephew, Harry Gleeson.

Moll McCarthy was born into and lived in very unfortunate circumstances: six children to feed, living in a rundown cottage and relying on “gifts” from the respectable men who fathered her children and took advantage of her vulnerability.

At the time, a local, well-respected vigilante group – most former IRA men – were a law unto themselves. Kieran Fagan published The Framing of Harry Gleeson (2015), which claimed Moll was murdered by this group due to fears she was passing information to the local Garda Sergeant.

A conspiracy of silence surrounded the village of New-Inn, as the local clergy turned a blind eye (and parishioners followed) and the police fabricated evidence in the direction of Gleeson. This local vigilante group viciously took the life of Moll McCarthy – and strategically plotted links of her death back to Gleeson.

If the events there were bad, the events in the courts were equally so. Sean McBride was Harry’s junior counsel and Martin Maguire was the judge.

A year earlier, Maguire – then a prosecutor – was on the losing side to McBride in a massive case. It was a huge win for McBride. With Maguire, now a judge, in charge of Harry’s case, he had ample chance to get one back on McBride.

Throughout the trial, it was noted that Maguire subtly influenced the jury in numerous ways in favour of the prosecution. From the outset, it was a hanging judge - and hence, a hanging jury. In February 1941, Harry was sentenced to death by hanging; a mere three months after the murder occurred.

After a failed appeal, Harry Gleeson’s state execution took place on 23 April 1941.

Harry’s last words (to his barrister, McBride) were poignant:

“The last thing I want to say is that I will pray tomorrow that whoever did it will be discovered and that the whole thing will be like an open book. I rely on you to clear my name. I have no confession to make, only that I didn’t do it. That is all. I will pray for you and be with you if I can, whenever you are fighting and battling for justice.”

Fagan names those he says were responsible for the murder in his book, and all the subsequent characters, from the clergy to the police to the state. All of whom who were in one way or another involved in the murder of Moll McCarthy and the ultimate execution of Harry Gleeson. Still to this day, in New-Inn, there is nothing to formally acknowledge the wrong done to Harry Gleeson, despite the posthumous pardon, the first in the state’s history.

Then, as now, there are honourable exceptions – those who stood for justice – and for Harry Gleeson and Moll McCarthy, and it is to them, the truth is owed.

Despite ongoing work from the Gleeson family and the Department of Justice, Harry Gleeson’s remains still lie in Mountjoy prison grounds – and that of Moll McCarthy lies in an unmarked grave in a disused cemetery in New-Inn.

God rest Harry Gleeson and Moll McCarthy, and Godspeed to all those who fight against the miscarriage of justice.

The above gives a snapshot of events The Murder at Marlhill by Marcus Bourke (1993) and the more recent book The Framing of Harry Gleeson by Kieran Fagan (2015), give brilliant accounts of the full story.

Conor is an amateur historian with a keen interest in local events during 1919-1923; the War of Independence and the Irish Civil War in. He is also a Teagasc Walsh Scholar and PhD researcher in the National Centre for Men’s Health in IT Carlow.

SHARING OPTIONS